- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Guatemala: A Vote for Turning the Tide

GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Guatemala: A Vote for Turning the Tide

Nummer 1 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-3573

In the surprise victory of Bernardo Arévalo in Guatemala’s run-off presidential elections in August 2023, various elements came together: elite miscalculation, broad mobilisation of civil society, and some remnants of the rule of law. In Central America, authoritarianism has been on the rise for two decades now. If Arévalo and his political reform agenda prevail, a turning point could be marked.

Central American countries have seen a significant rolling back of democratic reforms and institutions. Nicaragua is once more a family dictatorship; El Salvador is on its way to electoral authoritarianism. The recent election of reformist Arévalo might be a sign that changing track via elections is indeed possible.

Arévalo faced a bumpy road from election victory on 20 August 2023 to inauguration on 14 January of this year, as corrupt elites weaponised Guatemala’s judicial system, trying to prevent him from taking office and undermining his ability to govern. Their remaining state control and connection to both state and non-state armed actors will also limit the new government’s scope for action.

Significant challenges are looming for the new Guatemalan government. It does not have a majority in Congress and some of Arévalo’s staunchest adversaries, such as Attorney General María Consuelo Porras Argueta, are still in office. Strengthening democratic oversight mechanisms, re-establishing judicial independence, and nurturing an active civil society will be crucial for tackling authoritarian tendencies.

Policy Implications

Democratic-reform actors and civil society rarely control important resources vis-à-vis the state and economy. They face, rather, severe attacks, thus needing the international community’s support. Due to uncertainty about the United States’ future agenda, the European Union must play a more prominent role in revitalising democracy and supporting reformist actors in Guatemala and Central America.

From Hope to Roll Back: Ending Wars, Reversing Democratic Reforms

The surprise election of Bernardo Arévalo in Guatemala’s run-off presidential elections in August 2023 was the combined result of elite miscalculation, a broad mobilisation of civil society, and some remnants of the rule of law. One, the country’s corrupt elites did not foresee his success – otherwise, he would have been excluded from the ballot as many others were. Two, the broad discontent among civil society mobilised an unprecedented number of voters to turn out. Last but not least, third, the few remnants of the rule of law helped to counter the widespread efforts to hinder Arévalo from taking office. In a region where authoritarianism is and has been on the rise for the last two decades, this could either be a turning point or a short episode of resistance.

In 1992, the Salvadorean Peace Agreement served as a blueprint for the liberal peace agenda of the United Nations and Western countries. The underlying idea was that ending civil wars, democratising political regimes, and introducing market reforms would promote stable, democratic, and prosperous domestic environments. However, despite armed warfare ending in El Salvador, Guatemala and, Nicaragua, violence and corruption remained a significant problem in all three countries. Guatemala is a prominent example: The peace agreement (1996) envisioned fundamental changes such as the recognition of the rights of the indigenous population and a profound recasting of the state’s security sector with the establishment of a new civilian police and the reform of the judiciary. A failed referendum on the necessary constitutional changes in 1999 showed that these reforms were not only difficult but would likely not even happen.

Already in 2003, Susan Peacock and Adriana Beltrán published a study on Guatemala’s

hidden powers [that] protect themselves from prosecution through their political connections, through corruption, and when necessary through intimidation and violence. Their activities undermine the justice system and perpetuate a climate of citizen insecurity, which in turn creates fertile ground for the further spread of corruption, drug trafficking and organised crime. (Peacock and Beltrán 2003: 1).

Little has changed since. Others have framed these developments in transition economies as “state capture” (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann 2000). The 2007 assassination of Salvadorean members of the Central American parliament in Guatemala and the subsequent murder of the prime suspects in a Guatemalan high-security prison served as a wake-up call for the necessary establishment of an international commission to help fight corruption and impunity in Guatemala.

After a difficult start due to the lack of partners inside the judiciary, the CICIG (Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala, International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala) worked closely with independent Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz (a former human rights defender, 2010–2014) and Thelma Aldana (a former Supreme Court judge, 2014–2018). But when the CICIG, under the leadership of Colombian Iván Velasco, started to investigate and document party finances, entrenched networks of corrupt economic, political, and military elites fought back. Initially, the government of Jimmy Morales named María Consuelo Porras Argueta, a former deputy judge with close relations to those corrupt elites, as Attorney General and ended the CICIG’s mandate in 2019. Since then, corruption has mushroomed.

While the Donald Trump administration has not taken any action to counter this state of affairs, the Biden government started sanctioning corruption and anti-democratic behaviour in 2021 already. The so-called Engel List – continuously updated – includes persons

who have knowingly engaged in actions that undermine democratic processes or institutions, significant corruption, or obstruction of investigations into such acts of corruption (US State Department 2023)

in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. In 2021, Porras was added to the list (US State Department 2023).

Guatemalan politics is dominated by a fractured and personalised party system closely linked to economic and military elites. Congress has been a bottleneck for proposed reforms, with independent candidates and those advocating change having no chance in elections or of having legal reforms approved. However, significant civil society mobilisation in the streets helped to oust President Otto Pérez Molina, a retired general, and Vice President Roxana Baldetti in 2015. In 2022, both were sentenced to 16 years in jail due to their involvement in a high-profile customs- and tax-fraud scheme.

While the protest had been broad-based, no evident leadership emerged due to the ongoing selective political violence. The Movimento Semilla (Seed Movement), however, did take shape out of these protests, being registered by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (SET) in July 2017 before official recognition as a political party (Semilla) in November of the following year. Former Attorney General Aldana was its first presidential candidate in the 2019 elections; on the very same day of her inscription, however, a warrant was issued for her arrest. After receiving death threats, she left the country – as did many other human rights activists and independent judges in the face of continued harassment and criminalisation. Semilla would gain only six seats in parliament following its first electoral showing, but ultimately consolidated its profile as a force for change.

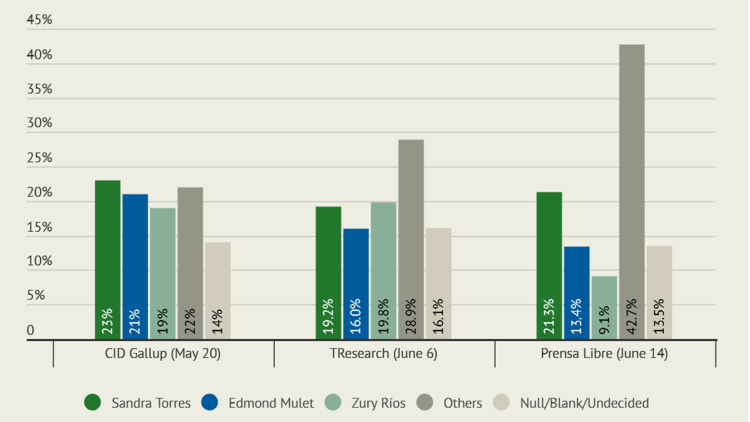

As discontent mounted in Guatemala before the 2023 elections, a series of relatively independent candidates emerged only to find themselves disqualified by the country’s corrupt political system: the centre-right Edmond Mulet; Thelma Cabrera, an indigenous left-wing leader; and Roberto Arzú, a right-wing candidate. Surprisingly, Semilla’s candidate, Arévalo, was not excluded – probably because he and Semilla were not perceived as a real threat having only scored in single digits in opinion polls (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Voter Preferences in the Run-Up to Guatemala Presidential Election (May–June 2023)

Source: Harrison 2023.

Note: Dates in parenthesis when poll was completed.

Against the odds, Semilla won 25 per cent of the congressional mandate. With 15.5 per cent of the vote, Arévalo made it into the run-off against Sandra Tores who received 21 per cent thereof. Here, he eventually won by a broad margin (61 to 39 per cent). As a consequence, the country’s corrupt elites began a series of actions to prevent Arévalo from taking office. They also weaponised the judiciary.

Weaponising the Judiciary

The autonomy of the judiciary is a core pillar of the rule of law and democracy: It interprets and applies a country’s laws in cases of dispute but also helps maintain equilibrium between the executive and legislative branches. At least in theory, it functions as a space for discussions of general interest and legal claim-making concerning the rights and responsibilities of state entities and individuals alike. This function, alongside the judiciary’s public authority, facilitatesthe defence of democratic norms via the law. An autonomous judiciary, hence, sets the rules for a democratic society and also reins in political excesses. In contrast, the loss of an independent judicial system may imply arbitrary use of the law, the dismantling of institutions from within, and autocratisation by abusing the Constitution and its provisions (Dixon and Landau 2021).

Against the broader backlash Guatemala had previously experienced, and as described above, such a weaponised judiciary enables elite networks and allied state agents in strategic positions to intervene in national elections. This state of affairs has led to extensive restrictions on presidential candidates’ electoral participation, Semilla’s legal status, as well as undermined the overall integrity of polls. Against these odds, the Guatemalan elections also exemplify the political use of law as a means of resistance.

Manoeuvres to derail democratic elections unfolded via/through the following state institutions: First, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (PPO), responsible for criminal persecution, in close collaboration with the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity and Consuelo Porras, who is at the same time the chief of the PPO and, as noted, Attorney General. Second, the Constitutional Court (CC), under the Supreme Court of Justice. Third, the SET, the highest entity in the electoral field. The latter is formally independent and does not make up part of the judicial system.

Even prior to the first voting round, the CC and the SET had excluded four presidential candidates. While not themselves affected by those decisions, Arévalo and Semilla came into the spotlight thereafter. The PPO quickly intervened, requesting that the criminal judge Fredy Orellana rescind Semilla’s legal status. This criminalisation was, however, not fully formalised either by the CC or the SET. A visit from Organization of American States delegates put pressure on the government and a writ of amparo wasled by Semilla to recover their status as a legitimate political party – but uncertainty remained. The amparo is a specific legal procedure of constitutional rank that permits reaction to the excesses of power. It emerged as a protective mechanism in Latin America and facilitates every citizen being able resort to this instrument when complaining about threatened and actual violations of his or her rights, also by state agents.

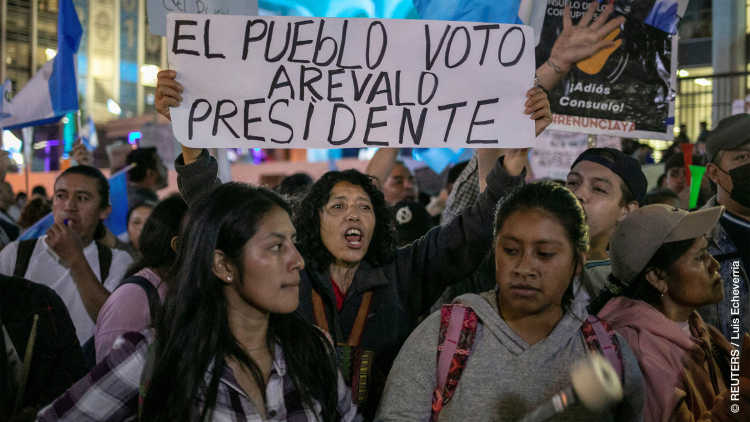

By then, the Guatemalan people had taken to the streets repeatedly, as led by indigenous movements uniting broad sectors of society. This mobilisation for democratic renewal, unprecedented since 2015, culminated in the run-off presidential election in August; Arévalo would win 61 per cent of the vote. While the elections became “an opportunity to resist backsliding“ (Schwartz and Isaacs 2023: 28), the PPO intervened in its aftermath. It claimed the election results were invalid, investigated the president-elect’s party, and raided SET headquarters to retrieve compromising material. Once more, massive protests erupted; the CC ordered the dispersal of any large-scale gatherings and the forceful breaking up of roadblocks. On 2 November 2023, the SET suspended Semilla’s legal status as a political party in line with the ongoing investigation. Again, this intervention was facilitated by an order issued by Judge Orellana on behalf of the PPO.

Finally, it was once more a writ of amparo – this timelodged by 10 claimants under coordinated civic action – that paved the way for a landmark decision. On 14 December 2023, the CC ruled to guarantee the January inauguration of president-elect Arévalo (Expediente 6175-2023). This definitive legal appeal against the interference of the PPO, the SET, and certain judges also included calls to Congress and all state entities to guarantee a peaceful handover of power. It also cited the submission of all state organs to the rule of law and the constitutionally established protection of transitions in office.

Arévalo was sworn in as president on 15 January 2024, together with Vice President Karin Herrera. The handover of power, originally scheduled for the day before, was eventually realised a few minutes after midnight due to disputes within Congress. Arévalo’s receipt of the presidential sash after a long delay symbolised a moment awaited with anxiety by Guatemalans and the international community alike, as well as a continued struggle for democracy in the country beyond just at the ballot box. The electoral process had turned into a prolonged back and forth, with the judicial system becoming an arena of heavy political contestation. On 11 January, former Minister of the Interior David Napoleón Barriento was arrested for having refused to forcefully stop protests back in October. On 19 January, the CC suspended Semilla from parliament’s Junta Directiva, implying that the party’s 23 parliamentarians would serve as independent representatives instead.

Elections: Not Always a Democratic Instrument

The large-scale mobilisation of civil society, predominantly driven by the country’s indigenous communities, was a clear signal of the desired change of government in Guatemala. This is a good omen for democracy. Despite the above-mentioned court order to disperse the widespread protests by force, Barriento, as noted, refused to fall in line. At least for the moment, the country’s traditional elites had failed despite playing most of the cards at their disposal to prevent the president-elect from taking office. This might be important beyond Guatemala, as democratic principles find themselves under challenge across Central and Latin America. Even free and fair elections can pave the way for aspiring autocrats. As described by Levitsky and Ziblatt (2018), once in office these governments devote themselves to dismantling democratic institutions and expanding their powers, claiming legitimacy for themselves and their policies by virtue of their electoral victory.

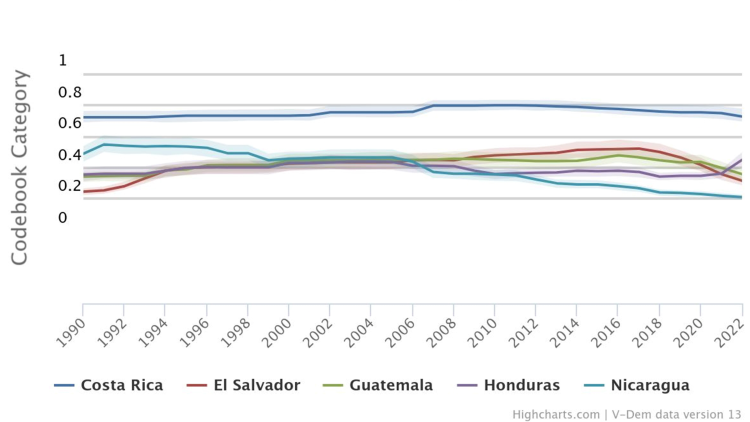

The most prominent case in Central America is El Salvador, where Nayib Bukele, president since 2019, has established a majority in parliament, eliminated judicial oversight and executive constraints, and established a permanent state of emergency – thus suspending civil rights and liberties. Although human rights violations have been widely documented (Cristosal 2023), there has been little civic mobilisation against the government. In part, this can be explained by the satisfaction of some segments of the population with a perceived increase in security. However, fear of reprisal is another key factor. The poor and marginalised in particular suffer under the state of emergency. These people often lack the resources and knowledge of legal recourse and/or have lost faith in state institutions. Despite, his undemocratic style of governance and open disregard for democratic rules of the game, Bukele’s popularity ratings are over 60 per cent according to opinion polls. While the judiciary at the beginning of Bukele’s presidency still challenged the executive, it has now been captured – and even assists the incumbent’s aspirations (e.g. by interpreting the Constitution in ways favourable to those wishes). On 4 February 2024, Bukele won another broad majority despite the Constitution precluding consecutive presidential terms.

Honduras follows a similar pathway, taking the Salvadoran style as an example (Silva Avalos 2023). This could be linked to the popularity of these measures, which may appear to offer future electoral success. An even more crude case is Nicaragua, where Daniel Ortega has established a full-fledged police state – therewith cementing a dictatorship in which he was allegedly just re-elected for another five-year term in the 2021 “elections.” Ortega claims that he and his party – the FSLN, which has controlled all of the country’s municipalities since the 2022 municipal elections – are the legitimate rulers with broad popular support. This logic generously ignores the fact that, first, elections cannot be considered free or fair and, second, many of those opposing his rule have since left the country.

The challenges to democracy thus continue, even in countries with relatively strong democratic foundations such as Costa Rica. Along with Uruguay and Chile, the latter has been considered a stable democracy for many years now. Although Costa Rica is still deemed a “liberal democracy” by V-Dem (2023a), civil rights and liberties have recently come under attack. Even in this former safe haven for journalists – especially from Nicaragua, and, more recently, El Salvador (e.g. from El Faro) –hostility towards independent reporters has continued to deepen (RSF 2023).

A PROLEDI (Programa de Libertad de Expresión y Derecho a la Información) (2023) report, itself based on a CIEP (Centro de Investigación y Estudios Políticos) survey, shows that while 63 per cent of Costa Rica’s populace is aware of attacks or offences against the press, 48 per cent say it is dangerous to work as a journalist; meanwhile, 54 per cent perceive censorship or restrictions to be imposed in general. It should be noted, however, that the judiciary (Constitutional Chamber) has so far stood up to President Rodrigo Chaves Robles’s attacks on the press. Latinobarómetro (2023) recently included Costa Rica in its list of “troubled democracies,” as based on a “very significant and simultaneous deterioration” in public support for democracy that leaves the country’s political system exposed and vulnerable to capture by elites. Overall, then, the foundations of democracy – such as electoral participation, civil society, and the rule of law – find themselves endangered both in Costa Rica and Central America at large.

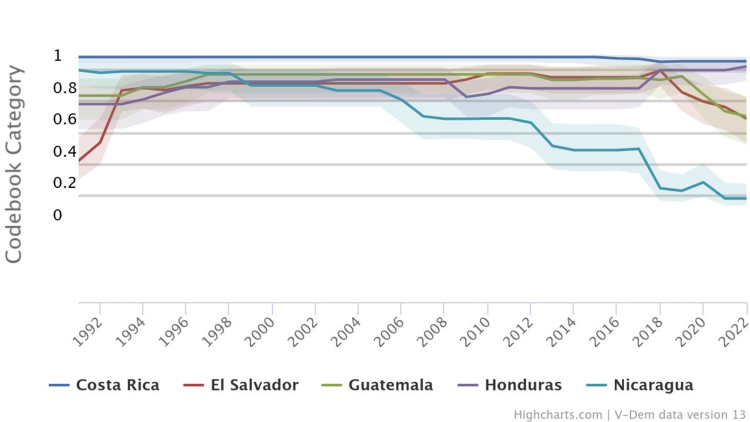

Figure 2. Central America Participatory Democracy Index

Source: V-Dem Institute 2023b.

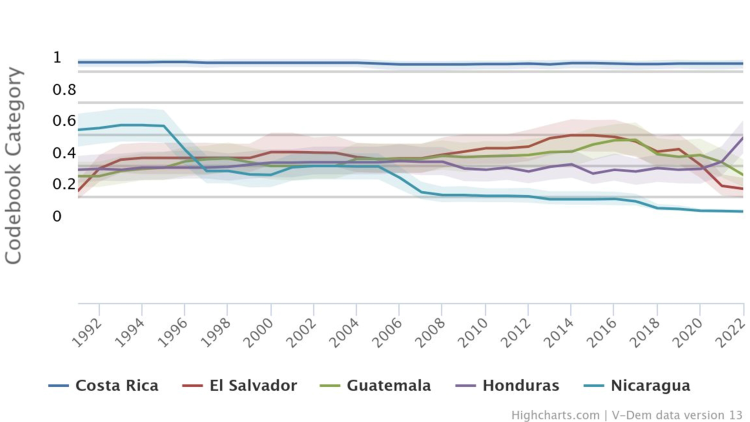

Figure 3. Central America Core Civil Society Index

Source: V-Dem Institute 2023b.

Figure 4. Central America Rule of Law Index

Source: V-Dem Institute 2023b.

The year 2024 is an election one in Latin America. The Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Uruguay, and Venezuela will all see their populaces go to the polls. The dissatisfaction with democracy due to corruption and an upsurge in or the fear of violence is likely to influence these elections. In these contexts, Bukele-style populists can appear an attractive alternative as anti-establishment figures who promise to cleanse state institutions of a corrupt elite. While incumbents failed to reverse electoral results in Guatemala (2024), Brazil (January 2023), and the United States (2021), the danger of autocratisation from within remains a distinct possibility. Not only democratic actors learn as they go; so do autocrats as well. Here, Nicaragua is a case in point. After his re-election in 2006, Ortega made sure that he would not lose again as he had done in 1990. Step by step, he subordinated the country’s democratic institutions to his family dictatorship. Arévalo’s triumph in Guatemala may therefore serve as a source of motivation for civil society throughout Central and Latin America when it comes to mobilising in defence of and struggling for democratic institutions and fundamental human rights. Identifying the conditions that make pro-democracy mobilisation more likely to succeed is hence imperative. One has to bear in mind here, however, that contexts vary across the region and that open anti-elite protests are more dangerous in some countries than in others.

Now at a crossroads, the example of Guatemala is illustrative of how pro-democracy mobilisation and participation can reclaim democratic elections – thus helping counter autocratisation. In various historical instances, civil society has shown a strong capacity to mobilise for democratic governance. This is true for the resistance against the self-coup by then-President Jorge Serrano in 1993, which led to the interim presidency of Human Rights Ombudsman Ramiro de León. In 2015, protests were key to ousting, as mentioned earlier, Pérez Molina and his vice president. Since 2023, mass demonstrations have been a key factor in the Arévalo government being allowed to take office.

With an eye towards the weeks ahead, challenges to the ability to govern and oversee reform will come first and foremost from traditional both legal and illegal elites and power groups – in certain cases, likely instigating violence. Furthermore, Semilla does not have a majority in Congress and needs support from other factions to pass and implement proposed reforms. A further issue relates to Guatemalan civil society’s lack of formal organisation. Protests and resistance need to be transformed and channelled into political advocacy and representation. Otherwise, the election of a reformist government could be a short-lived affair.

Beyond Democratic Elections

Central American societies form part of a global and geopolitical contestation of power and influence. As political scientist Larry Diamond remarked, “democracies do not rise or fall in a global vacuum” (Diamond 2022: 167). During the 1990s, the European Union, the UN, and the US invested significant money and resources into cooperative efforts to promote peacebuilding and democratisation in Central America. However, this engagement faded away with the growing importance of other trouble spots (e.g. the Balkans) or shifting political priorities (such as migration in the US).

In the current situation, which could mark a crucial turning point for Central America, regional and international actors must support democratic partners from state and society. Recent developments in Guatemala provide some important lessons here:

Strong legal mechanisms are important for resistance, such as the writ of amparo. Such legal instruments, according to specific contexts, should be considered complementary to protests and social movements’ collective action. In Guatemala, an amparo safeguarded Semilla’s legal status as a political party in July 2023; in October of the same year, it further led to a landmark decision by the CC. In both incidences, civil society used this instrument to counter specific mechanisms of autocratic encroachment directly, reclaiming and re-establishing the democratic application of the law.

Successful instances of resistance by means of lawfare, such as those recently witnessed in the Guatemalan case, can give a renewed, democratic significance to the judiciary – thus contributing to its (ongoing) legitimacy. International actors should continue to work on such mechanisms originating within the local context. Academia also has a role to play here. In consideration of the amparo of October 2023 demanding the handover of power after Guatemala’s recent polls, the Stanford Law School wrote an amicus curiae – a legal statement penned as a third party outlining the international standards applicable to the country’s elections, and thereby backing the legal arguments put forwards by local claimants.

Additional focus should be on the endeavours of indigenous people, who have been at the heart of pro-democracy protest movements; political actors have, in recent decades, largely ignored them, however. These individuals make up around half of Guatemala’s overall population. Their fight against the extractivist development model and for their social, economic, and cultural collective rights are essential for sustainable development and policies to mitigate climate change’s effects. Indigenous communities in the country’s highlands are among the poorest and most affected by the climate crisis, but they also have highly creative traditions of environmental protection and political organisation.

Last but not least, pro-democracy regional and international actors need to learn that a democratic electoral system does not per se guarantee political and civil rights – even less so collective ones. Across the world, we see the rise of authoritarian actors elected to office who then use their power to undermine the core institutions integral to a democracy’s functioning. The restriction of judicial independence stands at the heart of these hostile policies, as the cases of El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Venezuela all highlight. Further factors that should serve as early-warning mechanisms are the intimidation, imprisonment, and assassination of human rights activists, social leaders, trade unionists, and independent/non-corrupt judges, police, and journalists. These are key reform actors without whom democracy can neither flourish nor recover. These omens should be taken seriously: it might already be too late once these individuals and institutions are no longer here. While sanctioning corrupt and undemocratic behaviour certainly aids pro-democracy actors, more collaborative and bottom-up formats are required to safeguard democracy itself – not only in the Latin American region but around the world, too.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Cristosal (2023), One Year Under State of Exception: A Permanent Measure of Repression and Human Rights Violations, accessed 29 January 2024.

Diamond, Larry (2022), Democracy’s Arc: From Resurgent to Imperiled, in: Journal of Democracy, 33, 1, 163–179.

Dixon, Rosalind, and David Landau (2021), Abusive Constitutional Borrowing: Legal Globalisation and the Subversion of Liberal Democracy, Oxford University Press.

Harrison, Chase (2023), Poll Tracker: Guatemala’s 2023 Presidential Election, AS/COA, 23 June, accessed 7 February 2024.

Hellman, Joel S., Geraint Jones, and Daniel Kaufmann (2000), “Seize the State, Seize the Day” State Capture, Corruption, and Influence in Transition, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper Series, 2444, accessed 7 February 2024.

Latinobarómetro Database (2023), Latinobarómetro Informe 2023. La Recesión Democrática de América Latina, Santiago de Chile: Latinomarómetro.

Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt (2018), How Democracies Die, New York: Crown Publishing.

Peacock, Susan C., and Adriana Beltrán (2003), Hidden Powers in Post-Conflict Guatemala: Illegal Armed Groups and the Forces behind Them, Washington, DC: Washington Office on Latin America.

PROLEDI (2023), Encuesta sobre libertad de expresión y confianza en medios de comunicación RESUMEN EJECUTIVO DE RESULTADOS, Universidad de Costa Rica, PROLEDI, accessed 7 February 2024.

RSF (Reporters Without Borders) (2023), 2023 World Press Freedom Index – Journalism Threatened by Fake Content Industry, accessed 29 January 2024.

Schwartz, Rachel A., and Anita Isaacs (2023), How Guatemala Defied the Odds, in: Journal of Democracy, 34, 4, 21–35, accessed 29 January 2024.

Silva Avalos, Héctor (2023), States of Exception: The New Security Model in Central America?, WOLA, 22 February, accessed 29 January 2024.

US State Department (2023), Report to Congress on Foreign Persons who have Knowingly Engaged in Actions that Undermine Democratic Processes or Institutions, Significant Corruption, or Obstruction of Investigations Into Such Acts of Corruption in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua 22 USC 2277a(b): Targeted sanctions to fight corruption in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, accessed 7 February 2024.

V-Dem Institute (2023a), Defiance in the Face of Autocratization, Democracy Report 2023, University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

V-Dem Institute (2023b), “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v12” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, accessed 1 February 2024.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Forschungsprojekt

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Kurtenbach, Sabine, Désirée Reder, und Alina Ripplinger (2024), Guatemala: A Vote for Turning the Tide, GIGA Focus Lateinamerika, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-24012

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.