- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Not a Storm in a Teacup: The Islamic State after the Caliphate

GIGA Focus Middle East

Not a Storm in a Teacup: The Islamic State after the Caliphate

Number 3 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Despite the loss of its territorial “caliphate” in 2019, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (IS) still poses a daily threat to the societies of the region and beyond. To account for the resurgence of IS, we need to look at its dynamism, in addition to the domestic and regional complexities that facilitate its persistence in Iraq and Syria.

The gradual, drastic loss of territorial control in Iraq and Syria since 2015 has deprived IS of crucial assets to launch large-scale terrorist attacks and compelled it to change its tactics.

Since 2019, IS has intensified its guerilla warfare and, by destabilising large parts of Syria and Iraq, managed to maintain leverage in those areas.

The organisational and ideological cohesion of IS has not deteriorated significantly, even after losing its territorial base and its “caliph,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

IS exploits the political, security, social, and economic fragmentations that continue to plague both Iraq and Syria and that contributed to its rise in the first place.

Refugee camps and detention centres, especially in northeast Syria, are currently being targeted by IS for infiltration and radicalisation. If these campaigns are successful, IS may be able to regain thousands of fighters.

Policy Implications

The EU should increase its support vis-à-vis the refugee camps in Syria and Iraq by providing humanitarian aid and adopting an institutionalised policy for repatriating its citizens who have joined IS, along with their families. This should be complemented by measures of prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration. If not addressed efficiently, today’s legal conundrums and poor humanitarian conditions of European citizen detainees could become tomorrow’s security challenges.

The End of the Islamic State’s Caliphate

In 2017 the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (IS) lost control over its former capital, Mosul. Two years later, in 2019, IS was defeated in the Syrian town of Baghouz. These two events marked the end of the “caliphate” as a territorial, quasi-state project that, at its height, had conquered swaths of land in Iraq and Syria almost equal in size to the territory of the United Kingdom. Despite its loss of territory, IS has not been terminated. Instead, various signals in 2020 and early 2021 suggest IS’s continued local resilience and tentative resurgence.

However, the emergence and resurgence of IS cannot be seen as isolated from the multifaceted obstacles that Iraq and Syria face. The persistence of IS is due both to its own characteristics and to the contextual conditions in these two Middle Eastern countries. In this vein, it is still unclear precisely how and when IS can be terminated in the long term. What is clear, however, is that some additional action can be taken in the short run to foreclose IS’s attempts to radicalise and recruit civilian populations – especially in refugee camps in Iraq and Syria – by, for instance, intensifying humanitarian support as well as repatriating foreign fighters and their families.

The Islamic State’s Caliphate as a Proto-State

An offshoot of al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI), IS first emerged in Iraq in 2006 under the name the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI). Later, it faded into obscurity mainly due to the heavy presence of US troops in Iraq. In 2011 IS re-emerged and expanded its operations into Syria under the leadership of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Raqqa (Syria) and Mosul (Iraq) fell into the hands of IS in 2014, and the “caliphate” of the Islamic State was subsequently declared (The Wilson Center 2019). Relatedly, an examination of IS’s targets has revealed that the organisation attacks both state security forces and civilians. This blurs the analytical classification of IS as being either a guerrilla movement or a terrorist organisation. In reality, IS embodies the characteristics of both terrorist and guerrilla groups.

At its height, IS controlled a territory that stretched from Aleppo, in northwestern Syria, to Diyala, in northeastern Iraq. This, in turn, enabled the terrorist organisation to enlarge its resources of funds and manpower through human trafficking (especially of children and women); collection of zakat (Islamic alms) from farmers; amassing revenues from oil, gas, and phosphate fields and refineries; trading in agricultural products; smuggling archaeological artefacts; kidnapping for ransom; holding cash currency from banks and taxing bank transactions; and accumulating illicit taxes from transit areas. Through the control of income resources, logistical routes, and a delineated territory, IS was able to exert proto-state functions such as levying taxes; applying Sharia law and an Islamic judicial system; designing and imposing an “Islamic” curriculum for schools; and providing basic services such as electricity (FATF 2015: 12–24).

Ideological activism, too, was on the IS agenda, as it relied on different media to convey various messages in pursuit of three main objectives: to disseminate its ideology, to recruit new members, and to raise funds for its operations. IS drew on the modern networks of communication technology to establish an array of outlets, such as al-Hayat Media Center, the magazine Dabiq, and Amaq News Agency. Also, it was present and active on social media applications such as Telegram, and used the internet to post videos of hostages being beheaded. In terms of the content of IS propaganda, the organisation called for a “holy war” (jihad); used language that referred to the “caliphate”; and invoked verses from the Qur’an, Hadith, and Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). A further alarming aspect of IS discourse was its view of the Shiites as rejectors (rawafidh) and of other minority groups, such as the Christians and Yazidis, as heretics.

In response to the regional and global menace that IS represented, in 2014 the United States began an international campaign to counter the dispersion of this proto-state. This initiative came to be known as the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS and was supplemented by the establishment of the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR), which entailed a partnership of 64 countries – some from the Gulf region (including the United Arab Emirates and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) and from the EU (including Germany, France, and Italy) – whose principal mission was to defeat IS. In Iraq, Operation Inherent Resolve coordinates with the Iraqi Army, the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), and the armed forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) – the Peshmerga. In Syria, the United States’ primary partner is the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which operates in the northeast. The US-led military campaign and its partners on the ground managed to take back the territory of the Islamic State in 2019 through coordinated military airstrikes, surveillance, reconnaissance, and field battles. On the request of the Iraqi government, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) established a new non-combat mission in Iraq in 2018 that was designed to build the capacity of the Iraqi Army and ISF via education, training, mentoring, and advisory activities to prevent the resurgence of IS. In 2020 NATO defence ministers came to an agreement with the Iraqi government to further extend the mission.

A Deadly Insurgency on the Rise

Having lost control of territory, many IS fighters fled to unpopulated, deserted villages and/or loosely governed areas, whereas others dissipated into civilian communities seeking safe havens. Further, the group turned to guerilla insurgency tactics of forming small fighting units that use surprise attacks, targeted assassinations, and improvised explosive devices (IED). One of IS’s imperatives today is to retain leverage in border areas between Syria and Iraq and between Iraq and Iran to secure free movement of its fighters and collect illicit taxes from the trade and oil routes. A second current imperative is to stymie the return of stabilisation and normalisation to liberated areas (Al-Hashimi 2020).

The organisational and operational capacities of IS have survived degeneration and collapse. The killing of IS “caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2019 was followed by a seemingly undisputed leadership transition to the new and still less known “caliph,” Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. On the level of operations, decision making has been further devolved to the discretion of unit commanders in the field. Likewise, the theatres of IS activities have been divided into province-based sectors (wilaya), whereby Iraq, for example, is divided into 11 IS operations sectors. As a result, even though IS lost its last territorial redoubt and its first “caliph” in 2019, it weathered these existential threats and managed to preserve its internal cohesion without fracturing or splintering (Hassan 2020).

The scale of IS attacks in Iraq and Syria in 2020 and early 2021 may attest to the resurgence of the group. For instance, between July and September 2020, IS conducted 228 attacks in Iraq and 131 in Syria (U.S. Department of Defense 2020: 19–23). Most of these attacks took place in the two border provinces of Diyala (Iraqi–Iranian border) and Deir ez-Zor (Syrian–Iraqi border), which hints at the noticeable presence of IS across border areas. In the same vein, IS seems to be escalating its operations in 2021: In January, 153 members of the Syrian regime forces and their supporting militias were killed by IS in various areas stretching from Aleppo, Hama, Raqqa, and Deir ez-Zor to the Homs desert (part of the Badia) (al-Kanj 2021). Similarly, IS advanced its presence from the outskirts of Iraqi cities to hit central Baghdad on 21 January with two suicide bombings that left 32 people dead and more than 100 wounded.

Currently, the most intractable among the activities of IS might be its financial schemes. In 2015, when the “caliphate” was at its zenith, IS earnings and holdings reached an estimated USD 6 billion (Warrick 2018). The fall of the territorial reign of IS had deprived it of valuable resources that came with conquering territory, such as direct revenues from trading in natural resources and taxes from the populations under its control. However, IS today is not financially burdened by the need to secure and maintain the territorial holdings that it once seized. Also, the obligation to equip and pay salaries to large numbers of fighters or to fund large-scale armed operation has diminished significantly. This may leave IS with more latitude to focus on eclectic violence and pick its targeted attacks more rationally.

As former IS commanders reveal, in 2017 when IS was ousted from Raqqa, the organisation transported millions of dollars from Raqqa to the city of Baghouz, to which IS leaders and fighters headed and resided until 2019 (Al-Ghadhawi 2020). Money laundering also represents a major asset for IS today, as it invests its cash holdings in “legitimate” commercial and business enterprises such as hotels, real estate, and car dealerships across Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and the United Arab Emirates (Kenner 2019). Further, to evade traceable banking transactions, IS draws on a complex web of money services businesses (MSB), hawala systems, and financial facilitators to move its illicit funds. For years, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) at the US Department of the Treasury has been tracking and designating networks, entities, and individuals who collaborate in funding or facilitating the financial operations of IS. Between 2018 and 2019, for example, the OFAC designated the Iraqi-based MSB Afaq Dubai and the network coordinated by financier Fawaz Muhammad Jubair al-Rawi as circumventing the banking system via reliance on hawalas to move money for IS across the Middle East, Africa, and Europe (U.S. Department of the Treasury 2019).

Fragmentations in Iraq and Syria are Conducive to IS’s Resurgence

IS has adapted to the loss of its territorial “caliphate” by adjusting its warring tactics and financial practices, consolidating the cohesion of its organisational and ideological constructs, and bolstering its operational resilience. However, it is misleading to isolate IS from the broader developments in Syria and Iraq and to assume that IS’s resurgence can be ascribed merely to its adroit adaptability.

In Iraq, the drop in oil prices added to the economic and political malfunctions of the government and contributed to the outbreak of mass protests in October 2019. COVID-19 compounded the situation, further straining the performance of the government. Also, the successive governments of Iraq have been characterised by the endemic blurring of the boundaries between state security institutions and the myriad Iran-backed Shiite militias. Similarly, disputes between the government in Baghdad and the KRG over issues of influence and governance in provinces such as Kirkuk created security gaps that enabled IS to increase its attacks there.

On a different level, we do not yet know how US–Iranian relations under the new US administration of Joseph Biden will affect Iraq. However, the partial US military withdrawal from Iraq following the directives of former president Donald Trump had already emboldened the Shiite militias in Iraq against the US and had also given IS more latitude to stage new attacks at the expense of the Iraqi state. Another international engagement with Iraq whose progress should be re-evaluated is that of NATO and, within its framework, the German military. As mentioned before, in 2020 NATO decided to extend its non-combatant mission in Iraq. Likewise, the German Bundestag agreed in October 2020 to prolong the German military presence in Iraq until January 2022 within the frameworks of the NATO mission and the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. The call to re-evaluate the achievements of the German and NATO efforts is primarily based on two facts: First, when the October protests kicked off, mainly in central and southern Iraq, the ISF (along with some militias) used excessive force and live ammunition to quell the mass movement, resulting in the killing of more than 500 protesters (Alsaafin 2020). Second, the twin suicide attacks in central Baghdad in early 2021 attest to the fragile security situation and the dearth of stability even after years of international programmes designed to stabilise the country.

In Syria, too, IS has ample fragmentations to avail itself of. The country is divided into discrete zones of military, economic, and political control. The areas where IS is most robust lie in the northeast, where the US-backed SDF holds control. However, tensions between the SDF and Turkey have led the latter to undertake three incursions into northern Syria (in 2016, 2018, and 2019) to protect what Ankara claims is its national security. Additionally, the complexity of the security landscape has created ungoverned spaces, such as the Homs desert, which has seen an increase in IS attacks. The longevity of the war in Syria and the stalled peace process in compliance with UN Resolution 2254 only add to the challenge that IS poses for local communities in terms of intimidation, displacement, and recruitment.

In short, the destruction of IS entails addressing the initial factors that enabled it to emerge in the first place. Those factors exceed IS-related aspects of resilience and touch upon the structural obstacles of Syria and Iraq that allow IS to thrive.

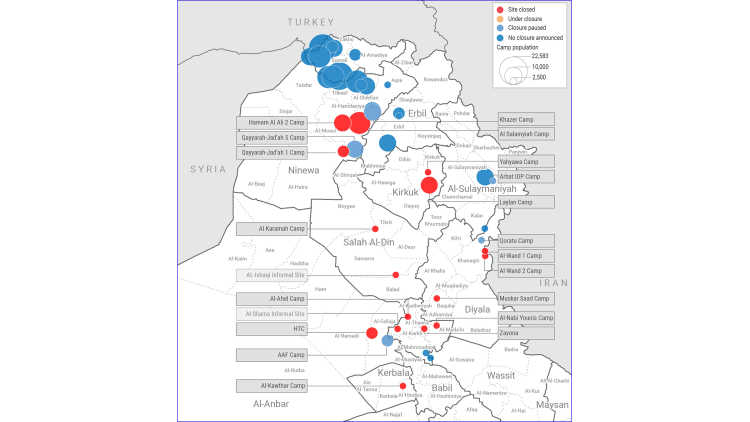

IS and the Refugee Camps in Syria and Iraq

IS terrorism and the fight against it have rendered hundreds of thousands of persons in Syria and Iraq homeless and displaced. In turn, various refugee camps and detention centres have been established in the two countries. As of December 2020, Iraq had more than 1,220,000 internally displaced persons (IDP) and hosted approximately 330,000 refugees. Of the refugees, more than 240,000 are Syrians, 40,000 are of other nationalities, and 47,000 are stateless. Whereas 60 per cent of the refugees in Iraq reside in urban areas, most of the rest are dispersed in refugee camps in the northern Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI).

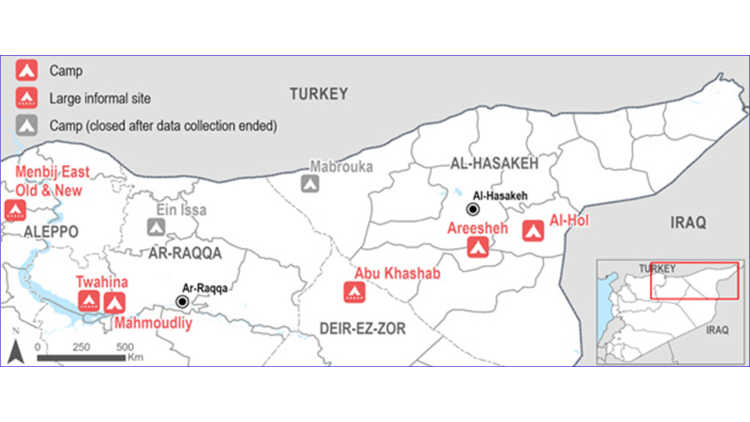

In Syria, thousands of families and individuals have been displaced and hosted in camps, tents, farms, schools, and buildings in the country’s northwest, south, and northeast. However, IS fighters and their families were generally displaced in the northeast between the governorates of Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Hasaka. Relatedly, al-Hawl camp in northeastern Syria has received broad attention from the UN, state governments, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) due to its hosting of more than 64,000 refugees and IDPs, of whom 80 per cent are women and children. Al-Hawl and Roj refugee camps in northeast Syria are detaining 31,000 foreign children under terrible humanitarian and security conditions, without proper healthcare or education (Middle East Monitor 2021).

A report submitted to the UN Security Council in February 2021 (U.N. Security Council 2021: 18–20) describes instances of radicalisation, minors’ indoctrination, and training at al-Hawl camp. Furthermore, funds have been reported to be pouring into and flowing out of al-Hawl camp to support the families of IS members and finance their escapes from the camp. Those funds mostly take the form of remittances sent to recipients in neighbouring countries through registered banking sectors, to then be transferred to the camp through hawala companies and MSB.

The UN report estimates the number of male IS fighters who are detained in northeastern Syria to be approximately 11,000, of which 2,000 are foreign terrorist fighters (FTF) from 60 nationalities; 1,600 are Iraqi nationals; 5,000 are Syrian nationals; and 2,500 are of unknown nationality. COVID-19 has aggravated the poor humanitarian conditions at the detention facilities. It has also challenged the capacity of the Kurdish de facto authorities who manage and secure the camps and detention centres in northern Syria, causing a drop in the number of guards from 1,500 in 2019 to 400 by late 2020.

In 2021 violence in al-Hawl camp, including the murder rate, has continued to rise. This drove the SDF and its internal security force (Asayish) to launch a security campaign between 28 March and 2 April against alleged IS sleeper cells in the camp. As a result, 125 suspected IS members were arrested, and military supplies and electronic circuits that can be used in explosive devices were found.

The brittle security landscape in Syria and Iraq, in addition to the humanitarian and economic burdens imposed by COVID-19 on state and non-state actors alike, may prompt IS to plan for intensive jailbreaks in 2021. If such a scenario materialises, IS will welcome thousands of its battle-hardened operatives back into its ranks, reversing the effects of years of fighting and magnifying its threat level.

The need to protect the vulnerable IDPs and refugee groups who live in the camps under degrading conditions has been underscored by various local and international entities. In addition, the UN has repeatedly called for the repatriation of foreign children, women, and detained IS fighters. However, the international response has been far from satisfactory; on the contrary, only a very limited number of sporadic and case-by-case repatriations have been undertaken by countries such as Germany and France. Unless IS’s capacity to prey on the camps is curtailed, today’s children could turn into tomorrow’s second IS generation.

Two Possible Ways Forward for the EU

The drastic losses that IS faced in Syria and Iraq have not prevented it from mutating into a terrorist insurgent organisation that continues to propagate extremism and spread violence and instability across the Middle East. However, the battles that IS wages are not confined to the military, ideological, and economic realms. Rather, the infiltration and radicalisation of refugee camps comprise a palpable objective for IS to foster its potential in recruiting would-be fighters and maintain its social and ideological ties to the overcrowded camps and incarceration centres.

If the resurgence and resilience of IS and the continued turmoil in Iraq and Syria hamper the ability of those fighting the organisation to envision how and when to destroy it, then the EU must contrive a more realistic and operable policy. In short, this policy should aim to protect refugees and vulnerable groups in the camps in northeast Syria and Iraq via intensifying the EU’s humanitarian support within the camps by empowering the local authorities who administer these camps until a comprehensive EU blueprint for repatriating its citizens is ready.

More specifically, the immediate, short-term plan of the EU should be to mitigate the deteriorating conditions of everyone in the camps by improving the livelihood circumstances there via the provision of food, health services, clothing, shelter kits, child protection measures, juvenile rehabilitation facilities, and the like. Here, it is worth remembering that the EU continues to allocate large funds to achieve similar tasks and was recently the largest donor at the Brussels V Conference, where it assigned EUR 3.7 billion to support Syria and the neighbouring countries that host Syrian refugees. However, efforts should be intensified to meet the rising humanitarian challenges, especially given COVID-19 and the indefinite closure of al-Yarubiyya crossing point between Syria and Iraq due to the Russian veto that stopped the UN humanitarian agencies delivering aid from Iraq to Syria. Improving livelihood conditions is not unachievable, given the presence of many UN agencies, local and international NGOs, and other partners in the field with whom the EU can coordinate. The second pillar of this immediate plan could be to buttress the managerial and financial capacities of the local partners who maintain and safeguard the camps. In this regard, and especially in northeastern Syria, the EU should provide the Kurdish authorities with the needed expertise and resources to run the camps and detention facilities, in addition to, for instance, helping them overcome financial shortfalls affecting the number of guards and wardens they are able to employ.

In the meantime, the EU should prepare a mid-term plan for repatriating its citizens who have joined IS. This includes male IS fighters, their wives, and their children (most of whom were born in Syria or Iraq and are legally stateless). Of course, this is a significant challenge and may face obstacles due to political considerations and the individual legal systems of each EU member state, whereby ascertaining the involvement of the repatriated in terrorism, in addition to vetting and prosecuting them, are difficult tasks. However, with proper legal amendments and phase-based programmes for prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration, repatriation might be accomplished.

Finally, why would the EU adopt such a policy? The answer is, briefly, bifurcated: First, there is a normative imperative to uphold the ethical and human rights values of protecting vulnerable groups, including children and women. Second, repatriation of EU citizens and their families who joined IS cuts the latter’s chances of infiltrating the camps and spreading IS ideology. Of course, the repatriation of European IS members is not a panacea for radicalisation within the camps, especially when thousands of extremists are non-EU citizens. However, a move by the EU on this matter is indispensable for setting an international agenda on how to address the challenge of FTFs, and for making a solution to the local terrorists’ situation in the camps more discernable in the future. Forestalling a second generation of IS terrorism needs to be at the core of the EU’s plan, which should be implemented without delay.

Footnotes

References

Al-Ghadhawi, Abdullah (2020), ISIS in Syria: A Deadly New Focus, Washington, DC: Center for Global Policy, https://cgpolicy.org/articles/isis-in-syria-a-dead ly-new-focus/ (18 May 2020).

Al-Hashimi, Husham (2020), ISIS in Iraq: From Abandoned Villages to the Cities, Washington, DC: Center for Global Policy, https://cgpolicy.org/articles/isis-in-iraq-from-abandoned-villages-to-the-cities/ (5 May 2020).

Alsaafin, Linah (2020), Who is Cracking Down on Iraq’s Anti-Government Protesters?, in: Al Jazeera, www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/3/who-is-cracking-down-on-iraqs-anti-government-protesters (23 February 2021).

FATF (Financial Action Task Force) (2015), Financing of the Terrorist Organisation Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), Paris: FATF, www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Financing-of-the-terrorist-organisation-ISIL.pdf (13 January 2021).

Hassan, Hassan (2020), ISIS in Iraq and Syria: Rightsizing the Current ‘Comeback’, Washington DC: Center for Global Policy, https://cgpolicy.org/articles/isis-in-iraq-and-syria-rightsizing-the-current-comeback/ (18 May 2020).

Kanj, Sultan al- (2021), Islamic State Escalates Attacks in Syrian Desert, in: Al-Monitor, www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2021/02/syria-is-terrorism-war.html (16 February 2021).

Kenner, David (2019), All ISIS Has Left Is Money. Lots of It, in: The Atlantic, www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/03/isis-caliphate-money-territo ry/584911/ (24 February 2021).

Middle East Monitor (2021), UN Calls for 31,000 Foreign Children to be Repatriated from Syria, www.middleeastmonitor.com/20210211-un-calls-for-31000-foreign-children-to-be-repatriated-from-syria/ (19 February 2021).

ReliefWeb (2021), Iraq: Camp Closure Status, https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-camp-closure-status-date-14-january-2021 (19 April 2021).

REACH (2019), Camp and Informal Site Profiles – Overview Northeast Syria, Châtelaine: REACH Initiative, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/REACH_SYR_Factsheet_NortheastSyria_CampandInformalSiteProfilesRound6_AllProfiles_Oct2019.pdf (19 April 2021).

The Wilson Center (2019), Timeline: The Rise, Spread, and Fall of the Islamic State, www.wilsoncenter.org/article/timeline-the-rise-spread-and-fall-the-islamic-state (21 February 2021).

U.N. Security Council (2021), Twenty-Seventh Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2368 (2017) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities, New York: United Nations Security Council, https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/S/2021/68 (19 April 2021).

U.S. Department of Defense (2020), Operation Inherent Resolve. Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, Inspector General, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Aug/04/2002470215/-1/-1/1/LEAD%20INSPECTOR%20GENERAL%20FOR%20OPERATION%20INHERENT%20RESOLVE%20APRIL%201,%202020%20-%20JUNE%2030,%202020.PDF (19 April 2021).

U.S. Department of the Treasury (2019), Treasury Designates Key Nodes of ISIS’s Financial Network Stretching Across the Middle East, Europe, and East Africa, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm657 (7 January 2021).

Warrick, Joby (2018), Retreating ISIS Army Smuggled a Fortune in Cash and Gold Out of Iraq and Syria, in: Washington Post, www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/retreating-isis-army-smuggled-a-fortune-in-cash-and-gold-out-of-iraq-and-syria/2018/12/21/95087ffc-054b-11e9-9122-82e98f91ee6f_story.html (24 February 2021).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Almohamad, Selman (2021), Not a Storm in a Teacup: The Islamic State after the Caliphate, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, Hamburg : German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-72844-7

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.