- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Under Pressure: Democratisation Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa

GIGA Focus Africa

Under Pressure: Democratisation Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa

Number 4 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3603

Military coups, leaders abolishing constitutional term limits, and violent conflicts undermining democratic governance have made headlines in sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. However, longitudinal data from key democracy indices and survey data from Afrobarometer reveal that the state of democracy in Africa is better than expected in certain regards.

Democracy indices show a strong increase for sub-Saharan Africa since 1990. While only relatively few countries qualify as “democratic” and many more remain in the grey zone between democracy and autocracy, recent “backsliding” trends have not offset past gains.

Although frequently dissatisfied with their leaders and with how democracy works, two-thirds of Africans support democracy while even bigger majorities reject authoritarian alternatives.

Africans’ support for it already makes an independent case for democracy. In addition, democracy also means freedom from oppression as well as the right to choose one’s rulers. Democratic systems can manage conflicts peacefully and are arguably better for socio-economic development.

Major threats to democracy include adverse socio-economic conditions, intergroup conflicts, a politicised military, and authoritarian-minded civilian leaders. External factors such as support for dictators, the influx of authoritarian ideologies and narratives, as well as increased external rivalries over “zones of influence” pose a special threat.

Policy Implications

While only Africans will make democracy work, external influences can make a difference here. Western countries need to avoid supporting authoritarian leaders and stop prioritising geopolitical interests over genuine support for democracy. Democratic governments and pro-democratic societal actors should be treated preferentially. It is also important to stress that “democracy” is not a concept imposed by the West but means freedom from oppression for all people.

The “African Spring” Has Already Happened

Outside views on Africa regularly focus on negative aspects, often stereotypes. Besides disease, poverty, and violent conflict, military coups and authoritarian leaders frequently make headlines too. It is not uncommon for questions to arise about when an “African Spring” – like the Arab Spring – will eventually happen. The happy but possibly surprising truth is that the African Spring has already occurred. A wave of democratisation hit the continent after the end of the Cold War. One-party governments as well as personal and military dictatorships came under acute pressure. By the early years of the new century, almost all African countries had introduced multiparty electoral systems.

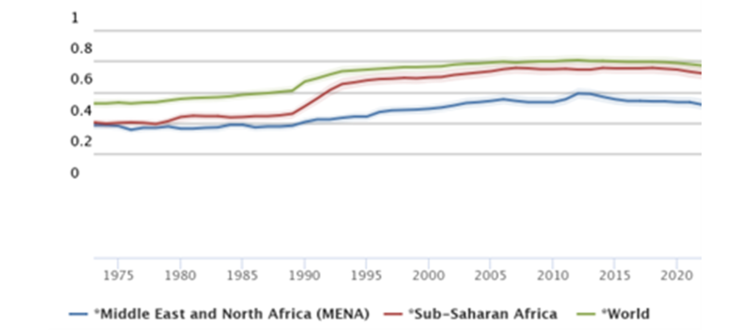

Figure 1 below depicts the trends vis-à-vis democracy’s spread and resilience over time, based on data from the Varieties of Democracy Project (2023). Here, democracy is operationalised as “polyarchy” – a term coined by Robert A. Dahl (1998), meaning “rule of the many.” Polyarchy is different from “ideal democracy” in that is very difficult or even impossible to achieve and exists nowhere – also not in Western countries. Ideal democracy would require perfect political equality of all citizens, for instance. In terms of content, polyarchy means a both competitive and participatory form of government. More specifically, polyarchy requires free and fair elections that generally allow active and passive political participation and most importantly actually serve to determine rulers. Polyarchy is accompanied by the freedoms of expression and association as well as alternative sources of information. By and large, polyarchy is functionally equivalent to what other political scientists call “liberal democracy.”

When we look at the long-term trends in Figure 1, we can see the steep increase in democracy for sub-Saharan Africa in the decade from 1990 to 2000. Starting around 2015, meanwhile, we observe what is called “democratic backsliding” (e.g. Arriola, Rakner, and van de Walle 2022). A downward trend cannot be denied and finds its most visible expression in the sudden breakdown of democratic rule in countries like Burkina Faso, Guinea, or Mali – and most recently Niger, the “last democracy standing” in the Sahel. Burkina Faso had democratised only shortly before it fell prey to instability and then military coups. Benin, like Mali hitherto often hailed as a showcase of democracy in Africa, showed a less dramatic breakdown, but has seen the increasing domination of the executive – as affecting the competitive nature of elections.

The Glass Is (Only) Half-Full

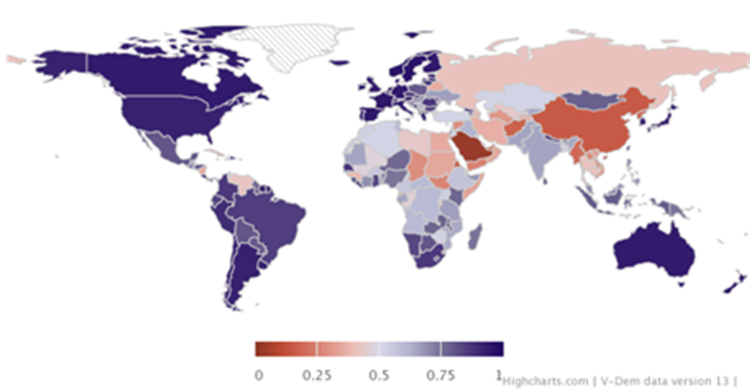

While the overall trend is perhaps better than expected, we need to concede that the glass is only half-full at best. A “feel-good narrative” would be dangerous (Wadongo 2014). We count only ten cases in which merely “electoral democracy” – a lesser form of democracy where, typically, all possible liberties are only partially present – has proved more or less stable since its introduction in the early 1990s. A 2022 snapshot (Figure 2 below) shows that this concerns countries in West Africa such as Ghana and states in Southern Africa like Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. The remaining electoral democracies are largely small island states like Cabo Verde and Mauritius. A roughly equal number of countries must be considered hard autocracies. The worst examples represent the quasi-totalitarian states Equatorial Guinea and Eritrea. Other such dictatorships include Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, and the absolute monarchy of Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland). At the time of writing, countries like Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger must be considered military regimes – with civilian governments having been overthrown in coups in each.

Figure 1. Democratic Trends in Africa Over Time in Comparative Perspective

Source: Varieties of Democracy (2023).

Notes: Polyarchy is a concept of “real world” democracy (Dahl 1998) that includes free and fair elections as well as freedom rights close to liberal democracy. The numbers on the y-axis represent the average democracy score (with 1 being the most and 0 being the least democratic) across all countries in the respective world region.

The majority of African countries, however, qualify as “hybrid” regimes that are neither fully democratic nor entirely hard authoritarian. Hybrid regimes are those political systems that regularly hold elections but in which either voting polls themselves or governing practices do not fully conform to democratic principles. One can further differentiate between two groups within hybrid regimes. One comprises countries like Mauritania and Togo that lean more towards authoritarian rule. The Bertelsmann Transformation Index (2022) calls such regimes “moderate autocracies.” A second group encompasses cases closer to democracy, and hence can be labelled “defective democracies.” Countries like Senegal or Sierra Leone arguably belong to this group. Kenya, Malawi, and especially Zambia can also be considered democratic hopefuls, if not already electoral democracies, as recent elections were relatively free and fair in all three.

“Failed states” may form a final regime type, in which the government lacks control over its territory and the state hardly functions otherwise. Examples are Central African Republic, Somalia, and South Sudan, as well as arguably the Democratic Republic of Congo. Many Sahelian states like Mali are also showing signs of state failure.

Figure 2 also reveals regional patterns within sub-Saharan Africa. Democracy is most established in Southern Africa, while Central Africa has seen the least progress hereon. East Africa features many hybrid regimes. West African countries experienced substantial democratic progress in the past but have since suffered from a number of setbacks – not least in the Sahel, as the recent coups demonstrate. It is also worthwhile to look beyond the sub-Saharan Africa region. Figure 1 above also shows that the latter remains below the global average on democratic progress. Yet, sub-Saharan Africa compares favourably to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the world region seeing the lowest level of democracy. This is remarkable, not least because the general level of socio-economic development is on average higher in the MENA.

Figure 2. Level of Democracy (Polyarchy) in 2022

Source: Varieties of Democracy (2023).

Note: A darker shade of blue indicates the greater presence of democracy.

What Do Africans Want?

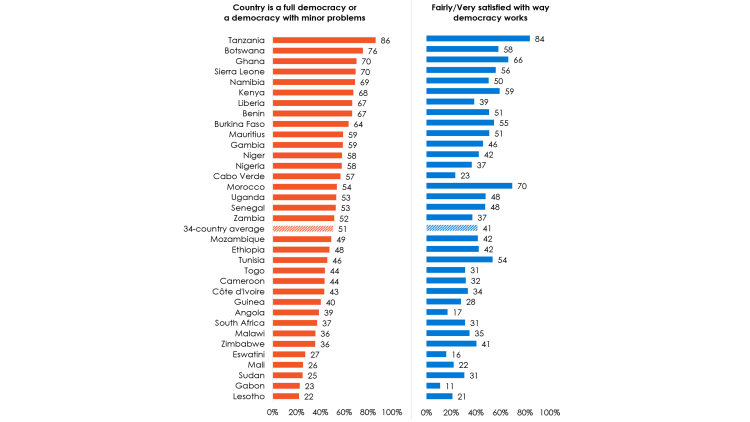

Usually, expert knowledge gathered in the Global North forms the basis of such assessments. While most democracy indices increasingly include African experts, they still rely heavily on Western expertise and do not sufficiently consider the views and attitudes of Africans themselves. However, Afrobarometer (2023) data fills this gap by providing information on citizens’ attitudes towards and perceptions of democracy and governance for up to 39 countries on the continent. The most recent full round of the survey covers the years 2019 to 2021. Findings indicate that Africans are largely committed to the idea of democracy and reject authoritarian alternatives. Yet, they find the “supply of democracy” – that is, the extent to which it is realised – to be largely lacking. On average, 51 per cent of respondents view their country’s political system as a democracy with no or minor problems while only 41 per cent are fully happy with how democracy works there.

These public views should, of course, be related to individual countries. Afrobarometer shows that, by and large, citizens’ perceptions of how democratic or not their countries are mirror expert ratings. This is true for both democratic showcases like Botswana and Ghana as well as for authoritarian countries like Gabon, Mali (after the coup), Sudan, and Zimbabwe. However, there are some noteworthy differences. Tanzania tops public qualification as a democracy (86 per cent of respondents there) but ranks as a defective democracy in expert assessments at best. In turn, only 37 per cent of South African respondents view their country as democratic – a remarkable deviation from its high score vis-à-vis all democracy indices used in expert assessments.

Figure 3. Afrobarometer’s Findings on the Extent of Satisfaction with Democracy

Source: Afrobarometer (2023).

Note: Respondents were asked: In your opinion, how much of a democracy is [your country] today? Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [your country]?

Viewing one’s country as democratic and preferring democracy are not the same thing. Afrobarometer finds solid popular support for democracy. On average two-thirds of all Africans prefer democracy as a system of government. They also reject authoritarian alternatives by a significant margin. Some 74 per cent reject military rule, 77 per cent reject one-party rule, and 82 per cent even reject one-person rule (Afrobarometer 2023: 6). While the preference for democracy has slightly decreased – in cases such as South Africa, even steeply – the support for presidential term limits (77 per cent of respondents) has grown. Africans also overwhelmingly wish to see the realisation of other democratic principles such as presidential compliance with court decisions, multiparty polities, and leaders chosen ideally via elections (Afrobarometer 2023: 7).

The Case for Democracy in Africa

That Africans overwhelmingly prefer democracy – including specific aspects of it – and reject authoritarian alternatives already makes an independent case for this form of government in Africa. If we take African sovereignty seriously, we must respect and support Africans’ preference for democracy. There are additional supporting arguments here: Democracy is ethically superior to other forms of government if we take the meaning of the word literally. Democracy is the rule of the people. It means that the populace decide who governs them. Liberal democracy also includes several additional civil and political liberties.

Sometimes theorists argue that, in the sense of polyarchy or liberal democracy, this form of government is a purely Western import and alien to African culture. While a debate on how the “rule of the people” – which is what democracy means – must be adapted to local conditions is important, opponents of democracy in Africa (and elsewhere) face the necessity of making the case for why Africans should not enjoy the right to determine their leaders and should not enjoy civil liberties. In short, live free from oppression.

In addition, there might be functional reasons to prefer democracy over other forms of government. Fully democratic political systems can react to public discontent without resorting to violence; people can remove governments without bloodshed, as famously stated by Karl Popper (1945: 121–122). Democracy is a peaceful way of managing conflict and this is no small advantage – although one may argue that this gain materialises only when democracy is fully functioning.

It has also been claimed that democracy is better for socio-economic development, even though the relationship here is complex: introducing democracy does not directly lead to prosperity and well-being. However, there is a theoretical and an empirical argument backing the claim that democracy fosters socio-economic development. First, authoritarian leaders must make happy the small elite inner circle keeping them in power, while democratic leaders must please voters – which incentivises producing better economic policies for larger numbers of people (Bueno de Mesquita and Smith 2011). Second, the best-performing African countries in socio-economic terms, Botswana and Mauritius, are long-standing democracies. Authoritarian states showcasing development are rare in Africa. The frequently cited exception, Rwanda, has still to stand the litmus test of what happens once President Paul Kagame leaves office. Most other current or past African autocracies have a dismal record regarding socio-economic achievements.

Democracy’s Drivers and Obstacles

If we agree that democracy in Africa and for its citizens is desirable, we must grasp what helps promote democracy and what serves to hinder it. Researchers have named several essential and favourable conditions here (e.g. Dahl 1998: 145–165): the level of socio-economic development, peaceful relations between “cultural” identity groups, the reining in of the military and other “forces of coercion,” as well as the political culture (of the elites) and external factors such as domination by outside countries. These factors are all interrelated, but can be discussed individually.

First is socio-economic development, with higher levels hereof also making democracy more likely. The middle class are the traditional drivers and supporters of liberalisation and democracy. Where there is more wealth to distribute, competition is less fierce. There is reason for hope. Largely ignored by the public, African countries have made substantial progress in these regards (Basedau 2019). At the same time, risks persist in the form a possible debt crisis, the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, or the global repercussions from the Russian war on Ukraine or from climate change.

Distributional conflicts often manifest along ethnic or other identity-group lines. Colonialism has left Africa with ethnically heterogenous populations and frequently saw divide-and-rule policies employed. Many sub-Saharan countries must cope with inter-ethnic and other identity-related conflicts. While diversity sadly always carries the risk of division, violent conflict is not inevitable. There are workarounds. Democracy, as an institutionalised way to peacefully manage tensions, and special fixes provided by “institutional engineering” can accommodate conflict risks: such examples might be federalism and decentralisation, or electoral systems that ensure representation and incentivise cooperation. Constraints on executive power such as term limits or regional quotas for presidential and other elections may help, too. A functioning democracy remains, however, not only a matter of institutional design but also of wise governance.

Democracy also requires that the “forces of coercion” remain under strict civilian control. Armed non-state actors threaten democratic rule. Moreover, the state security sector is one of the most eminent threats to democracy. The recent military coups in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Niger, and Sudan attest to this challenge (in Gabon, an authoritarian regime was overthrown). Yet, such coups do not come out of the blue. Typically, they occur in countries with a traditionally politicised military and a manifest political or other crisis – which also explains why those leading coups are often quite popular, given that they promise to address the sources of widespread dissatisfaction in terms of socio-economic and/or security problems.

Coup-triggering crises are often related to the perception that incumbents have failed to address core challenges. Political and other elites are key to the success of democracy. Dahl (1998) named pro-democratic political culture as an essential condition for democracy, meaning attitudes towards it on the part of both the population and of leaders. As discussed above, it is not the lack of popular support for democracy in Africa but rather the ever-present temptation of authoritarian rule for elites that threatens it. Elections entail the possibility of losing power. The relationship between elite attitudes towards democracy and its success seems obvious. We must, therefore, ask how elites can either become (more) democratic and/or adhere better to the rules of the game. One fix is the institutional constraints imposed by elections or term limits. Another is a vibrant civil society that monitors and keeps in check any authoritarian tendencies.

However, external influences will make a difference too. Dahl (1998) saw the biggest external threat to democracy as lying in the domination by outside countries hostile to this form of government, like the Soviet Union or other imperial powers. Even following formal decolonisation external influences still matter, and their impact might increase in a changing and potentially more confrontational world order. The good news is that competition at the global level and the increasing diversification of external actors in Africa such as Brazil, China, India, Middle Eastern countries, and Russia increases the choice regarding external partners and thus the agency of African leaders. Yet, this may also increase the agency of leaders vis-à-vis their populations. If nefarious African elites gain outside support, they also gain greater leverage over their populations.

The growing influence of authoritarian countries like China might also serve to promote non-democratic role models. Russia has been successful in spreading the narrative that democracy is a Western import rather than a system of government of self-rule. Middle Eastern countries have also been active in promoting Islamism, which may have provided fertile ground for the “jihadist wave” that has as of now befallen approximately one-third of sub-Saharan countries and is currently threatening West Africa.

There is also a looming danger at the systemic level. Growing “system competition” globally may degenerate into polarised thinking like during the Cold War. African leaders could then gain outside support regardless of their democratic credentials simply because of a pro-Western foreign policy or the supplying of strategic natural resources. In the worst-case scenario, global rivalries might fuel internal conflict and sustain or even intensify bloodshed, like in Angola or Mozambique before the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Foreign Policy Implications: The What, Who, and How

A Western policy (re)orientation towards Africa needs to acknowledge that democracy can only prevail there when it is realised by Africans themselves. While external factors matter, the influence of the West vis-à-vis Africa is generally limited and likely to further decrease. Westerners should not and cannot “save Africa” – a benevolent but highly paternalistic view. The times of a “civilising mission” are over. Yet, a less missionary perspective should not be mistaken as a case for being cynical about democracy in Africa. As noted, its citizens do want democracy.

A first related imperative for foreign policy actors refers to making up their minds about what role the promotion of democracy should even play, especially in relation to other policy goals such as navigating geopolitical competition, ensuring the supply of natural resources, managing migration flows, and combatting violent extremism. Any such conceptualisations must embrace the tensions between respective goals. Moreover, any (Africa) policy will be more effective the more coherent it is. This obviously relates to the “concert” of nations, but also to different government bodies within countries – not least in Germany.

Beyond the “what” and “who,” one needs to also rethink the “how.” While all of the conditions discussed above like socio-economic development, peaceful intergroup relations, or a professional military are a sound basis for the promotion of democracy, one needs to avoid any policies that harm democracy. These include support for authoritarian leaders in pursuit of short-sighted goals such as realising Western foreign policy ambitions or the supplying of strategic natural resources. Admittedly, that is easier said than done. As discussed, foreign policy actors must consider diverse goals at the same time. Not uncommonly, ones other than democracy matter greatly. Sometimes for good reason: the need to manage violent conflict or natural disasters occasionally requires tacit cooperation with authoritarian regimes.

Yet, wherever possible, democratic governments in Africa should enjoy preferential treatment. In authoritarian regimes, civil society can be supported. Germany’s political foundations – which are quite specific compared to other international actors also addressing issues of democratic governance on the African continent – at times enjoy greater leverage when it comes to highlighting certain issues regarding which diplomats must act with greater caution. Special attention needs to be given to the most suitable narrative to “promote” democracy: it means the rule of the people, and thus self-determination. The case can hardly be made that Africans should be denied freedom from oppression.

At the same time, the chosen messaging must avoid paternalistic attitudes that play into the narrative of democracy being a Western imposition. Respectful “eye level” communication is not something granted by “donors” but a matter of attitude. One must increase efforts to counter the disinformation campaigns and anti-Western narratives of Russia and others. These attempts at redress will be more credible when Westerners critically reflect on their own courses of action hitherto. All too often, Western governments have earned a reputation for being hypocritical, paying only lip service to democracy, but actually prioritising less noble causes in Africa such as resource extraction or a pro-Western foreign policy. It seems advisable to be open about self-interest and tensions between goals, rather than preaching water and drinking wine. Yet, a consistent and persistent pro-democratic Africa policy will likely pay off: in being able to draw on popular support, it may well succeed in the long run.

Footnotes

References

Afrobarometer Network (2023), Africans Want More Democracy, But Their Leaders Still Aren’t Listening, Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 85, January, accessed 31 August 2023.

Arriola, Leonardo R., Lise Rakner, and Nicolas van de Walle (eds) (2022), Democratic Backsliding in Africa? Autocratization, Resilience and Contention, New York: Oxford University Press.

Basedau, Matthias (2019), Der unbemerkte Fortschritt: Ein Plädoyer für mehr “Afropositivismus”, GIGA Focus Africa, 2, March, accessed 31 August 2023.

Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) (2020), The Transformation Index, accessed 18 May 2023.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith (2011), The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics, New York et al.: Public Affairs.

Dahl, Robert A. (1998), On Democracy, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Popper, Karl (1945), The Open Society and Its Enemies, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Varieties of Democracy Project (2023), Graphing Tools, accessed 31 August 2023.

Wadongo, Evans (2014), Africa Rising? Let’s be Afro-Realistic, in: The Guardian, 7 November, accessed 28 December 2018.

Editor GIGA Focus Africa

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Africa

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Basedau, Matthias (2023), Under Pressure: Democratisation Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa, GIGA Focus Africa, 4, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfaf-23042

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.