- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Easier In Than Out: The Protracted Process of Ending Sanctions

GIGA Focus Global

Einfacher zu verhängen als aufzuheben: Die langwierige Beendigung von Sanktionen

Nummer 5 | 2019 | ISSN: 1862-3581

Seit dem Ende des Kalten Krieges ist nicht nur die Verhängung, sondern auch die Aufhebung von Sanktionen zu einem allgegenwärtigen Phänomen in der internationalen Politik avanciert. Von insgesamt 292 Fällen seit dem Jahr 1990 wurden ungefähr 85 Prozent bis zum Jahr 2018 beendet. Vermeintlich erfolglose Sanktionen – wie die EU Maßnahmen gegen Russland – haben zu intensiven Diskussionen über eine mögliche Aufhebung geführt.

Weniger als die Hälfte aller Sanktionen enden durch Zugeständnisse des sanktionierten Regimes. Ein Beispiel hierfür sind die Sanktionen gegen den Iran wegen des Atomprogramms, die aufgehoben wurden, nachdem Teheran Begrenzungen bei der Anreicherung von Uran und regelmäßigen Kontrollen zustimmte. Im Gegensatz dazu nahm die EU die Entwicklungshilfe mit dem Sudan wieder auf, obwohl das Regime noch immer für seine Menschenrechtsverletzungen bekannt war. Entscheidungsträger sind regelmäßig mit der Frage konfrontiert, ob sie bisher erfolglose Sanktionen aufrechterhalten oder „kapitulieren“ und sie aufheben sollen.

Diese Entscheidungen werden nicht nur auf der Grundlage rationaler Kosten-Nutzen-Rechnungen getroffen. Die Beendigung von Sanktionen ist vielmehr ein volatiler und oftmals uneindeutiger Prozess, der von den Interaktionen zwischen Sanktionssendern und sanktionierten Staaten sowie ihren unterschiedlichen Handlungslogiken beeinflusst wird. Die Aufhebung von Sanktionen beendet auch die internationale Isolation des ehemals sanktionierten Staates. Ein solches Signal kann extrem umstritten sein, wie Kontroversen über die Lockerung von US-Sanktionen gegen Kuba zeigten.

Bei der Verhängung von Sanktionen getroffene Entscheidungen beeinflussen die Aufhebung. Einige Sanktionsregime beinhalten Überprüfungsvorschriften, Verfallsklauseln und klare Ziele, was eine regelmäßige Kontrolle ihrer politischen Zweckmäßigkeit erleichtert.

Fazit

Es ist leichter Sanktionen zu verhängen als diese aufzuheben. Erfolglose Sanktionen stellen Entscheidungsträger vor ein Dilemma: Die Beendigung solcher Maßnahmen, obwohl die Ziele nicht erreicht wurden, kann die Reputation der Senderstaaten beschädigen. Die Fortsetzung von Handels- oder Finanzrestriktionen ist aber ebenfalls kostspielig. Eine graduelle Aufhebung der Maßnahmen mit Hilfe klarer und realisierbarer Etappenziele kann Anreize für schrittweise Zugeständnisse der sanktionierten Staaten schaffen.

A Neglected Dilemma

Since the end of the Cold War, sanctions have become one of the most popular foreign policy instruments for addressing violent conflict, electoral misconduct, human rights abuses, and authoritarian rule. The measures employed have ranged from relatively targeted ones like asset freezes and travel bans to diplomatic or financial sanctions and commodity embargoes. Novel data collected by GIGA researchers on the European Union, the United Nations, the United States, and on regional organisations (ROs) shows that these international actors have initiated more than 290 international sanctions targeting some 109 different countries (Attia and Grauvogel 2019). This data covers all sanctions imposed by these key international senders between 1990 and 2015, as well as ones that were imposed prior to the end of the Cold War but continued to persist thereafter.

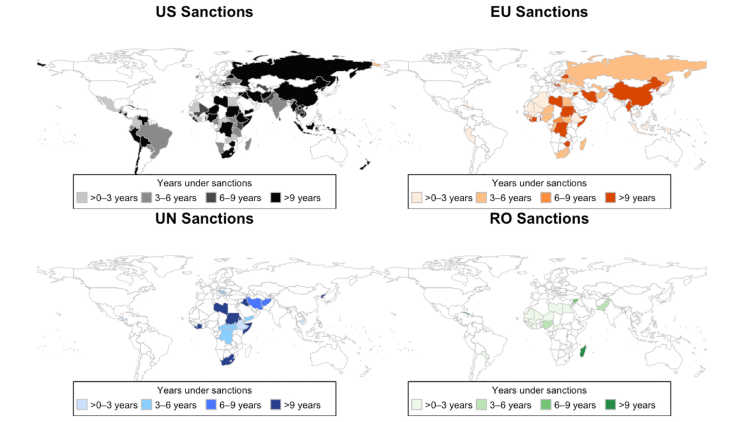

The US initiated 150 cases, which makes it the world’s leading sanctions sender. In 2003 alone, for example, the US imposed sanctions against more than 35 countries, many of which were unusual targets in the sense of being economically prosperous democracies – with the measures imposed so as to coerce them into formally granting immunity to American citizens in front of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The EU (with 75 cases) and the UN (32 cases) make less frequent use of sanctions, not least because their decisions require more complicated coordination among respective member states. Sanctions senders not only differ in terms of the frequency of their sanctioning activity but also regarding the duration and geographic scope thereof (see Figure 1 above). While the US and UN impose sanctions with the highest average durations of eight and seven years respectively, measures implemented by the EU and by ROs are on average already removed after six and five years respectively – inter alia, because many of their coup-related sanctions are short-lived. Moreover, the US is relatively active in its “backyard,” Latin America, whereas UN sanctions – most of which are conflict-related – and EU sanctions – which oftentimes address governance issues – primarily target the African continent, as well as the Middle East and Asia to a certain extent.

The basic idea behind sanctions is to interrupt the ordinary diplomatic, trade, and financial relations between sanctions senders and their targets until the latter change their objectionable behaviour. The African Union, for example, terminated its diplomatic sanctions imposed on Côte d’Ivoire in 2011 after democratic elections were held in November 2010. Likewise, all nuclear-related sanctions imposed by the EU, UN, and US on Iran ended with the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, under the terms of which the regime in Tehran agreed to eliminate its stockpile of medium-enriched uranium and to allow regular inspections. However, only less than half of all sanctions cases are terminated because the targeted regime has made meaningful concessions. The US, for instance, has lifted various financial and travel restrictions against Cuba since 2014 even though the original goal of forcing the socialist republic to adopt a representative democracy has not been achieved. Similarly, European sanctions against Sudan ended without any significant behavioural change on the part of that country’s government. In 2002 the EU resumed development aid to Khartoum, which had been suspended after Omar al-Bashir’s coup in 1989 – even though the regime remained notorious for its human rights violations and infringement of political liberties.

The termination of sanctions sends a signal that the formerly targeted regime will be reintegrated into the international community. Unsuccessful sanctions hence constitute a policy dilemma. Lifting them despite the failure to achieve stated goals is problematic. According to Cuban pro-democracy advocates, the removal of certain restrictions against the regime in Havana jeopardised human rights activism in the country (The Guardian 2016). However, the continuation of sanctions regardless of meagre chances of actual acquiescence also comes at a price. In the case of US sanctions against China following the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, US business associations lobbied against their continuation. Organisations such as the American Chamber of Commerce argued that the measures severely damaged US industries.

While purportedly unsuccessful sanctions often spark intense political controversy about whether they should be lifted, few sanctions regimes are imposed with a clear road map for their removal. The Western sanctions against Russia are a case in point: the attainment of the originally stated goal, the reversal of the annexation of Crimea, appears unlikely, but no alternative strategy for ending these sanctions exists thus far. To design feasible road maps for the termination of sanctions, more precise knowledge about how, when, and why sanctions end is crucial, but research has largely focused on the implementation and effectiveness of sanctions to date.

Successful Sanctions End Quickly

Sanctions are more likely to succeed early on. If the targeted regimes do not expect that they can resist such external pressure, these governments tend to concede quickly because enduring sanctions would create unnecessary costs. Researchers have shown that governments even alter their objectionable behaviour at the mere threat of sanctions in such cases (Drezner 2003). Accordingly, some of the most successful sanctions end before they have even been implemented. Another example of short-lived measures that result in some degree of desired political change are sanctions imposed by the AU in response to coup d’états. The AU unequivocally condemns such unconstitutional changes of government and imposes sanctions – most notably, suspension of the respective country’s membership in the organisation – until constitutional order has been restored. These sanctions usually end quickly once political actors agree on a transition of power to civilian rule. Examples include the AU sanctions against Mauritania (2005–2007), Guinea (2008–2010), and Niger (2010–2011), none of which ultimately lasted for more than two years.

The more pressure the targeted governments face, the harder it is for them to resist the senders’ demands. The target’s compliance, in turn, hinges on their political and economic vulnerability, as well as on their ability to mobilise countermeasures. Many countries under sanctions engage in sanctions-busting activities, shielding them from potential costs (Early 2015). The aid provided by the Soviet Union and other countries of the Communist Bloc to Cuba in support of the Castro regime during the first two decades of US sanctions prominently illustrates this. If sanctions fail to extract meaningful concessions prior to or quickly after their imposition, two opposing developments tend to occur.

On the one hand, senders hold on to sanctions for several reasons. Sanctions are measures “between words and war” (Wallensteen and Staibano 2015), which makes their continuation less expensive than the maintenance of other foreign policy tools such as humanitarian interventions. While governments have to mandate and budget for military missions, sanctions’ costs accrue more indirectly. Nonetheless, senders invest certain resources in the imposition of sanctions, which are lost if the measures are lifted as long as the goal is not achieved. These so-called sunk costs motivate sanctioners to keep their measures in place (Bonetti 1994). Moreover, leaders of sender states face high political costs when they capitulate and remove sanctions without obtaining meaningful concessions if the sanctions garnered strong domestic support. US sanctions against Cuba followed precisely this logic, as the continuation of those measures was largely driven by domestic calls for action (Schreiber 1973).

On the other hand, governments abandon sanctions when the costs of keeping them in place exceed the benefits of achieving the original goals behind them. A change of the ruling coalition often leads to a re-evaluation of long-lasting sanctions’ costs and benefits, thus paving the way for their termination (Krustev and Morgan 2011). For instance, President Barack Obama lifted sanctions against 44 countries during his first few months in office, in 2009. These sanctions had been in place for more than six years, and had been initially imposed by the George W. Bush administration to target countries refusing to formally grant Americans immunity from the ICC. Moreover, sending nations experience “sanctions fatigue” (Elliott and Hufbauer 1999: 407) when the domestic costs of maintaining sanctions attract increased attention over time while the willingness to compromise economic opportunities for political reasons wanes.

The Signalling Dimension of Lifting Sanctions

Yet sanctions termination can fail to occur even if it makes sense from a – predominately economic – cost–benefit perspective. Recently, the Donald Trump administration reimposed restrictions on Iran and left the deal that had previously led to the termination of all nuclear- related sanctions even though the end of sanctions potentially offered business opportunities, and the agreement was in the “best interest of America’s security” as US Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken stressed to Congress (Blinken 2015). Three reasons account for the protracted nature of termination processes, which can follow different logics of action.

First, the Iran example shows that sanctions termination not only offers the possibility to restore economic ties but also constitutes a visible symbol for ending a target’s international isolation. Accordingly, President Trump did not see the removal of the Iran sanctions as a simple act of economic relief but also as a signal for the reintegration of a rogue state, which had to be prevented (Nephew 2018). The termination of sanctions signals rapprochement and a normalisation of bi- or multilateral relations (Grauvogel and Attia forthcoming). Such a symbolic act can be highly controversial, especially when sanctions end without target compliance.

Second, the termination of sanctions – especially long-lasting ones – is often a gradual, volatile, and even inconclusive process. With the increasingly common use of sanctions that target specific individuals and firms, the EU, UN, and US can remove people and companies from their so-called blacklists step-by-step. Beyond responding to political developments in the target state, such a process develops its own internal dynamics. The EU, for example, gradually reduced the number of Zimbabwean officials and companies subject to travel bans and asset freezes over a period of no less than four years between 2010 and 2014. During this period, different logics of action clashed: Belgium pushed for the removal of diamond companies from the blacklist due to its own commercial interests, and the Netherlands was in favour of rewarding modest political reforms in Zimbabwe, while the United Kingdom insisted on keeping sanctions in place to condemn continuing human rights abuses under President Robert Mugabe (Grauvogel and Attia forthcoming).

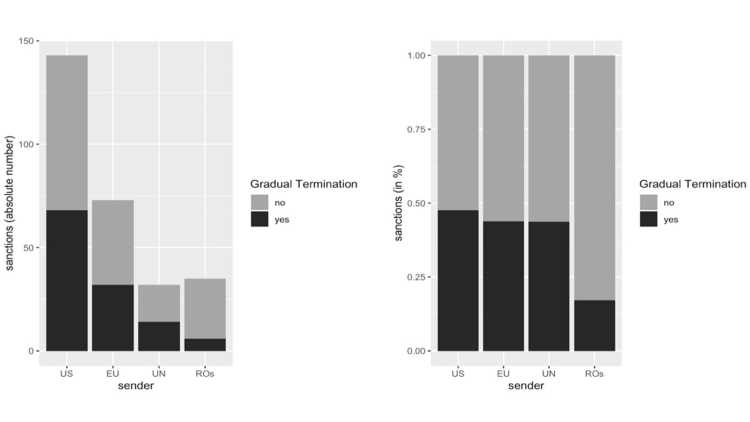

Despite such struggles among member states, researchers describe the EU as a “responsive sanctioner” (Luengo-Cabrera und Portela 2015: 1) that gradually lifts measures to incentivise targets’ compliance. Our data shows that the EU does not stand alone in this regard: Gradual removal is a common strategy pursued by sanctions senders in more than 43 per cent of the cases (see Figure 2 below). Examples include the termination of UN sanctions against Cote d’Ivoire and of US sanctions against Myanmar in 2016, where senders progressively lifted the measures in response to on-the-ground developments.

Third, sanctions termination is further complicated by the fact that not all senders impose and lift their restrictions at the same time. More than 50 of the 109 countries under sanction were targeted by multiple senders simultaneously. Yet, the different senders eventually lifted these sanctions in the same year in less than one-third of the cases. Sanctions removal by one sender thus significantly diverges from ending all restrictions imposed against the target for a large number of sanctions regimes. This a-synchronicity severely affects the signalling dimension of removing sanctions. In the case of Zimbabwe, the EU and US lifted sanctions at different paces. EU concessions did not constitute a clear step towards sanctions termination in light of continued US sanctions, because people in Zimbabwe “tend[ed] to mix up” the two senders’ measures.

Missing Piece of the Puzzle: The Design of Sanctions

While pleas for better coordination among sanctions senders are numerous (see, for example, Boucher and Clement 2016), there is another key piece to the puzzle of sanctions termination: their design, inscribed into the sanctions regime upon its initiation, crucially shapes the later termination process. Three key characteristics affect how, why, and with what consequences sanctions end. To begin with, the sanctioners’ policy objectives vary significantly in their degree of precision. They are laid down in the formal decision to impose sanctions – be it through an act of legislation, executive order, regulation, or via a summit communique. Ambiguous goals undermine the signal necessary to convince the target to enact a policy change (Nephew 2018). Moreover, a failure to define objectives early on can result in the development of strikingly different visions of what the sanctions’ goals are among and between the different senders, thus making decisions on sanctions relief more complicated. The Iran sanctions are a prominent example: while the EU slowly lifted its sanctions in response to the gradual advancement of the nuclear deal negotiations, the US, and in particular Republicans in Congress, viewed Iranian concessions as insufficient for sanctions relief (Politico 2015).

Similarly, the incorporation of review provisions facilitates the enforcement and ultimately also the removal of sanctions. Review provisions require policymakers to regularly oversee the enforcement of the measures, and updates them on political developments in the target state. This makes dormant or forgotten sanctions less likely. The EU arms embargo against China, officially ongoing since 1989, serves as a warning example. This embargo has practically no effect on EU arms sales to China today (Hellquist 2012: 104). Nonetheless, the measures formally remain in place, not least because this sanctions regime contains no review provisions or sunset clauses that force policymakers to evaluate its political utility on a regular basis.

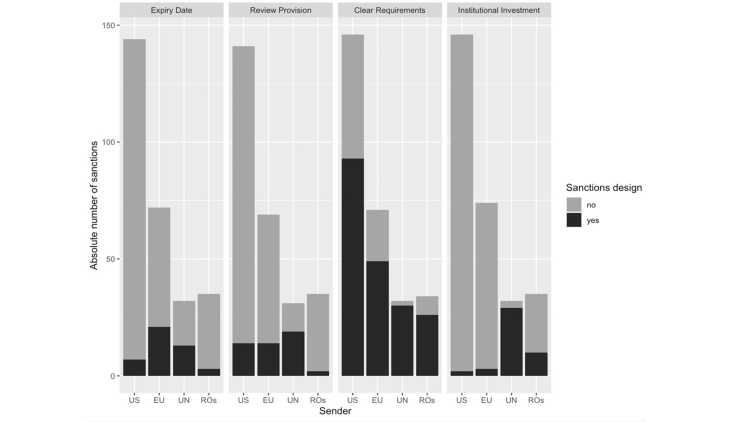

Senders differ remarkably in the design of sanctions and their oversight (see Figure 3 below). The UN is the most disciplined sender, in the sense that the majority of UN cases include both review provisions and clearly formulated requirements for sanctions relief. In contrast, US sanctions, which also have the highest average duration, only incorporate expiry dates in 5 per cent of their decisions, and review provisions in around 10 per cent of the cases. In addition, the language of the decisions is the most ambiguous compared to other senders as more than one-third of US imposition documents do not stipulate clear objectives.

Lastly, some senders invest in the institutional structure that embeds sanctions. This can affect the likelihood of termination in a threefold way. The creation of sanctions committees, task forces, or panels of experts sends a strong signal of commitment, which can increase the chances of target state compliance early on. Such structures also allow for regular evaluation of the (un)intended effects of sanctions if the case continues. However, senders can also become more reluctant to remove unsuccessful sanctions if they have heavily invested in the institutional setup. According to our data, most institutional investment is found among multilateral senders such as the UN and ROs. Bilateral senders – namely, the EU and US – rarely invest in specific committees and task forces to monitor imposed measures.

Four Lessons for Feasible Exit Strategies

With the proliferation of sanctions, their termination has also become a common phenomenon. Sanctions senders are thus confronted with the key question of how they can terminate prior restrictions in a way that proves most useful for their original objectives, or how they can avoid to lose their reputation as committed sanctioners if they lift measures despite them not having accomplished their original goals. Prior research and new data on the termination of sanctions suggests that four aspects are crucial for the arduous task of developing feasible exit strategies. First, the issue of sanctions termination must be considered from the onset. Senders should not impose measures without a road map for their eventual termination. Review provisions and sunset clauses ensure regular assessment of the measures’ political utility. Second, sanctioners should send a strong and transparent signal upon the imposition of sanctions as sanctions have higher chances to succeed at the early stages. This necessitates the articulation of clear – and ideally attainable – goals required for the eventual lifting of the imposed measures. Third, sender coordination is important for the removal of sanctions, not only for their implementation. If different actors such as the EU, UN, and US lift sanctions at notably different paces, this sends mixed signals to the regimes under sanction to which these governments can hardly react in a consistent way. Fourth and finally, timing is key. The gradual removal of sanctions can incentivise incremental change in the target state if that rolling back is tied to clear political benchmarks.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Attia, Hana, and Julia Grauvogel (2019), Sanctions Termination Dataset, available upon request.

Blinken, Antony (2015), Full Committee Hearing Iran Nuclear Negotiations: Status of Talks and the Role of Congress, www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Blinken_Testimony1.pdf (11 October 2019).

Bonetti, Shane (1994), The Persistence and Frequency of Economic Sanctions’, in: Manas Chatterji, Henk Jager, and Annemarie Rima (eds), Economics of International Security, London: Macmillan, 183–193.

Boucher, Alix, and Caty Clement (2016), Coordination of United Nations Targeted Sanctions with Other Actors and Instruments, in: Sue E. Eckert, Thomas J. Biersteker, and Marcos Tourinho (eds), Targeted Sanctions: The Impacts and Effectiveness of United Nations Action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 119–149.

Drezner, Daniel W. (2003), The Hidden Hand of Economic Coercion, in: International Organization, 57, 3, 643–659.

Early, Bryan (2015), Busted Sanctions: Explaining Why Economic Sanctions Fail, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Elliott, Kimberly Ann, and Gary Clyde Hufbauer (1999), Same Song, Same Refrain? Economic Sanctions in the 1990’s, in: The American Economic Review, 89, 2, 403–408.

Grauvogel, Julia, and Hana Attia (forthcoming), Wie enden internationale Sanktionen? Zur Bedeutung von Prozessen, Beziehungen und Signalen, in: Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen.

Hellquist, Elin (2012), Creating ‘the Self’ by Outlawing ‘the Other’? EU Foreign Policy Sanctions and the Quest for Credibility, Florence: European University Institute.

Krustev, Valentin L., and T. Clifton Morgan (2011), Ending Economic Coercion: Domestic Politics and International Bargaining, in: Conflict Management and Peace Science, 28, 4, 351–376.

Luengo-Cabrera, José, and Clara Portela (2015), EU Sanctions: Exit Strategies, Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies.

Nephew, Richard (2018), The Hard Part: The Art of Sanctions Relief, in: The Washington Quarterly, 41, 2, 63–77.

Politico (2015), Congress all but Powerless to Block Iran Deal, 8 July, www.politico.com/story/2015/07/congress-all-but-powerless-to-block-iran-deal-119821 (11 October 2019).

Schreiber, Anna P. (1973), Economic Coercion as an Instrument of Foreign Policy: U.S. Economic Measures Against Cuba and the Dominican Republic, in: World Politics, 25, 3, 387–413.

The Guardian (2016), Obama Appeals for Economic Revolution in Cuba with Call to Embrace Free Market, 22 March, www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/22/obama-cuba-embargo-free-market-economy (11 October 2019).

Wallensteen, Peter, and Carina Staibano (2015), International Sanctions: Between Words and Wars in the Global System, London: Frank Cass.

Gesamtredaktion GIGA Focus

Redaktion GIGA Focus Global

Lektorat GIGA Focus Global

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Grauvogel, Julia, und Hana Attia (2019), Einfacher zu verhängen als aufzuheben: Die langwierige Beendigung von Sanktionen, GIGA Focus Global, 5, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-65205-3

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.