- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The “New Turkey” Might Have Come to An End: Here’s Why

GIGA Focus Middle East

The “New Turkey” Might Have Come to An End: Here’s Why

Number 2 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Combining formal democracy, neoliberal capitalism, and conservative Islam, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) transformed state–society relations in Turkey dramatically after its first electoral victory in 2002. Yet the elections to be held on 14 May 2023 might mark the end of an era defined as the “New Turkey” by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself. There are three key catalysts here.

Until recently, AKP pursued an economic growth model that brought together a ruling bloc consisting of various social forces and state actors. Simultaneously, it reproduced mass consent leading to consecutive electoral victories. Yet, the current economic crisis makes the maintenance of the incumbent party’s electoral support extremely difficult.

On 6 February, southern Turkey was struck by the deadliest earthquakes in the country’s history. The government’s highly politicised yet wholly inadequate management of the crisis exacerbated the earthquakes’ adverse effects, harming Erdoğan’s image and posing another challenge for the ruling coalition in the upcoming elections.

Despite Erdoğan’s frequent attempts to sow discord among his critics, the opposition seems to have learnt its lesson from past mistakes, uniting behind the main oppositional candidate, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who will significantly challenge the ruling coalition.

Policy Implications

The response of European politicians to Turkey’s increasing authoritarianism in the recent past has not gone beyond expressing “deep concerns,” focusing on short-term interests such as the containment of refugee flows and pursuing a transactional relationship with the incumbent president. The upcoming elections are a watershed moment for Turkey’s threatened democratic institutions. European governments need to reconsider their approach, since a rules-based mode of engagement would benefit both the European Union and Turkish society in the long run.

Towards a Deadlock in Manufacturing Consent

Political scientists studying Turkish politics recently engaged in fervent discussion about how to classify the current Justice and Development Party (AKP) regime. “Competitive authoritarianism,” “authoritarian neoliberalism,” “neoliberal populism,” and “crony capitalism” are just a few of the conceptualisations put forward so far. Yet, one thing that these accounts agree on is that Turkey gradually took an authoritarian turn when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became a prototypical example of the populist leader in the new millennium. Concomitantly, there is also a broad consensus that Turkey is going through an economic crisis, with high levels of current account deficit and foreign debt, massive inflation rates, the devaluation of the Turkish lira, as well as rising unemployment and household debt since 2018. These increasing economic problems are making it difficult for the AKP government to attract support, crucial for the upcoming presidential and general elections on 14 May.

Having overcome a closure trial in 2008, mass uprisings in 2013, and a failed coup attempt in 2016, the AKP is a unique case in the political history of Turkey – which witnessed several unstable and short-lived coalition governments particularly during the 1990s. How, then, did the AKP manage to maintain its electoral success and dominate Turkish politics for more than 20 years despite such challenges? Much of the literature examines the AKP regime with reference to its Islamism and identity politics. Yet, a political economy perspective might provide a more satisfactory outlook here since the AKP is above all a neoliberal party alongside its conservative and Islamist identity. Indeed, the AKP managed to form and maintain a hegemonic ruling bloc consisting of various social forces and state actors throughout its rule while simultaneously also reproducing mass consent via a “welfare effect created through borrowing” (Bekmen and Özden 2022: 9). After coming to power in 2002, the AKP devoted itself to the ongoing implementation of neoliberalism and achieved remarkable economic growth rates based on foreign-capital inflows and credit expansion. Combining its “moderate conservatism” with a Western-oriented position and neoliberal policies, the AKP not only secured European Union and United States support but also became the “darling” of international financial institutions throughout the first decade of the new century. Relying on both domestic and foreign support, the AKP also restructured civil–military relations and curbed the long-standing military tutelage that had dominated Turkish politics until then.

Having consolidated its political hegemony and largely pacified major state institutions such as the military, parliament, and the judiciary, the AKP put a de facto end to the separation of powers in the second decade of its rule. It increasingly strengthened the executive’s control over the judiciary, and concentrated unprecedented power in the hands of Erdoğan, suppressing all forms of opposition that challenged his leadership and policies throughout the 2010s. Ending peace talks with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) (also called “Kurdish Opening”) in 2015, the AKP increasingly adopted a nationalist discourse and reconfigured its ruling bloc in allying with nationalists after the mid-2010s. The transformation of the state structure was gradually carried through by the 2007, 2010, and 2017 constitutional referenda that introduced changes to the executive and the judicial system, the declaration of a state of emergency following the 2016 coup attempt, and by the entry into force of presidentialism in 2018. The strengthening of the executive was also reflected in Erdoğan’s own statements, who publicly defied key institutions such as the Constitutional Court as well as any form of societal opposition such as the Gezi Park protests in 2013. During the restructuring of the state, the AKP hardly encountered any international opposition. The EU responded with “malign neglect” to Turkey’s authoritarian turn due to the refugee deal while US President Donald Trump expressed his admiration for authoritarian leaders globally, including Erdoğan (Uzgel 2020: 74–76). Today, Turkey’s incumbent regime extensively rests on the personification of political rule, criminalisation of the opposition, restrictions on the freedoms of expression and assembly, and on the erosion of the rule of law and judicial independence.

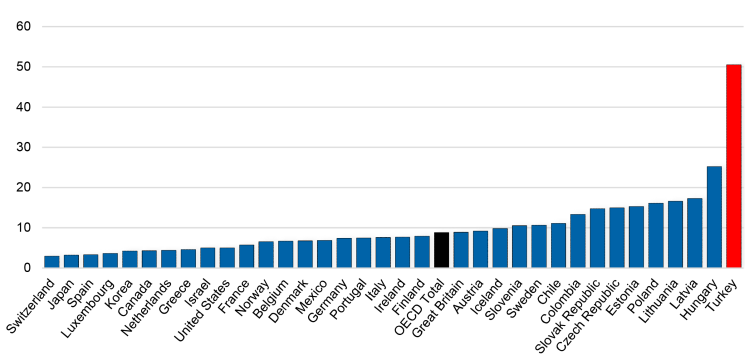

Despite Erdoğan’s consolidation of executive power, however, it has become more and more difficult for the AKP to sustain its foreign capital-dependent, domestic demand-driven, and debt-led growth model. By the second half of the 2010s, Turkey’s economy started to encounter numerous problems such as instability in foreign-exchange markets, debt-repayment problems, soaring inflation (peaking at 85.51 per cent annually in October 2022), and rising unemployment (Orhangazi and Yeldan 2021: 461). Figure 1 below depicts the OECD countries’ annual growth rates for inflation, which Turkey leads with one of 50.5 per cent as of March 2023.

Figure 1. Total Annual Inflation Growth Rate as of March 2023 (Consumer Price Index, in %)

Source: OECD (2023a).

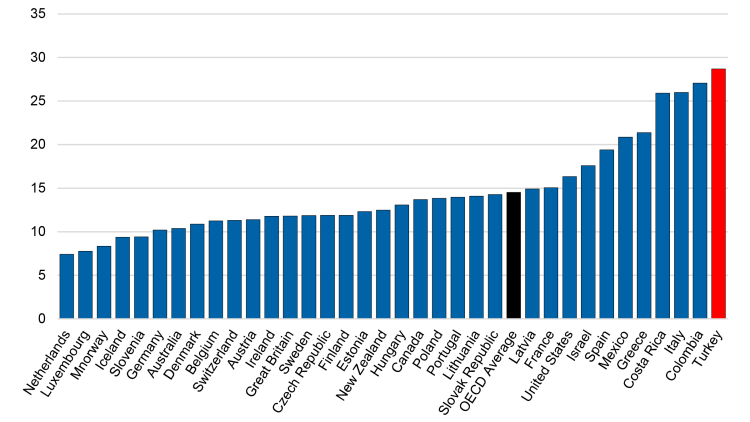

Turkey’s unemployment rates also showed an upward trend throughout the 2010s and peaked at 13.7 per cent in 2021, the highest figure that the country has seen during the AKP era. The latest available data shows that the percentage of Turkish youth not in employment, education, or training is the highest among OECD countries at 28.7 per cent – the OECD average is 14.5 per cent (see Figure 2 below). Soaring inflation and rising unemployment are not the only problems, though. By August 2018, economic growth slowed down and the country also experienced a currency crisis, with the Turkish lira losing 35 per cent of its value against the US dollar. Since then, the Turkish lira has become extremely volatile, with the Erdoğan government struggling to maintain the currency’s value – which had even appreciated against the US dollar during the boom years of the first decade of the new millennium.

Figure 2. Youth Not in Employment, Education, or Training as of 2021 (15–29 Year Olds, in %)

Source: OECD (2023b).

Beyond doubt, changing global economic conditions also exacerbated the problems arising in Turkey and led the country into a related crisis in the second half of the 2010s. The US Federal Reserve’s declaration in May 2013 that it would move away from expansionary monetary policies and its managed increase of interest rates from 2015 to 2019 led to a global tendency for capital flight from peripheral economies to core countries (Bedirhanoglu 2021: 77). Combined with the numerous political crises with the US (such as the arrest of priest Andrew Craig Brunson in 2016 and the purchase of S-400 missiles from Russia in 2017), this also slowed down much-needed capital inflows into the Turkish economy. To shore up the failing economy and ultimately pull in votes during the upcoming elections, Erdoğan has even changed course in foreign policy and attempted to boost investment from Persian Gulf monarchies in recent years. However, these inflows have remained limited and the eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic would only worsen the country’s economic conditions – intensifying foreign-capital outflows, leading to a depletion of Central Bank reserves and the Turkish lira hitting new lows, and therefore increasing the risk of a balance-of-payment crisis (Orhangazi and Yeldan 2021: 461). The recent earthquakes are expected to cost another USD 104 billion to the Turkish economy as declared by Erdoğan himself, deepening the already-heavy burden of the country’s wider economic crisis. When asked about what the most important problem facing Turkey is, respondents in an established survey most frequently said the economy (33.9 per cent) while unemployment came second (19.5 per cent) – that already in October 2020 (Türkiye Raporu 2020). Together with additional economic problems such as the rising cost of living, the AKP faces a serious challenge to maintain its support in the upcoming elections on 14 May.

The Post-Earthquake Response and Its Potential Implications

On 6 February, southern Turkey and northern Syria were struck by two earthquakes (with magnitudes of 7.7 and 7.6 on the Richter scale respectively), going down as the deadliest in Turkey’s history. Affecting 11 cities and more than 13.5 million people in total, the earthquakes led to more than 50,000 deaths in Turkey alone. Multiplying their adverse effects was the government’s poor emergency response (Tol 2023). It dramatically altered the country’s public agenda and led to mounting criticism of the AKP government. The aftermath of the earthquakes proved that the ruling government had failed to prepare the country for such a scenario despite repeated warnings from seismologists (as well as a number of other earthquakes occurring in the recent past).

One of the most voiced criticisms of the government was regarding its highly politicised yet wholly inadequate response. In the immediate aftermath, for instance, Erdoğan preferred to call the municipality heads of all affected cities except for the main opposition’s mayors of Hatay and Adana, whom he spoke to hours later only on mounting criticism. The initial days of the disaster witnessed victims crying out for help on social media, with news agencies reporting that the screams of those lying under the rubble were relentless. The early days were crucial for rescuing survivors and the injured, particularly since the earthquakes had struck under harsh winter conditions – with temperatures falling into the minuses during the night. Although Erdoğan refused to accept criticism of the country’s limited and belated emergency response initially, he would later acknowledge shortcomings to the state’s response and ask for forgiveness from Turkish citizens (BBC 2023).

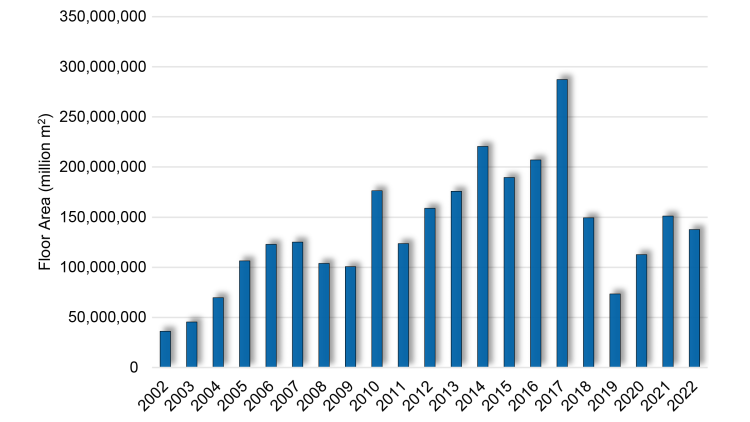

The Turkish government’s limited and delayed emergency response was only a part of the problem, however. In fact, the main disaster-management authority’s (AFAD) incapability to coordinate aid, as well as pre-earthquake housing and construction policies, exacerbated the severity of these events. On the second day after the earthquakes had struck, celebrities and football players shared videos of aid-loaded trucks queueing at the entrance to affected cities, waiting for AFAD’s approval to deliver their goods. The Turkish Red Crescent (Kizilay) was similarly criticised; as it turned out, the organisation sold tents to non-governmental organisations instead of distributing them for free based on need. Despite mounting public calls for resignations, not a single person left their post from either institution. The government’s pre-earthquake housing and construction policies were similarly criticised by the public and on mainstream television channels in the immediate aftermath. In Turkey, zoning amnesties have been a policy frequently resorted to as a way to obtain electoral support (also before the AKP era). Consecutive AKP governments continued this trend, releasing nine zoning amnesties in total and providing documents for potentially insecure and vulnerable construction. After the release of the last zoning amnesty in 2018, the Ministry of the Environment and Urbanisation declared that 8.9 million citizens had applied for a construction permit. Figure 3 below shows the increase in issued construction permits during the AKP era, generally seeing an upward tendency except for a relative decrease after 2017. This has led to a questioning of the government’s construction policies, as largely fuelling economic growth in Turkey during the AKP era. Erdoğan recently expressed his regret also over the issuing of zoning amnesties throughout his rule.

Figure 3. Construction Permits regarding Floor Area of Buildings, 2002–2022

Source: TUIK (2023).

While the emergency response was slow and limited, the government’s reaction to soaring criticism was rapid and extensive. Calling critics “undignified people” on the second day, Erdoğan announced that the government was “taking notes” of those allegedly distributing “fake news” and argued that such catastrophes were a part of “destiny.” The following days witnessed mainstream TV channels going suddenly off air when victims criticised the government’s failure to provide sufficient emergency relief to the affected region. Several journalists faced bans, detentions, and judicial investigations for “disseminating fake news.” Unable to silence criticism, the government chose to restrict access to social media for hours, where, as noted, victims had been requesting help from under the rubble. All these developments caused anxiety and trouble on the government’s side and strengthened the view that, perhaps for the first time, the chances of the opposition beating Erdoğan in the upcoming elections have never been so high.

Coalitional Alliances and the Election Setup

On 14 May, Turkish citizens will vote to choose their new president during the “world’s most important election [of 2023]” (Ghosh 2023). Both the government and the main opposition parties are entering the elections with coalitional alliances. The election result is expected to be determined by three main alliances, the constituents of which are shown in Figure 4 below. Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance (Cumhur) encompasses five political parties other than the AKP: the Nationalist Action Party (MHP), Great Unity Party (BBP), New Welfare Party (YRP), Free Cause Party (HÜDA PAR), and the Democratic Left Party (DSP). Whereas MHP and BBP are known for their ultra-nationalist leanings and have already been within Erdoğan’s ruling coalition, YRP, HÜDA PAR, and DSP are small newcomers to the coalition. YRP and HÜDA PAR have extremist discourses and positions on issues such as woman’s rights and the reintroduction of the death sentence. The latter is also widely accepted as the political representative of the Hezbollah movement in Turkey, previously involved in acts of violence throughout the 1990s. The main oppositional Nation’s Alliance (Millet) is led by the head of the centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, and encompasses five other political parties that are on the centre-right of the political spectrum: the Good Party (IYIP), Felicity Party (SP), Future Party (GP), Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA), and the Democrat Party (DP). Among these, IYIP is a secularist nationalist offshoot of MHP, GP and DEVA are two offshoot parties of the AKP (led by two former ministers), SP is the predecessor of the AKP, and DP is a relatively small party. A third coalition is the left-wing Labour and Freedom Alliance (Emek ve Özgürlük) formed by the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), Workers’ Party of Turkey (TIP), Labour Party (EMEP), and several other grassroots parties and organisations with socialist leanings. Whereas HDP represents Kurds and voices their democratic demands (among other claims), TIP has gained in popularity in recent years and is expected to be represented in parliament also in the upcoming legislative period.

Figure 4. Constituents of the Main Coalitional Alliances and Their Presidential Candidates

Source: Author’s own illustration; © Wikimedia Commons (left photo); © Wikimedia Commons (right photo).

Ruling the country since the 2002 general elections, the AKP had promised during the 2017 referendum improvements in a variety of areas under presidentialism – including a more efficient system of governance, smoothly functioning institutions, and a faster-growing economy. Although the referendum passed by a slight margin and the presidential system became effective in 2018, it is hardly possible to say that the country has made genuine progress in any of these areas. Under Turkey’s new political system ruled by a strengthened executive, the state bureaucracy has become extremely dependent on the approval of the president and its institutions are incapable of functioning autonomously. “By the order of our president” has become a frequently repeated introductory sentence of ministers and bureaucrats to prove loyalty, and state institutions have turned into administrative offices that simply follow the instructions of the one-man ruler regardless of the policy area in question. Bureaucrats who dare to disobey or diverge from the orders of Erdoğan are likely to be sacked, as has been the case with several Central Bank governors recently. A recent Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) study posited that presidentialism has weakened parliament, undermined local government, made the judiciary dysfunctional, and led to emigration and capital flight, among other things (Adar and Seufert 2021).

Combined with the economic crisis and the poor disaster management in the aftermath of the earthquakes, the AKP’s unfulfilled promises have caused difficulties for Cumhur to develop an effective electoral strategy – leading many to argue that the opposition has a significant chance of beating Erdoğan this time. Yet this is no easy task for Millet, since the government still possesses levers of power such as subsidies and handouts that could potentially strengthen its weakened position prior to election day (Aydintasbas 2023). Accordingly, the government increased the minimum wage twice in 2022 to keep up with soaring inflation; Erdoğan also recently announced that the government plans an additional mid-year increase in the minimum wage, too. Pledging that energy and electricity prices will also be reduced by 20 and 15 per cent respectively, the government eliminated age requirements on retiring for around two million citizens – who will be able to do so earlier now. Erdoğan recently also said that monthly minimum pension payments will be increased from TRY 5,500 to 7,500 (USD 390). Besides these economic instruments, the ruling coalition also has extensive leverage over media outlets – the vast majority of which are owned by pro-government businesspeople. A handful of remaining critical platforms are facing censorship and punitive measures such as media blackouts when nurturing distaste for the ruling coalition. The government’s grip over state institutions such as the security apparatus, judiciary, and the Supreme Election Board (YSK) makes the campaign trail anything but fair, raising concerns about electoral safety and posing yet another difficulty for the opposition. Whether such initiatives and advantages will suffice to restore the waning reputations of Erdoğan and Cumhur remains to be seen.

On the other hand, Millet nominated the head of CHP, Kılıçdaroğlu, as their presidential candidate despite initial reluctance from IYIP, which declared that it had left the alliance on 3 March. Arguing that the candidate had been imposed on the alliance without proper discussion, it then re-joined after only three days on mounting criticism from within the opposition. The quarrel seems to have consolidated Kılıçdaroğlu as Millet’s main presidential candidate, helping quell voices within the opposition critical of his candidacy. Kılıçdaroğlu, who gained sympathy and credit particularly with his stance in the aftermath of the earthquakes, is now Erdoğan’s main competitor in the upcoming elections. He successfully rejected the silencing of the opposition in the aftermath of the earthquakes and overcame government pressures demanding not to “politicise” the disaster. The Ankara and Istanbul mayors of his party have been actively involved in delivering aid to the affected region while he has continuously held the government and its policies responsible for a heavily mismanaged emergency response. Besides his post-earthquake performance, Kılıçdaroğlu has repeatedly cited Erdoğan’s corruption – announcing that during its 20 years in power, the government has transferred USD 418 billion to pro-government businesses, whom Kılıçdaroğlu continuously calls “gangs.” Kılıçdaroğlu has also been praised for his ability to keep together parties with different ideological and political leanings within the alliance, avoiding potential conflicts within Millet on issues such as the scope of cooperation with Kurds and the nomination of vice-presidential candidates. Recent opinion polls reflect Kılıçdaroğlu’s growing popularity in the last few months, showing him ahead of Erdoğan for the first time – albeit only by a slight margin in what is ultimately a neck-and-neck race.

On 30 March, Millet issued a “Memorandum of Understanding on Common Policies” that entails reforms and policy changes in case of electoral victory in the following areas: Law, Justice, and Judiciary; Public Administration; Anti-Corruption, Transparency, and Audit; Economy, Finance, and Employment; Science, Research and Development, Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Digital Transformation; Sectoral Policies; Education and Training; Social Policies; and Foreign Policy, Defence, Security, and Migration Policies (CHP 2023). Since its formation on 5 May 2018, Millet’s most prominent pledge has been the restructuring of the state bureaucracy based on merit and the return to a “reinforced” parliamentarian system, cleansed of personalised and arbitrary governance. Millet representatives announced that they are seeking to form an effective and participatory legislative body and introduce a system of governance based on the separation of powers and effective checks and balances. The Memorandum embraces other promises such as the lowering of the electoral threshold to 3 per cent (currently 7 per cent), the immediate implementation of Constitutional Court and European Court of Human Rights rulings, the renewed neutrality of key institutions such as the judiciary and state-owned media, as well as the removal of obstacles to the freedoms of expression and assembly. To what extent Millet would be able to realise such promises in case of electoral victory, however, depends on a number of factors including intra-alliance negotiations and inter-party bargaining.

The Third and Likely Pivotal Coalition

Yet another coalition that is likely to have a major impact on the upcoming elections is the Labour and Freedom Alliance, formed officially on 25 August 2022. The background to this is as follows: After the AKP government put an end to the ongoing “Kurdish Opening” and took a nationalist turn in 2015, the earlier-mentioned HDP became one of the main targets of the incumbent regime’s criminalisation and stigmatisation. A highly politicised judiciary not only imprisoned the party’s former co-chairs Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ in 2016 but also removed almost all democratically elected HDP mayors after the 2019 municipal elections. Currently, there is an ongoing judicial case that could still outlaw HDP and prevent it from running in the upcoming elections. Yet HDP seems to have outmanoeuvred this by entering the elections under the banner of the Green Left Party (YSP), one of the constituents of the Labour and Freedom Alliance.

Besides the criminalisation of HDP, Millet’s constituent parties have also faced restrictions and judicial cases. The rulings against CHP’s Istanbul mayor (for calling the YSK’s members “fools”), and its provincial head of Istanbul (for insulting the president) are among recent attempts to undermine oppositional figures and CHP. In 2019, Erdoğan did not refrain from annulling municipal elections in Istanbul via a highly politicised YSK decision based on dubious accusations of fraud. This backfired, however, and the current CHP mayor won the re-held elections by an even higher margin. The criminalisation and targeting of the opposition was approved by Erdoğan himself, who, for instance, praised an attempted attack on IYIP’s leader, saying that the suspects “taught her a lesson” and threatening that “more will follow” (Duvar English 2021).

Throughout his 20 years of rule, Erdoğan has been mostly able to gain the upper hand in consecutive elections by dividing the opposition. In the recent past, HDP was criminalised to segregate out Millet’s nationalist constituents (mainly IYIP) from the alliance and prevent Kurds from supporting Kılıçdaroğlu in the upcoming elections. Nevertheless, opposition parties have been able to maintain their united stance so far – thus posing a major challenge to Erdoğan’s Cumhur and gaining a considerable advantage over it. The HDP-led alliance recently declared that they will not nominate their own presidential candidate and so are likely to support Kılıçdaroğlu. In return, the latter visited the current co-chairs of HDP, further to criticising the ongoing judicial cases against the party and emphasising the need to find a political solution to the Kurdish conflict. Having received close to six million votes (11.7 per cent) in the 2018 elections, HDP is considered a potentially key determinant of who the new president will be, ringing further alarm bells for Erdoğan and Cumhur.

The presidential and general elections on 14 May represent a critical juncture in Turkey’s political history. If Erdoğan’s ruling coalition wins despite its currently disadvantaged position, his repressive one-man rule will be consolidated, state institutions will be undermined to an even larger degree than they already are at present, fundamental rights and freedoms will be wiped out, and the country’s already-weakened democracy will be obliterated. European politics has so far adopted a transactional mode of engagement with Erdoğan and pursued short-term interests such as the containment of the refugee influx into Europe. This has both cost countless human lives in the Mediterranean Sea and led to the failure to develop a rules-based approach to Turkey’s democratic backsliding. Turkish citizens’ demand for democracy is greater than ever, and the united stance of the opposition presents a considerable electoral advantage for Kılıçdaroğlu. European politicians need to reconsider their transactional approach more than ever, and thus formulate a long-term perspective on EU–Turkey relations.

Footnotes

References

Adar, Sinem, and Günter Seufert (2021), Turkey’s Presidential System after Two and a Half Years: An Overview of Institutions and Politics, SWP Research Paper, 2021/RP 02, 1 April, accessed 24 April 2023.

Aydıntaşbaş, Aslı (2023), Turkey’s Opposition has a Chance to Beat Erdogan. It won’t be Easy, in: Washington Post, 3 December, accessed 24 April 2023.

BBC (2023), Turkey Earthquake: Erdogan Seeks Forgiveness Over Quake Rescue Delays, 27 February, accessed 24 April 2023.

Bedirhanoğlu, Pınar (2021), Global Class Constitution of the AKP’s “Authoritarian Turn” by Neoliberal Financialization, in: Errol Babacan, Melehat Kutun, Ezgi Pınar, and Zafer Yılmaz (eds), Regime Change in Turkey: Neoliberal Authoritarianism, Islamism and Hegemony, New York: Routledge, 68–84.

Bekmen, Ahmet, and Barış Alp Özden (2022), The Rise and Demise of Neoliberal Populism as a Hegemonic Project: Brazil, Thailand, and Turkey, in: Rethinking Marxism, 34, 3, 338–360.

CHP (2023), Memorandum of Understanding on Common Policies (January 30, 2023), accessed 24 April 2023.

Duvar English (2021), Erdoğan Praises Attack Attempt Against İYİ Party Leader, Implies that More Will Follow, 26 May, accessed 24 April 2023.

Ghosh, Bobby (2023), The World’s Most Important Election in 2023 Will Be in Turkey, in: The Washington Post, 1 September, accessed 24 April 2023.

OECD (2023a), Inflation (CPI), (Data set), accessed 24 April 2023.

OECD (2023b), Youth Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET), (Data set), accessed 24 April 2023.

Orhangazi, Özgür, and Alp Erinç Yeldan (2021), The Re‐Making of the Turkish Crisis, in: Development and Change, 52, 3, 460–503.

Tol, Gönül (2023), How Corruption and Misrule Made Turkey’s Earthquake Deadlier, in: Foreign Policy, 2 October, accessed 24 April 2023.

TUIK (2023), Floor Area (Squar Meter) According To Construction Permits, 2002-2022, accessed 24 April 2023.

Türkiye Raporu (2020), Türkiye’nin En Önemli Sorunu Nedir?, 26 October, accessed 24 April 2023.

Uzgel, İlhan (2020), Turkey’s Double Movement: Islamists, Neoliberalism and Foreign Policy, in: Pınar Bedirhanoğlu, Çağlar Dölek, Funda Hülagü, and Özlem Kaygusuz (eds), Turkey’s New State in the Making: Transformations in Legality, Economy and Coercion, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 64–79.

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Smith Reynolds, Aaron (2023), The “New Turkey” Might Have Come to An End: Here’s Why, GIGA Focus Middle East, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfme-23022

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.