- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- African States Must Localise Coronavirus Response

GIGA Focus Afrika

Afrikanische Staaten brauchen lokale Antworten auf die Corona-Krise

Nummer 3 | 2020 | ISSN: 1862-3603

Zunächst schien es so, als würden afrikanische Länder vom COVID-19-Ausbruch verschont bleiben, aber die jüngsten Entwicklungen in Afrika haben die Regierungschefs zum Handeln gezwungen. Die Berichte des African Centre for Disease Control zeigen, dass die Infektionen zunehmen. Wenn keine effektiven Maßnahmen zur Eindämmung ergriffen werden, wird dies drastische Auswirkungen auf den Kontinent haben.

Das Befolgen spezifischer Maßnahmen wie Quarantäne, soziale Distanzierung, strenge Hygieneroutinen und Reisebeschränkungen kann die Ausbreitungsgeschwindigkeit verlangsamen und den in anderen Ländern beobachteten Druck auf die Gesundheitssysteme verringern.

Die politischen, wirtschaftlichen, sozialen und infrastrukturellen Herausforderungen in vielen afrikanischen Ländern erschweren es jedoch sehr, einige dieser Maßnahmen umzusetzen. Zum Beispiel sind mangelnde Infrastruktur wie der Zugang zu Wasser und Gesundheitseinrichtungen nur einige der Herausforderungen, denen sich Afrikanerinnen und Afrikaner stellen müssen.

Zusätzlich zu den geltenden weltweiten Maßnahmen müssen die politischen Entscheidungsträgerinnen und Entscheidungsträger bereits vorhandene Strukturen berücksichtigen und nutzen sowie auf lokale Technologien und Expertise zurückgreifen.

Fazit

Neben den geltenden Richtlinien zur Eindämmung der Ausbreitung empfehlen wir, internationale Maßnahmen an die lokalen Bedingungen anzupassen. Erstens sollten lokale Akteure Menschen auf der lokalen Ebene für das Coronavirus sensibilisieren. Die Förderung lokaler Expertise und Technologien wird Implementierungskosten von Maßnahmen minimieren. Zweitens ist die Zusammenarbeit von Staat und Wirtschaft von größter Bedeutung. Regierungen sollten die lokale Produktion von persönlicher Schutzausrüstung fördern. Drittens müssen die afrikanischen Regierungschefs der Dringlichkeit der Situation gerecht werden, wenn die politischen, sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen minimiert werden sollen.

Preparing for a Potential Crisis

In just four months, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread to almost every continent. Initially, African countries seemed to have been spared the outbreak, but recent infections across the continent have nudged leaders into action. In response, African countries have instituted measures including the standard quarantining of infected or suspected patients, travel restrictions and border closures, physical distancing, and curfews. These measures are consistent with those recommended by the World Health Organization, the various Centres for Disease Control (CDCs), and those followed by many countries dealing with the virus too.

As of now, a combination of these measures appears to be the most sensible way to prevent infection, slow the speed of it, and reduce the pressure on healthcare systems. With Africa’s relatively low infection rates at the moment, the best shot countries have at countering the virus’s spread is to prioritise the containment and prevention of community infections. However, political, economic, social, and infrastructural challenges in many African countries make it difficult and indeed impracticable to implement some of the measures like quarantining, intensive care, and physical distancing currently being adopted in other continents.

As a result, African countries need to evaluate the structures in place and adapt global measures to local conditions. In addition to such measures, policymakers must utilise local structures and draw on local technologies and expertise to control the spread of the virus. Localisation is not antithetical to the use of measures implemented elsewhere. Rather, it means African countries using local measures in tandem with adapting external strategies to local conditions where necessary.

COVID-19 Measures Meet Africa

Although the idea of “physical distancing” has become a most prominent strategy in the current context, the strategy is not new as a means of containing pandemics. In the past, public gatherings have been cancelled as a way to contain the spread of disease. Therefore, it is not surprising to see the measure applied again to contain the spread of COVID-19. As relatively easy to apply as physical distancing, curfews, and shutdown may be in European countries however, in the African context implementing such measures is by no means straightforward. Many African governments have begun to institute curfews, shutdowns, and travel bans but they still have to deal with the difficulty of implementing physical distancing and to handling the other factors that come along with it.

Many African cities, towns, and villages are way more crowded than their European counterparts when compared in terms of their landmass. The population density for Luanda is about 25,000 residents per square kilometre, while Lagos is estimated at 6,000 residents per square kilometre. The spread of the virus in such cities will have more drastic consequences, and it will be a far greater challenge for governments to halt or manage the movement of people in these areas. In most towns and rural communities, physical distancing might be tricky when local markets remain open given that they are essential. This is because these local markets are crowded and have open stalls; managing or mitigating the influx of people will be a daunting task. In poor and densely populated cities and towns, this could cause the spread of the virus to escalate.

In addition to the movement of people, there is the question of the culture of communality which has survived all historic periods. Communality is so much at the core of African culture that it has managed to remain part of social life even after colonisation and into the age of globalisation. Hence, it is not uncommon to have not just immediate but also extended family members living together under one roof. Therefore, in some cases, villages and communities may not be densely populated but the living situations are in bad conditions in poor households. If the government manages to control movement, there is still the challenge of ensuring that precautions are followed in households of more than ten people. There are also villages and communities with low population densities that are relatively difficult to access. For example, Idjwi Island in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Samburu County in Kenya, and the village of Odeni-gida in Nasarawa State, Nigeria, are just a few of the many remote places of the continent that have little to no information on the pandemic. In such places, agricultural production is the main source of income, and every member of the community is in one way or another involved in the transportation of commodities. Hence, their remoteness does not inhibit the spread of disease. If today’s health challenges are approached in such a way as to cater for tomorrow and beyond, then these communities must be sensitised to the pandemic and the precautionary measures to be taken.

Given that many villages in Africa are remote, this also means that in most cases basic infrastructure is not available for the masses. For instance, in Odeni-gida, communities have no electricity, no telecommunication providers, and have limited access to clean water. Dealing with the issue of access to water is of the utmost importance to prevent the spread of the virus: the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) records that one-third of all African countries suffer from a scarcity of clean water (ECA 2006). These issues pose a challenge to access to proper hygiene routines. The Africa CDC is concerned that a spike in the number of cases will totally overwhelm respective healthcare systems. For instance, Kenya, a country of more than 50 million people, has only 130 intensive care units and only 200 intensive care nurses (Nordling 2020); Odeni-gida, only one clinic and two beds. Initially, only Senegal and South Africa had equipped facilities to test for the virus; without these, the continent was at risk of lacking the means to monitor and contain the spread of COVID-19, the outcome would be a situation of under-reported or not-reported cases of the virus. To contain the spread, countries need to know the number of infected people. If there are not enough facilities, the accuracy of confirmed cases and who to quarantine or treat becomes close to impossible. If preventive measures are not taken seriously, Africa might be sitting on a powder keg.

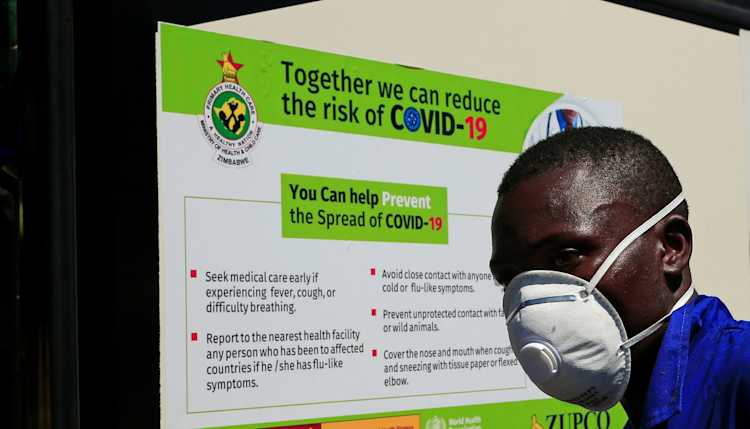

At the moment, the most pressing problem that African countries face to effectively kick-start the implementation of measures is sensitisation. Amidst measures already put in place by African governments like the closing of borders in Uganda, suspension of all international passenger flights to and from Kenya, the shutdown in South Africa, and the closing of intrastate borders in Nigeria, misinformation could lead to the ineffectiveness of implemented measures. There are two extremes to the challenge of misinformation currently affecting responses. On the one hand, many African people are going about their daily lives without adhering to precautions. There are church services, prayers in mosques, weddings, and parties. This is because there is an unfounded popular assumption that black people cannot contract COVID-19. Although this notion seemed quite prevalent in African-American communities in the United States, it is also the case that it holds strong currency in Africa too. Several social media messages are circulating that the virus does not affect Africans; others say it is an invention of Europeans to kill Africans.

Religion also plays a huge role in the nonchalance of people towards taking precautions. A good instance is a comment by the Tanzanian president, John Magufuli. In his speech to a church congregation, the president likened the pandemic to Satan, needing divine intervention to be quelled. He further stated that churches and mosques will remain open because that is where “there is true salvation” (Ng’wanakilala 2020). Islam and Christianity have a stronghold in Africa, and heavily influence the way people think. So much so that, in most cases, religious leaders have more legitimacy than political ones. Even with the government ban, a Nigerian pastor held an evangelical gathering with 30,000 people. This tendency to obey religious leaders more explains the indifference towards COVID-19 measures and poses a threat to their implementation. On the other hand, misinformation leads to stigmatisation and discrimination. If people are not accurately informed, they might regard infected individuals as dangers to society. In extreme cases, this could lead to physical violence – as seen in the case of Kenya (Fredrick 2020).

If the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread as drastically as it has in other world regions, it will affect African social life as we know it. Given that social welfare is almost non-existent in most African countries, vulnerable groups could be hugely affected by the outbreak. It is uncommon in African societies to have retirement homes because taking care of the elderly is the responsibility of family members. Therefore, in times of physical distancing and intrastate travels bans, catering to the elderly may become more difficult. This also applies to the homeless. Usually, these groups do not receive any social benefits from the government; they mostly rely on alms handed to them on the street or through charity organisations. A shutdown would mean that some vulnerable groups will be left to fend for themselves.

Political and Economic Implications

Disasters like the outbreak of disease are political and economic problems, as they affect decisions of government in these sectors. Regardless of how the CODVID-19 outbreak unfolds in Africa, its countries are bound to suffer political and economic repercussions. As they direct resources to the COVID-19 response, leaders have cut down on routine government business – especially that requiring in-person contact. Some legislatures continue sitting but mainly to consider emergency bills, while others like in The Gambia and South Africa have suspended sittings indefinitely. With two South African and a few Nigerian politicians testing positive for the virus after meeting with foreign delegates who later tested positive themselves, further precautions may lead governments across the continent to operate at reduced capacity.

While some measures can be easily reversed when the outbreak subsides, an epidemic can force political choices with more fundamental repercussions. Opposition parties may not enthusiastically cooperate with authorities out of worry that incumbents may gain political capital from steering the crises; in their bid to control disasters, incumbents can overstep their authority or usurp emergency powers for their political benefit. In this case, the initial crisis can evolve into a worse disaster. With parliamentary and presidential elections due this year in 22 African countries, an epidemic – or even protracted slow infections – will perpetuate a state of uncertainly that is bound to disrupt electoral calendars in the form of delays, postponements, and cancellations. However, many of the choices made on elections will, to an extent, depend on each country’s infection rate and the risk-analysis that institutions conduct. For instance, after conducting such analyses, Mali with 15 infections as of late March went ahead to hold its long-overdue parliamentary elections, while Ethiopia, which had confirmed 25 cases, postponed elections initially scheduled for August.

One fear is that justifiable containment measures like physical distancing and shutdown, which disperse group activities and disempower organisations, may just prove to be the right conditions for overzealous government agents to perpetuate corruption and commit human rights abuses. For instance, countries like Sierra Leone and Togo have declared a state of emergency over COVID-19. Whether Rwanda’s total shutdown or Sierra Leone’s 12-month “State of Emergency” are attempts at overreach by incumbents to monopolise the political scene or just proportionate responses from Ebola-traumatised countries are too early to tell. The verdict will lie in how such measures help to protect the population, and how safely leaders steer the countries back to normalcy afterwards.

A protracted pandemic will be even more devastating for African economies. Until a few weeks ago, they were among some of the fastest-growing in the world – but the outbreak will now push many into recession. Like other disease outbreaks, COVID-19 is shaping demand-and-supply forces, fiscal policy, and economic regulation. As with previous global crises, Africa’s small industrial sector makes its countries somewhat insulated from industrial shrinkage (ADB 2009). But since countries heavily depend on foreign production for essential and non-essential imports, COVID-19’s economic impact on the continent depends not just on what African leaders do but also on external dynamics. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), uncertainty over the COVID-19 trajectory in Africa is already stifling foreign investment (UNCTAD 2020), while UNECA estimates that falling demand from China will make Africa’s oil-producing countries lose about USD 65 billion in revenue. The entire continent may, further, lose about 50 per cent of its gross domestic product as commodity prices and demand fall (ECA 2020). If trade partners shift significant domestic manufacturing from export into emergency COVID-19 responses internally, Africa will not only be denied the critical machinery needed for industrialisation but also become a secondary priority regarding COVID-19 supplies – which will become expensive. Tourism and remittances, two of Africa’s highest revenue earners, are also taking a hit. Though the continent is set to lose only a small percentage of the estimated 50 million jobs under threat in the global tourism sector (WEF 2020), this still spells dire prospects for African employees and their families.

Sectors that will have their budgets cut or redirected to the virus response will miss their growth and impact targets. Africa’s economies are about 60–90 per cent informal (ADB 2019) and employ the majority of the continent’s vulnerable – who survive solely on the daily profit they make. However, the partial shutdown across the continent is gradually eroding such daily income and will further jeopardise even the most ordinary of lives. With such dangers to corporate and consumer economic well-being, governments face fiscal deficits and will have to look elsewhere for support. While loans and grants may provide temporary relief, they will not curtail a recession – circumstances which will only perpetuate the continent’s debt problem.

Implications for Regional Integration

COVID-19 comes at a time when African countries are working to accelerate regional economic integration with policies like the common currency in West Africa, the Eco, and the Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) set to commence in July. As they shift attention and resources to the domestic fight against the virus, leaders may delay or even abandon these sub-regional and continental projects. Delay and abandonment would be consistent with the observation that African countries tend to disengage from regional processes when they have competing domestic priorities, or when they feel that integration projects are encroaching on their sovereignty.

In crisis periods, Africa’s regional organisations are often powerless. This is because they are not supranational and therefore can neither coerce member states into adopting certain measures nor forcefully ensure compliance with existing policy. Rather, the African Union (AU) and its sub-regional organisations are relevant to the extent that they generate goodwill from and build consensus among member states, facilitate resource mobilisation, and lead the creation of new institutions. The Africa CDC is providing technical leadership and health expertise in the various sub-regions, while the Economic Community of West African States is facilitating the creation of a West African laboratory complex and Centres for Disease Surveillance and Control to fight COVID-19 and other disease outbreaks. Additionally, the AU Commission has secured a promise from Cuba to help African countries combat COVID-19 if need be.

However these initial responses are limited, not only because the organisations depend on the willingness of member states to comply but also because without a vaccine or clinically proven treatment COVID-19 is currently contained by partially collapsing the structures meant to fight it. For instance, Africa’s regional organisations and their projects thrive on extensive travel and conferences within and outside of the continent, but the outbreak has forced institutions like the African Development Bank (AfDB), the African Court on Human and People’s Rights, and the AU into weeks of physical distancing and remote work. It follows that until a proven treatment is found, or African countries record months of zero infections and institutionalise the mandatory testing of all foreign arrivals and periodic testing for office staff, the implementation of major projects on African integration like the AU’s Agenda 2063, the common African passport, the Eco, and the AfCFTA will, at best, be delayed.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that what Africa needs at the national, sub-regional, and continental levels is decisive leadership in the fight against COVID-19 – especially as experiences elsewhere show that grim consequences await countries that hesitate to act with conviction. The ramification of this is that the implementation of development plans will take a back seat as resources shift to the COVID-19 response.

Africa must Localise Its Response

Given that African countries currently seem to have relatively low infection rates, the most politically, socially, and economically practical strategy is to stay ahead of the virus by implementing containment measures. If effectively implemented, such measures will stop the virus from spreading further. Policymakers need one foundational component herein: an emergency mindset. Some have even argued that Africa’s problems are so dire that leaders must approach even “normal” policy issues as unprecedented emergencies requiring urgent action (Nyoni 2019). The virus has not created new economic and political challenges for Africa; it has merely exacerbated long-standing ones. Therefore, emergency responses in these countries should be considered only the first phase in a much-needed, urgent, long-term strategy. Since African countries cannot afford extended periods of shutdown, the aim of governments – besides the self-evident purpose of containment – should be to restore economic life as quickly as possible.

African countries must localise their response to COVID-19 in a way that addresses the peculiar political, economic, and social structures. By localisation, we mean that, to the extent possible, policymakers must put African leadership, expertise, and technology at the centre of their response programmes. Localisation is not antithetical to global guidelines; learning from the experiences of others is not either. However, successful response requires African countries taking charge of their fate even as part of global processes. This argument for a localised response is based on the observation that as all countries, including the so-called donors and development partners are preoccupied with their national responses, no one can take on Africa’s burdens. Besides, experts believe COVID-19 may return in the near future, suggesting that leaders must think and act beyond the current outbreak. Policymakers do not need to invent every measure from scratch. They have already adopted some of these, but because Africa’s challenges are so fundamental, the responses need to be intensified and maintained over the long-term as part of regular developmental policy.

More people should be trained to monitor and test for the virus. This should include medical professionals and volunteers. The countries that were affected by Ebola appear to be ahead of this. Liberia, Senegal, and Sierra Leone have trained community workers to proactively check for symptoms and share health information in places where people lack access to the Internet or government services (Peyton 2020). Nigeria has set up and trained rapid response teams in all 36 states of the country (Ihekweazu 2020). Such responses need to be replicated in other parts of the continent to halt the further spread of the virus.

Testing and treatment should be accompanied by intensive public education through mass-media campaigns. In remote communities lacking access to these forms of information, agents should be deployed to keep the masses informed. Traditional African rulers and religious leaders tend to have high levels of legitimacy among the people and should provide leadership in this crisis period. In Ghana, for instance, the ruler of the Asante Kingdom has attached a humanitarian supplies programme to the intensive public-education initiatives run by his office. In communities where town-criers are still employed, they can act as agents of communication as well. They could serve as volunteers to sensitise and to also inform people about who to reach out to if they feel they are experiencing symptoms. Vans could be turned into makeshift clinics for testing in remote communities. The challenge of clean water and running taps in homes have to be addressed. For example, governments could ensure that tanks deliver clean water to remote areas.

African countries must also invest in the search for preventive technologies, vaccines, and treatment. Senegal’s Pasteur Institute is at an advanced stage of developing a rapid test kit for the virus, a development which if successful will lead to timely diagnosis and early intervention as part of containment measures. Some universities in Ghana and Liberia have for the first time released unto the market hand sanitisers, a key component of the COVID-19 prevention regime. Not only do these measures make expertise available in the current crisis, but they also lay good foundations for African countries to integrate home-grown research into long-term development strategy. Furthermore, the use of Veronica Bucket in Ghana has presented an alternative for homes without running taps. Such low-cost technologies should be replicated in other African countries.

Simultaneously, the government must introduce social protection for the vulnerable. An emergency food and nutrition programme should be initiated especially for the disabled, unemployed, rough sleepers, and those recently retrenched in cities that have been shut down. As earners of irregular income in the informal economy, these people will suffer most from the increasing shutdown of daily economic activities. Again, this should be eventually linked to a more formalised social protection system.

For corporate organisations, governments should introduce an economic stimulus package of some sort. A few countries like Botswana, Ghana, and South Africa have already dedicated funds to help cushion economic effects for companies in selected sectors. But since many African countries cannot provide a direct corporate financial boost, policymakers must consider commissioning capable local manufacturers for the emergency production of personal-protection equipment and sanitation products. For instance, a coalition of private companies led by Nigerian billionaire Aliko Dangote is currently mobilising to manufacture products and donate funds not just to Nigeria but other African countries to help fight the virus (Onu 2020). Within the continent, countries can secure financial support from the AU COVID-19 Response Fund, and the USD 3 billion Fight COVID-19 Social Bond introduced by the AfDB. They can seek additional support from the USD 50 billion emergency rapid-funding scheme of the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility. Ghana, for instance, has obtained nearly USD 100 million from the latter to fight COVID-19. Other external partners like China, the European Union, and the US can be of help by aligning their projects to the localisation agenda. However, countries must acknowledge the implications of accessing these facilities for their subsequent fiscal policy. They could, then, cushion themselves by negotiating with donors for debt forgiveness.

At the sub-regional and continental levels, African countries and their institutions should cooperate to deliver more social, economic, and political normalcy in times of crisis. As the AU provides moral leadership and mobilises African experts to fight COVID-19 as it did during the Ebola pandemic, the current outbreak is an opportunity for the Africa CDC and its sub-regional offices to negotiate for an expanded mandate that empowers them to enforce compliance with uniform regional health standards and procedures. In the medium- to long term, the West African countries that will soon launch the Eco must also consider a common fiscal policy that will help share the risk and reduce the shocks of the recession that is almost certain to hit their economies. As regional and continental bureaucrats continue to physically distance themselves, implementation of projects like the AfCFTA, common passport, and Agenda 2063 are likely to be delayed. Authorities should conduct scenario analyses regarding COVID-19-induced delays and use the results to optimise the implementation of countermeasures. Work on the AfCFTA should especially be expedited, so that African companies can enter the economies of member countries and thereby increase job opportunities for those facing recession.

Lessons to be Learned

Usually, the continued relevance of an emergency policy depends on the trajectory of the problem that created it in the first place. However, in the case of many African countries, the challenges currently faced are so fundamental that even if COVID-19 ends today, many will still have to contend with the problems of inadequate health infrastructure, stunted economic growth, limited social protection for the vulnerable, a small manufacturing sector, and in some cases the abuse of political and human rights. What COVID-19 has done is to push African countries to address these long-standing issues with a greater sense of urgency. Unlike in some Asian and European countries, the virus’s delayed entry into Africa gave policymakers a head start on mitigation measures. The more likely story is that with aggressive testing, intervention, and the combination of proposals that have been put forward here, African countries can avert the catastrophe of community infection and mass fatalities. However with expert predictions that this or other viruses will return in the near future, Africa’s safety will depend on the ability of its leaders to maintain an emergency mindset over the long term and thus address challenges with urgency.

Aside from containment, the main job political leaders have is to protect citizen’s rights and steer their countries back to normalcy. Even in fast-paced decision-making under situations of emergency, governments must demonstrate the will to make political decisions that are as consultative and transparent as possible. They must act within constitutional powers, and not interfere with the legislature, the judiciary, and media. To the extent that their mandates permit, sub-regional organisations and the AU must conduct scenario analyses for on-time and delayed elections and institute the necessary mitigation measures.

Fußnoten

References

ADB (African Development Bank) (2009), Africa in the Wake of the Global Financial Crisis: Challenges Ahead and the Role of the Bank, Abidjan: African Development Bank.

ADB (African Development Bank) (2019), Jobs, Growth and Firm Dynamism, Abidjan: African Development Bank.

ECA (Economic Commission for Africa) (2020), ECA Estimates Billions Worth of Losses in Africa Due to COVID-19 Impact, Addis Ababa: Economic Commission for Africa.

ECA (Economic Commission for Africa) (2006), Management Options to Enhance Survival and Growt, https://docplayer.net/16703032-Economic-commission- for-africa-management-options-to-enhance-survival-and-growth.html (26 March 2020).

Fredrick, Fadhili (2020), Kwale Youths Attack, Kill Man over Coronavirus, in: Daily Nation, www.nation.co.ke/counties/kwale/Kwale-man-accused-having-coronavirus-attacked--dies/3444918-5495558-c3a17n/index.html (27 March 2020).

Ihekweazu, Chikwe (2020), Steps Nigeria is Taking to Prepare for Cases of Coronavirus, in: The Conversation, http://theconversation.com/steps-nigeria-is-tak ing-to-prepare-for-cases-of-coronavirus-130704 (30 March 2020).

Ng’wanakilala, Fumbuka (2020), Tanzanian President Under Fire for Worship Meetings Amid Virus, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-22/tanzanian-president-under-fire-for-worship-meetings-amid-virus (27 March 2020).

Nordling, Linda (2020), ‘A Ticking Time Bomb’: Scientists Worry About Coronavirus Spread in Africa, www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/ticking-time-bomb-scientists-worry-about-coronavirus-spread-africa (27 March 2020).

Nyoni, Jabulani (2019), Decolonising the Higher Education Curriculum: An Analysis of African Intellectual Readiness to Break the Chains of a Colonial Caged Mentality, in: Transformation in Higher Education, 4, https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v4i0.6.

Onu, Emele (2020), Africa’s Richest Man Helps Lead Nigeria Charge Against COVID-19, www.bnnbloomberg.ca/africa-s-richest-man-helps-lead-nigeria-charge-against-covid-19-1.1412671 (1 April 2020).

Peyton, Nellie (2020), Using Lessons from Ebola, West Africa Prepares Remote Villages for Coronavirus, www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-africa- ebola-idUSKBN21C38B (30 March 2020).

UNCTAD (2020), Impact of the Corona Virus Outbreak on Global FDI, Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

WEF (World Economic Forum) (2020), This is How Coronavirus Could Affect the Travel and Tourism Industry, Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

World Population Review (2020), World City Populations 2020, https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/ (26 March 2020).

Gesamtredaktion GIGA Focus

Redaktion GIGA Focus Afrika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Afrika

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Iroulo, Lynda, und Oheneba Boateng (2020), Afrikanische Staaten brauchen lokale Antworten auf die Corona-Krise, GIGA Focus Afrika, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-67242-7

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.