- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The War in Ukraine and Latin America: Reluctant Support

GIGA Focus Latin America

The War in Ukraine and Latin America: Reluctant Support

Number 2 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3573

The War in Ukraine has highlighted the divisions within and between Latin American countries. Although the Russian invasion of Ukraine goes against international norms endorsed by Latin American countries, the conflict seems remote and evokes long-standing rejection of United States policies. Notably, both regional powers, Mexico and Brazil, were reluctant to join the Western condemnation of Russia.

Both the left-leaning Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador as well as Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro have maintained the traditional position of autonomy and neutrality that has characterised their countries’ diplomatic histories.

The Russian argument that NATO went too far in penetrating its security perimeter finds broad echo in Latin America. Paradoxically, such realist reasoning accepts the old geopolitical theory of great powers’ “spheres of influence,” which contradicts the autonomist theories historically endorsed by Latin American governments vis-à-vis US power.

The war, and especially the sanctions on Russian hydrocarbons, have triggered fuel-price hikes, stimulated a rapprochement of the US with Venezuela, and altered the latter’s tense relationship with neighbouring Colombia, easing conditions for the restoration of bilateral relations.

Policy Implications

Those interested in maintaining relations with Latin America should take note of the divide among the region’s governments, many showing only reluctant support for the West’s anti-Vladimir Putin policies. The insistence on foreign policy autonomy here cannot be understood as an articulated regional project but rather serves as a discursive framework which allows each government international room for manoeuvre, favouring relations with multiple external actors.

The War has Reaffirmed Well-Known Divides

As in much of the Global South, the War in Ukraine has caught the attention of governments and societies in Latin America too. The impact of a conventional war of such magnitude and the direct and indirect involvement of great military powers has put the region on alert. However, the remoteness of the conflict, the political differences resulting in polarisation, and pressing domestic issues have generated diverse reactions and a widespread lack of interest in the causes and development of the war.

Since it is difficult to pigeonhole societies, we must look at government decisions to elucidate national positions on the war. The first global multilateral reaction to the war was the United Nations General Assembly Resolution of 3 March 2022. This received majority support with abstentions by 35 states, including four Latin American ones: Bolivia, Cuba, El Salvador, and Nicaragua (it could have been five as Venezuela maintains a very close relationship with Moscow; however, the country cannot vote at the UN as it is still suspended for non-payment to the organisation).

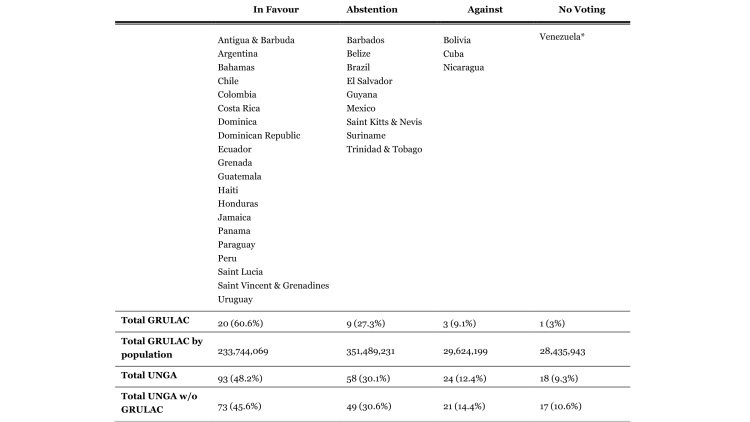

However, the boldest official positions were shown later in the vote on 7 April, when the UNGA decided to suspend Russia from the UN Human Rights Council. In this, we find three different groupings: of the 33 members of the Group of Latin America and the Caribbean (GRULAC), 20 voted in favour of the motion, nine abstained, three voted against (Venezuela again could not vote) (see Table 1 below). This vote is widely considered the most obvious indicator of the official position of the respective governments on the War in Ukraine, and especially towards Russia.

Table 1. UNGA Votes to Suspend Russia’s Membership in the UNHRC – Latin America and the Caribbean States

Source: United Nations 2022.

Note: * Suspended due to lack of UN membership payment, but explicitly Russia’s supporter.

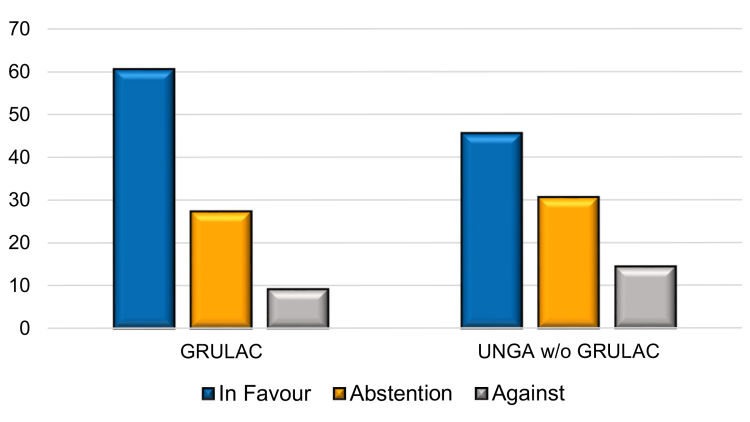

A closer look shows that in terms of votes in favour, Latin America and the Caribbean exceeds the rest of the world – including the NATO powers and their closest allies – by 15 percentage points. For abstentions, the difference is 3.3 per cent less than for the rest of the UN member states. Regarding votes against, GRULAC is also below average with 5.3 per cent fewer votes than the rest of the world (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. The Latin American and the Caribbean Group and the Rest of the UNGA Voting

Source: United Nations 2022.

The data confirms two Latin American facts: the external behaviour of the region is more complex than generally believed, and it is in a phase of marked divisions between governments. This is evident when contrasting those who have reacted against Moscow versus those who have sided with it. Despite the differences, as a general rule, this heterogeneity in political response has its roots in matters of domestic politics. Thus, the countries with which Vladimir Putin’s Russia has built the best relations are those whose regimes are among the most authoritarian in the region and the most opposed to Western institutions, practices, and policies. These relations are more political than economic since Russia barely exported 1.55 per cent of its products to Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020. Of this, 0.27 and 0.22 per cent corresponded to the markets of Bolivia and Nicaragua respectively, while exports to Cuba and Venezuela were even lower besides (Observatory of Economic Complexity 2022).

Those governments that condemned the “special military operation” are a much larger and more diverse grouping meanwhile. Among them are countries with high rates of democracy and individual freedoms, such as Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay. Also, the only NATO global partner in the region, Colombia – whose support, along with also Argentina’s backing, means two of the United States’ Latin American three “major non-NATO allies” are on-board. These countries are characterised not only by having better relations with the West, especially with the US, but with a better democratic performance too.

However, despite the official government alignments, the unofficial reactions are striking. Two notable cases are Argentina and Venezuela. In the days that followed the vote on 7 April, the hashtags #PerdónRusia and #PerdónPutin (#SorryRussia and #SorryPutin) trended on Twitter, triggering an angry debate about what the position of Buenos Aires should have been before the invasion of Ukraine. The Argentine president, Alberto Fernández, visited Putin on 3 February, three weeks before the invasion, and offered to be Russia’s “gateway to Latin America” – which is remarkable. This ambivalence received a mixed reaction from Argentine society, at least as reflected on social media networks (Notired 2022). Conversely, Venezuela’s “interim president” Juan Guaidó, formally recognized as legitimate by most of the West, holds a position against Putin’s Russia – an important partner for Nicolás Maduro.

There are two types of governments that stand out from those that abstained: small states and regional powers. The latter deserve separate treatment and will be dealt with in the next section. In the first group are six of the 15 full members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) – Barbados, Belize, Guyana, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago – plus the Central American state of El Salvador. In the case of CARICOM, its division is striking. However, this does not imply a rupture in the fundamental agreements of the organisation’s overarching strategy since it tends to cooperate to create platforms of bargaining power in the international arena. Recent studies show that the external incentives that these CARICOM states have received from hemispheric and Caribbean powers, such as the US and Venezuela, have not been enough to undermine their desire for autonomy. As such, it would be inaccurate to think that they simply vote together in crucial aspects of world politics.

Meanwhile, El Salvador has become a focus of attention for its heterodox authoritarian drift under President Nayib Bukele. His government has tried to maintain political equidistance in international security matters. It is unclear whether this is due to an autonomous aspiration, empathy with the Russian authoritarian government, or mere disinterest in world affairs.

The Russian Invasion and the Regional Powers’ Neutrality

The second group of abstentionists is remarkable. It comprises the two largest Latin American powers, Brazil and Mexico, who paradoxically have ideologically opposed governments. Regarding the War in Ukraine, the foreign policy positions of the Jair Bolsonaro and Andrés Manuel López Obrador governments have been to adhere to the doctrine of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states to ensure an aura of international autonomy. This has been the historical position of both countries, and in recent research and works of dissemination Latin American scholars have highlighted it being part of a long tradition of Latin American republicanism (Long and Schulz 2021; Rodríguez 2022), of adherence to regional legal traditions (Sanahuja, Stefanoni and Verdes-Montenegro 2022), and an aspect also of a regional response to a changing and geopolitically uncertain world (González Levaggi and Albertoni 2022; Pitts 2022).

As already mentioned, Brazil and Mexico are the two current Latin American and Caribbean members of the UN Security Council, meaning they can maintain and strengthen a position of equidistance from the conflict. However, this does not reflect the interest of the majority of the states in the region. Moreover, Bolsonaro was, aside from Argentine president Fernández, the other Latin American head of state to recently visit the Kremlin. That meeting, on 16 February, was just over a week before the start of the invasion. Furthermore, even in recent days, President Bolsonaro has reaffirmed his country’s neutrality and asserted that he has no intention of affecting Brazil’s business with Russia (El Economista 2022). López Obrador has been less vocal but more forceful in the Mexican case, affirming that his country “is not a colony of Russia, or China, or the United States” (El País 2022).

These positions would be expected since a power like Brazil has continued to play the autonomy card as an essential part of its grand strategy while Mexico, in turn, has been a champion of non-intervention through its traditional “Estrada Doctrine”. However, autonomy and non-intervention are open to interpretation. In the case of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some Latin American arguments aimed at questioning NATO’s expansion to the east are close to the offensive realist thesis of the American scholar John Mearsheimer (2014). According to this, the West and Ukraine itself is responsible for having encouraged a military reaction by Russia in the face of the threat posed to its sphere of influence and the security of its borders. This has transcended social media debate in Latin America to also become an argument made by relevant political leaders, including some who do not represent governments. For example, one of the tweets with the greatest reach by the Latin American branch of the official media outlet Russia Today, the highly influential RT en Español, reproduces Mearsheimer’s argument in Spanish – with it finding a significant reception in the Spanish-speaking Twittersphere (Alliance for Securing Democracy 2022). Another example comes from Bolsonaro’s main opponent and ideological rival, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva. Without direct reference to Mearsheimer, but following his spirit, Lula – who could return to the Brazilian presidency in January 2023 – said in an interview with Time magazine in May 2022 that:

We politicians reap what we sow. If I sow fraternity, solidarity, harmony, I’ll reap good things. If I sow discord, I’ll reap quarrels. Putin shouldn’t have invaded Ukraine. But it’s not just Putin who is guilty. The US and the [European Union] are also guilty. What was the reason for the Ukraine invasion? NATO? Then the US and Europe should have said: ‘Ukraine won’t join NATO.’ That would have solved the problem.

And he added:

[…] sometimes I sit and watch the President of Ukraine speaking on television, being applauded, getting a standing ovation by all the [European] parliamentarians. This guy is as responsible as Putin for the war. Because in the war, there’s not just one person guilty. (Time 2022)

The official position of the Brazilian and Mexican presidents and a regionally influential leader like Lula denote that the two major Latin American powers follow the path of autonomy by way of neutrality. The War in Ukraine seems to them to be a European – or, at most, a North Atlantic – affair, and they prefer to keep their distance from it. However, a paradox appears, and it is that in this realist reasoning there is justification given for the old geopolitical theory of the spheres of influence. When it is claimed that NATO went too far in penetrating Russia’s security perimeter, it asserts that the great powers enjoy geopolitical prerogatives in their “near abroad.” This could not be more contrary to the autonomist theories, the rationality behind the historical Latin American international political behaviour – especially when facing up to US power. After all, why should Ukrainian autonomy aspirations be less legitimate – or less dangerous – than Latin American ones?

By taking a comparative and expanded perspective on the situation, it is possible to detect flaws in the logic of the Brazilian and Mexican leaders. The at least partial opposition to the West by the Brazilian and Mexican governments and leaders shows that perhaps the general principles of the Latin American diplomatic tradition can be helpful, but maybe as an ideological cover to justify opposition to values that could undermine their powers within and beyond their countries. Arguments about autonomy as a grand strategy, international legalism, or republicanism as a substratum of diplomatic action are helpful general approaches. However, we cannot lose sight of the fact that populist foreign policy plays an important role here. When it comes to foreign policy, populists base their arguments on external threats to the people. Just as national elites would undermine the power of the people, international elites would diminish their room for manoeuvre (Destradi, Plagemann, and Taş 2022).

The Distant Crisis Is Shifting a Neighbouring Relationship

For over 20 years now, Colombia and Venezuela have been opponents. Their tensions have been cyclical, encouraged from the beginning by the decision of the Colombian elites in favour of a closer relationship with the US – especially since “Plan Colombia” – and the change of powerbrokers and political regime in Venezuela by the Hugo Chávez-led “Bolivarian Revolution.” In recent years, the heirs of Uribismo and Chavismo, Iván Duque and Nicolás Maduro, have staged a hostile antagonism. Recently, the Venezuelan economy collapsed, and Colombia became home to most Venezuelan migrants in the space of just a few years. Meanwhile, the Duque government received and tried to protect and integrate these migrants, recognised and supported the interim government of Guaidó, and led a “diplomatic siege” against Maduro’s regime as strongly instigated by the Donald Trump administration. Adding to the historical tensions between these neighbours is the fact that since 2006 Venezuela has been the main buyer of Russian arms in Latin America, occupying sixth place worldwide. For its part, Colombia, in 2018, became the first and only global partner of NATO in the region and, in 2022, a major non-NATO ally of Washington.

In light of the preceding developments, it is natural that the positions of Bogotá and Caracas are opposing ones. Although, due to being suspended for payment non-compliance, Venezuela was unable, as noted, to vote in the UNGA on Russia’s suspension from the UNHRC, the position of the Maduro government has been one of public and firm support for Moscow’s narrative. The Russian ambassador to Caracas, Sergey Melik-Bagdasarov, has participated in various events and rallies. The ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela has organised demonstrations supporting Russia. Moreover, in a recent diplomatic decision, Maduro appointed Carlos Faria as his new foreign minister, who previously served as the Venezuelan ambassador to Moscow. Russia has offered formidable support to the Bolivarian Revolution, especially diplomatically and through the sale of military technology. After the sanctions applied by the Trump administration, the Russian transport and financial infrastructures have served to help the diminished Venezuelan oil industry continue trading crude at a discount in unregulated markets. And not only was there a special personal relationship between Putin and Hugo Chávez, but between the Russian head of state and the latter’s successor, Maduro, too – not to mention between defence ministers Sergei Shoigu and Vladímir Padrino López.

However, important changes resulting from the war have appeared on the horizon. In the wake of sanctions on Russian hydrocarbons, which are expected to escalate and take crude and natural gas out of Western markets, the US economy is seeing rising fuel prices. This is occurring at a particularly adverse moment for the Joe Biden administration, since his presidency has low popularity ratings and mid-term elections are coming up in November. The impact of rising fuel prices led even more conservative American opinion-makers to emphasise that the most realistic thing to do was to reduce tensions with Venezuela, lift oil sanctions, and reactivate trade in the name of American energy security (Regan 2022). The first attempts took place a little less than two weeks after the Russian invasion, when a delegation, led by the US diplomatic chief for Venezuela, James Story, who, due to tensions, had located his operations in Bogotá, travelled to Caracas and met with Maduro delegates at the seat of the Venezuelan government, the Miraflores Palace.

It is important to note that leading oil experts have pointed out that expecting Venezuela to compensate for declining Russian supplies in international energy markets would be to believe in a mirage. Indeed, once powerful in the Western Hemisphere, the Venezuelan oil industry has declined enormously due to the politicisation Chavismo subjected it to. By turning it into the petty-cash generator for the Revolution, Chávez condemned the state-owned PDVSA and indeed the economy of the entire Venezuelan petrostate. However, with the help of Iranian partners and the Russians themselves, Venezuela has been reactivating its production. Yielding about 700,000 barrels of oil daily, Venezuela is close to Colombian production, which reaches about 750,000 itself. The difference, however, is that these values are in the low range for Venezuelan output and the high range for Colombia, and that in terms of Venezuelan crude reserves they are 150 times bigger than those of Colombia (Trading Economics 2022).

In parallel, Chavismo under Maduro has expressed an interest in economic opening, although with a questionable framework regarding the (defective) rule of law. However, this has not limited the country’s and PDVSA’s bondholders from being compensated in a timely manner; meanwhile, foreign oil companies – among which the American Chevron stands out – continue to operate in the country with the fragile but continuous legal certainty granted a predator. Colombia’s oil industry, in contrast, has a more solid legal and institutional basis. Still, it also has strong social and environmental movements that advocate stopping oil exploration and which have managed to stop the most important pilot trials for fracking.

The rapprochement between Washington and Caracas came before the war. In September 2021, there was an attempt to establish a dialogue table between the Venezuelan government and the opposition in Mexico under the auspices of Norway. From the beginning, it was known that the opposition had the backing of the US and that the Colombian government of Duque was aware of it. Nevertheless, these pragmatic approaches motivated by geopolitics and energy security issues following the War in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia were not discussed with Bogotá. In a realistic manoeuvre of pure and simple national interest, the Biden administration privileged direct contact with the Maduro government – leaving out the one country which most strongly supported the diplomatic siege and, indeed, absorbed the greatest impact from Venezuelan out-migration.

This embarrassing situation occurs amid an electoral campaign for the presidency of Colombia in which the left-wing candidate, Gustavo Petro. Petro, an experienced politician who began his public life in the urban guerrilla movement of M-19, is the clearest antagonist of Uribismo. His position in foreign policy, long before the War in Ukraine, had been to re-establish relations with Maduro’s Venezuela. In addition, the other candidate, Rodolfo Hernández, a populist without a clear ideological identity, affirmed that among his first diplomatic decisions would be to reinstate the ambassadors and consuls in Colombia and Venezuela. The effects of the war have not changed that, but these new circumstances have supported those decisions at least – making it clear that the Colombian government was left alone in the failed manoeuvre to isolate the Maduro regime.

In sum, Latin American reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine are far from being homogeneous or even completely coherent. While most of the region has tended to condemn Russia, Moscow continues to have regional supporters based on affinities between authoritarian regimes. In addition, the two largest regional powers, Brazil and Mexico, have bowed to neutrality under arguments of moral relativism that, although disguised as an autonomist doctrine of foreign policy, end up being contradictory to societies and governments that have historically opposed regional hegemonic impositions. Finally, sanctions against Russia are unintendedly helping to counter Venezuela’s partial regional isolation in the face of the US’s energy-security needs, opening a new round of formal and informal negotiations on the status quo in the Caribbean basin.

Footnotes

References

Alliance for Securing Democracy (2022), Hamilton 2.0 Dashboard, accessed 1 May 2022.

Destradi, Sandra, Johannes Plagemann, and Hakkı Taş (2022), Populism and the Politicisation of Foreign Policy, in: The British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

El Economista (2022), Brasil no le suelta la mano a Rusia, accessed 1 May 2022.

El País (2022), López Obrador afirma que México “no es colonia de Rusia, ni de China, ni de EE UU”, accessed 8 May 2022.

González Levaggi, Ariel, and Nicolás Albertoni (2022), Latin America Reacts to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine, CARI: Serie de Artículos y Testimonios, 165, accessed 8 May 2022.

Long, Tom, and Carsten-Andreas Schulz (2021), Republican Internationalism: The Nineteenth-Century Roots of Latin American Contributions to International Order, in: Cambridge Review of International Affairs.

Mearsheimer, John J. (2014), Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions that Provoked Putin, in: Foreign Affairs, 93, 5, 77–89, accessed 16 June 2022.

Notired (2022), #PerdonRusia: la tendencia que explotó en las redes tras la polémica votación argentina en la ONU, accessed 25 April 2022.

Observatory of Economic Complexity (2022), Where Does Russia Exports to? (2020), accessed 5 April 2022.

Regan, Trish (2022), Trish Calls For Opening Up of Venezuela, accessed 1 May 2022.

Rodríguez, J. Luis (2022), Explaining Latin America’s Contradictory Reactions to the War in Ukraine, accessed 1 May 2022.

Sanahuja, José Antonio, Pablo Stefanoni, and Francisco J. Verdes-Montenegro (2022), América Latina frente al 24-F ucraniano: entre la tradición diplomática y las tensiones políticas, in: Fundación Carolina: Documentos de Trabajo, 62, accessed 8 May 2022.

Pitts, Bryan (2022), Latin America and the New Non-Aligned Movement, accessed 8 May 2022.

Time (2022), Lula Talks to TIME About Ukraine, Bolsonaro, and Brazil’s Fragile Democracy, accessed 9 May 2022.

Trading Economics (2022), Crude Oil Production, accessed 5 April 2022.

United Nations (2022), UN General Assembly Votes to Suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council, accessed 5 April 2022.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

How to cite this article

Mijares, Victor (2022), The War in Ukraine and Latin America: Reluctant Support, GIGA Focus Latin America, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-22022

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.