- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Sustaining Civic Space in Times of COVID-19: Global Trends

GIGA Focus Global

Sustaining Civic Space in Times of COVID-19: Global Trends

Number 8 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3581

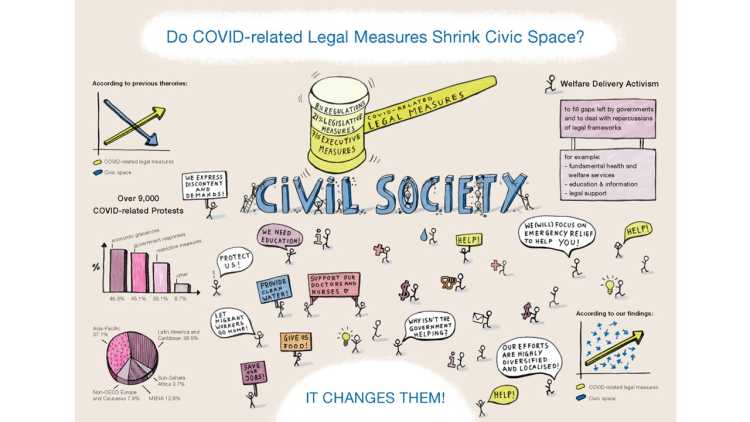

Autocrats worldwide have exploited COVID-19 and corresponding legal measures to curtail civil liberties. However, the health crisis and related socio-economic setbacks have also created needs-induced space, leading to a rise of civil society relief activism and propelling protests against dissatisfactory government responses. Rather than uniformly shrinking, civic space has often been sustained during the pandemic.

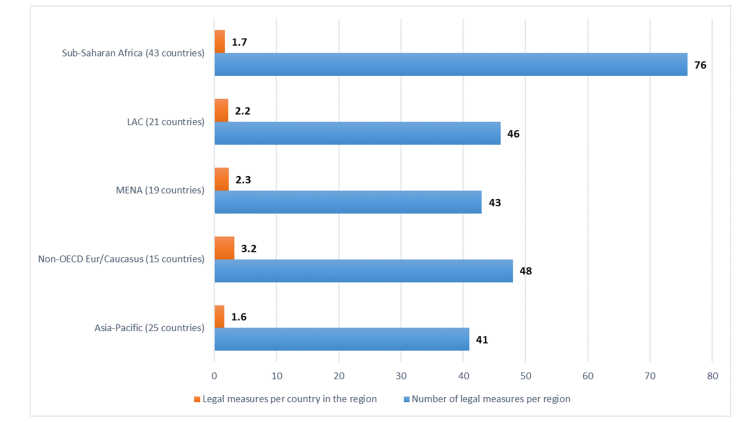

Civil liberties have further shrunk across the Asia-Pacific region, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), as 123 countries enforced 254 new legal frameworks related to COVID-19. The majority are executive measures that grant governments sweeping powers, leading to crackdowns on dissidents. Sub-Saharan Africa and non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus enacted the most legal measures, conducive to heightened repression.

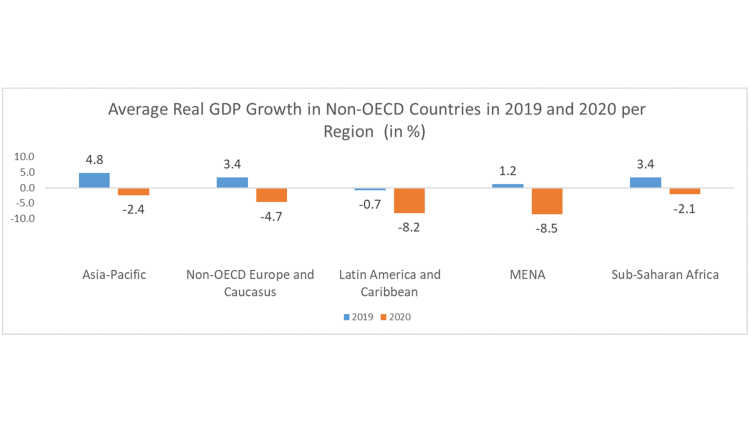

All five of these world regions saw the emergence of needs-induced space, illustrated by drastic declines in GDP growth, rising poverty, and increasing inequality.

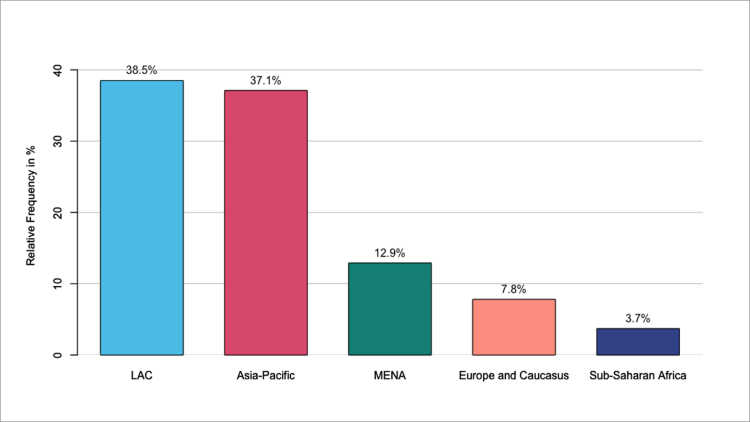

Despite (and sometimes because of) government efforts to weaponise COVID-19-related laws to erode civil liberties, protest activities have skyrocketed: demonstrators at more than 9,000 COVID-related protests have voiced their economic grievances and demanded better government responses. Most of these protests occurred in LAC and the Asia-Pacific, followed by MENA.

Civil society organisations (CSO) have enhanced their emergency relief, filling gaps left by governments. While carrying out such relief activism seems to have been easier in more democratic countries in LAC and the Asia-Pacific, CSOs have delivered aid and advocated for state provision in autocracies as well.

Policy Implications

European policymakers should set an example of how to implement democratic laws to contain COVID-19, and they should push back against the autocratic weaponisation of such laws elsewhere. European donor governments and political foundations should seek creative ways to support relief efforts by civil society that simultaneously address economic inequality and democratic governance, thereby enabling the sustenance of civic space.

Attacks on Civic Space

Since the early 2010s, scholars and international development practitioners have increasingly worried about “shrinking space,” broadly understood as the growing restriction of spaces in which civil society can operate (Poppe 2018). Shrinking civic space is closely related to “pushback” by autocratic governments against democracy aid and democracy more generally (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014: 48). The most commonly known expressions of shrinking civic space are “NGO laws” that limit the ability of non-governmental organisations (NGO) to register as such and thus obtain foreign funding. However, governments have also restricted civic space through a plethora of other legal measures that curtail freedoms of expression, association, and assembly. Since the onset of COVID-19, such attacks on civil liberties have further intensified, as non-democratic leaders around the world have instrumentalised measures that, while passed with the official purpose of curbing the spread of the coronavirus, have allowed these leaders to aggrandise their power and clamp down on oppositional civil society.

Concurrently, however, most governments in the Global South (Asia-Pacific, LAC, MENA, and sub-Saharan Africa) and in non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus have been overwhelmed by the public health crises and the socio-economic side effects of lockdowns and other restrictive measures. Consequently, the period from mid-2020 onwards has seen a marked rise in protest activity, some of which has been driven by COVID-19-related grievances. In addition, CSOs have stepped in to provide basic health and economic necessities. Based on an analysis of data from the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law’s (ICNL) COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) between April 2020 and February 2021, as well as on secondary literature and conversations with CSOs and experts, we show that while all five of the world regions named above have seen an increase in the number of legal frameworks that restrict civil liberties, such restrictions have often been ignored or contested via protests. In addition, civic space has been sustained by civil society-based relief activism in the welfare sector.

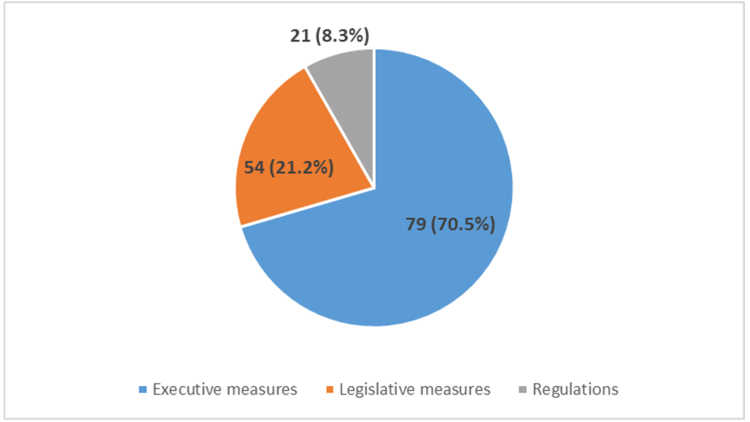

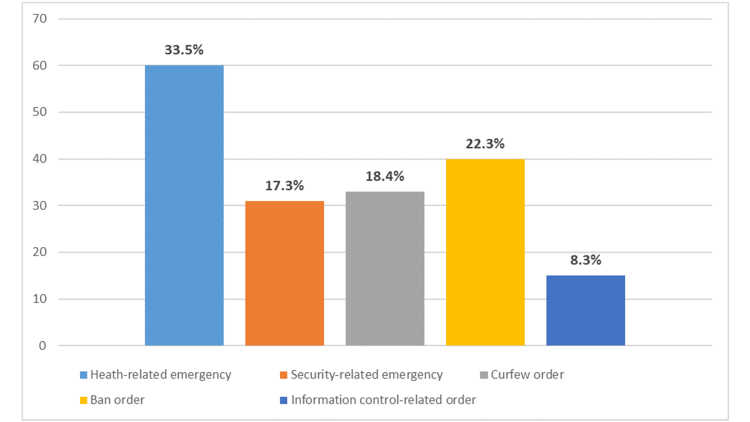

Civic Space in Light of COVID-19-related Legal Restrictions

The pandemic has given governments in autocracies and eroding democracies a pretext to restrict civil liberties and repress civil society critical of governments. According to V-Dem (2021: 24–25), freedoms of expression, assembly, and association declined significantly in 2020 compared to their status in 2019. Similarly, CIVICUS (2021) finds that more countries constricted rights relating to civic space in 2020 than in 2019. Our data shows that increasing numbers of legal restrictions that facilitated “lawfare” – the abuse of laws to criminalise oppositional civil society and generate a chilling effect to achieve self-censorship – have contributed to this disturbing development. Between April 2020 and February 2021, 123 countries in the Global South and non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus enacted altogether 254 legal frameworks. Of this number, the majority (179 legal measures, or 70.5 per cent) are executive orders or decrees passed without the involvement of parliaments. Of these executive measures, 33.5 per cent are related to health regulations to cope with the spread of COVID-19, including venue shutdowns and guidelines on disinfection and social distancing. However, approximately 17 per cent of these executive measures originate from war-time emergency decrees that associate the pandemic with a national security threat. As a result, the deployment of security forces in law enforcement has intensified, penalties against violators are harsh, and critics of government responses are branded as public enemies (CIVICUS 2021). Relatedly, across the five world regions investigated, executive orders ban public gatherings, impose curfews, and censor what the authorities deem “fake news.” In 91 countries with available information, we found that at least 80 legal measures were still active as of February 2021, with some emergency decrees extended several times. A case in point is Thailand, where the emergency decree has been extended 13 times despite the low rate of infections in 2020.

In terms of regional trends, the number of new legal frameworks interacts with regime type to indicate whether lawfare is being waged against civil society. Sub-Saharan Africa enacted the greatest number of decrees and legislations (76 legal measures, or 29.9 per cent), followed by non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus (48 legal measures, or 18.9 per cent). However, considering the number of legal measures per country in each world region, non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus featured the most prominently, with an average of 3.2 legal measures per country. In these two regions, autocracies and hybrid regimes such as Azerbaijan and Ethiopia have instrumentalised new COVID-19-related laws and decrees to crack down on the opposition. In Azerbaijan, at least six activists critical of government quarantine facilities and inadequate responses to economic setbacks were charged with breaking lockdown rules. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, a new state of emergency has granted the government sweeping powers to arbitrarily arrest journalists and human rights lawyers ostensibly for spreading “fake news” about COVID-19.

However, a lack of new legal measures taken by a given country or region does not automatically mean that repression is minimal. Take the Asia-Pacific, for example: The region saw the enactment of the least number of laws and decrees per country (1.6). But countries such as China and Bangladesh were able to rely on existing legal tools to quell critics. The Chinese government re-detained opposition figures upon their release from prison, on the pretext of quarantining them. During the so-called quarantines, some detainees were interrogated and kept incommunicado. In Bangladesh, the Awami League-led government abused the Digital Security Act of 2018 to arrest government-critical journalists, censor media, and consolidate government surveillance on the pretext of curbing coronavirus-related rumours.

This trend of legal repression further erodes civil liberties and intensifies conflicts between governments and civil society members who seek to voice grievances around COVID-19. In at least nine countries, including Cameroon, Cuba, Hong Kong, Niger, Russia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Uganda, and Ukraine, the ban on public gatherings provided a pretext for heavy-handed police crackdowns on protesters demanding more effective pandemic measures from their governments. Often protesters have faced multiple charges, from violating COVID-19 laws to terrorism and sedition (Human Rights Watch 2021). In Sri Lanka, for instance, the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP) led protests in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. The police responded with excessive force and justified that such measures were necessary to prevent the coronavirus from spreading (Kumarasinghe 2020). Similarly, when protests against police violence broke out in June 2020, Cuban authorities harassed and detained protesters, accusing them of “spreading the pandemic.” Although this pattern of repression is nothing new for Cubans, the COVID-19-related regulations have worsened crackdowns. But as these dynamics of restricted freedom of assembly suggest, the pandemic and its economic side effects also set the stage for civil society activism despite (and sometimes because of) curtailed liberties.

Needs-Induced Civic Space

According to gross domestic product (GDP) data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF Data Mapper 2021), all five world regions experienced a massive rise in socio-economic needs due to COVID-19 and the economic side effects of lockdowns. On average, countries in the Asia-Pacific region experienced a decline in real GDP growth of 7.2 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. However, there were marked differences within the region. For instance, while China’s real GDP growth dropped by only 3.5 percentage points, from 5.8 per cent in 2019 to 2.3 per cent in 2020, India’s real GDP growth declined by 12 percentage points, from 4 per cent in 2019 to -8 per cent in 2020. In non-OECD countries in Europe and the Caucasus, real GDP growth declined by an average of 8.1 percentage points during the same period. Similarly, LAC countries on average witnessed a loss of 7.5 percentage points. These figures, however, include the outlier of Venezuela, whose real GDP shrank by 35 per cent in 2019 and by another 30 per cent in 2020. In MENA countries, real GDP growth on average declined by 9.7 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. However, this calculation is somewhat distorted by Libya, whose growth declined by 72.9 percentage points, from 13.2 per cent in 2019 to -59.7 per cent in 2020. Sub-Saharan African countries on average lost 5.5 percentage points, which is significant particularly because most of them already had very low real GDPs when the pandemic hit.

According to World Bank (2021) estimates, the number of extreme poor globally increased from 644.7 million in 2019 to 737.6 million in 2020. Much of this increase happened in sub-Saharan Africa, where 474.8 million people lived in extreme poverty in 2020, up from 439.8 million in 2019. The Asia-Pacific region, LAC, and MENA also witnessed substantial rises in the number of extreme poor. Moreover, around the world COVID-19 and the economic consequences of lockdowns have deepened existing socio-economic inequalities, with marginalised groups such as slum dwellers and informal sector workers disproportionately affected. This emergence of needs-induced space has both driven protests and enhanced relief activism by civil society.

Protests and Civic Space

The economic impact of COVID-19 and dissatisfactory government responses to it have propelled protest activism; from this perspective, civic space did not shrink as expected. Both organised CSOs and informal groups organised and supported civic action in the form of protests. Instead of stepping back or backing down, civil societies expressed their concerns and made demands through mass mobilisation. According to the ACLED (2021) COVID-19 Disorder Tracker, this resulted in over 9,000 COVID-related protests in the five world regions investigated. In addition to these protests, there were even larger numbers of non–COVID-related protests. This shows once more how capable civil societies are of carrying out actions in the face of rigorous restrictions.

Economic grievances and underwhelming government responses to them were the main drivers behind COVID-19-related protests. The third most important driver was government-imposed restrictions. While these three drivers comprise the reasons for the majority of protests, only approximately 3 per cent of all protests are demonstrations against corruption and gender-based violence. In addition to the thematic focus of the protests, there are also clear trends regarding the frequency and distribution of protests among countries in the five world regions. Over three-quarters of all protests took place in LAC and the Asia-Pacific. The remaining quarter is divided among MENA, non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus, and sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 5 illustrates the relative frequency of protest events per world region in descending order.

LAC provides a representative picture of the distribution of protest drivers. Most prevalent were protests regarding economic grievances, as participants displayed their dissatisfaction with employment, trade, and/or the lack of compensation for lost income. Most affected in the region is Brazil, where protests have been erupting since the beginning of the pandemic. Citizens, particularly health workers, felt abandoned and took to the streets to express their discontent with the government and its neglect for the public health situation. The outraged crowds were joined by many in lockdown who banged pots and pans from their balconies. Protesters were disappointed in how the Brazilian government handled the pandemic and frustrated with the imposed restrictions (ACLED 2020).

A similar pattern can be detected in the Asia-Pacific. India’s 1,976 protest events make it the most protest-ridden country in the Global South. Most protesters were concerned with their dire economic situations and government responses. Particularly those who had migrated to the cities for work suffered greatly under the government mismanagement of the pandemic. Due to the lockdowns, many were not allowed to work or to return to their homes outside the cities. Without any income or government assistance, they had to fend for themselves, eventually taking to the streets. The case of migrant workers in India is not exceptional: many countries with weak governance and limited welfare saw their most vulnerable members of society enter hopeless situations.

Given that many governments in MENA implemented laws to control information, enforce curfews, and even grant the military more power, it is perhaps surprising that people still gathered to express their grievances. This was due in no small part to the important involvement of CSOs in the region. They were fundamental in organising, sustaining, and supporting protests of multiple causes. Accordingly, over 90 per cent of the protests in Turkey were organised either solely by CSOs or at least with CSO involvement. The government attempted to cut down CSO activities by banning them altogether. Yet, Turkey’s civil society fought back against the misuse of a COVID-19-related decree, and protests continued.

Despite (and sometimes because of) the large number of new laws in each country in non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus, protests occurred. Yet, these demonstrations differed from those in other regions in that the COVID-19-induced economic backlash played only a minor role. In fact, Ukraine experienced just a handful of protests with an economic component. When market vendors, lorry drivers, or farmers expressed their fear of unemployment and loss of income, their grievances also took aim at inefficient government responses or the lockdowns themselves. Overall, dissatisfaction with closures of markets, borders, schools, restaurants, gyms, movie theatres, and so on, dominated.

While sub-Saharan Africa has seen the most COVID-related laws and decrees of any region, it has had the smallest number of protests. South Africa is the only exception to this trend: Among other problems, its ill-equipped and understaffed health system suffered greatly from the flood of patients. Nurses, doctors, and other healthcare workers were left without any support, breaks, basic protective gear, or compensation for their work. On top of that, South Africa is one of the most socio-economically unequal countries, making its poorest citizens particularly vulnerable to the pandemic and its economic consequences. When people were out of jobs, water, and prospects for a better future, they organised marches to demand help from the government. The government leaving those demands unaddressed fuelled frustration and rage among the population, possibly contributing to the pro-Zuma riots in June 2020. Despite regional differences and varying opportunities to demonstrate, protests in the five world regions generally reflect people’s dissatisfaction with the limited ability of governments to tackle citizens’ basic needs in the face of the pandemic and the economic side effects of lockdowns.

Relief Efforts and Civic Space

Emerging needs-induced space similarly propelled a rise in CSOs’ relief activism, as governments in the Global South and non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus were often overwhelmed by the health and related socio-economic emergencies. Under these circumstances, civil society actors as varied as foreign-funded NGOs, community-based organisations (CBO), and local self-help initiatives stepped in to provide fundamental health and welfare services. Such relief efforts are hard to quantify due to their diversity and oftentimes highly informal and localised nature. However, qualitative research and international donors, including the United Nations, the European Union, and international NGOs, concur that in all five world regions, CSOs have played key roles in providing COVID-19 relief. Specifically, civil society groups have set up basic health facilities, distributed masks and sanitisers, educated citizens about the spread of the coronavirus and provided food packs and financial support to vulnerable groups. CBOs in particular have been instrumental in reaching marginalised social groups, owing to their flexibility and ties to local communities.

Civil society-based relief activism has been influenced by various factors, including the capacity of the state, the openness of the political system, and the willingness of governments to accommodate civil society. Accordingly, such activism seems to have been easier in relatively democratic countries in LAC and the Asia-Pacific, such as Argentina and Indonesia, where CSOs have sometimes cooperated with governments and complemented official relief efforts. Conversely, autocratic countries with relatively strong states, such as China, Vietnam, and the Gulf countries, have mostly sidelined or co-opted relief CSOs. Civil society-based relief initiatives have sometimes been suppressed in Russia and other non-OECD countries in Europe and the Caucasus. In sub-Saharan Africa, CSOs often seem to be at the forefront of relief efforts, filling the gaps left by often autocratic but nevertheless weak states.

By engaging in relief activism, CSOs in all five world regions have sustained and defended civic space against the odds. Specifically, civil society initiatives around the world have combined the delivery of social services with advocacy for strong welfare states and with monitoring government responses to COVID-19. In Brazil, diverse civil society actors united to provide emergency relief to marginalised groups. However, CSOs also countered the Bolsonaro government’s misinformation campaign, which downplayed the threat of the coronavirus, by conducting awareness campaigns online and offline. Similarly, social movements pushed local and national government entities to enhance their crisis responses and successfully lobbied the National Congress of Brazil to pass an emergency aid programme for informal workers (Abers, Rossi, and von Bülow 2021). In India, CSOs likewise played a key role in providing health and socio-economic support, while actively criticising government onslaughts on oppositional civil society on the pretext of pandemic control. In a context where Prime Minister Narendra Modi sought to instrumentalise COVID-19 to tighten his grip on power, the government’s Policy Commission ultimately had to thank civil society for its contributions to fighting the pandemic, acknowledging that many more people would have died without the support provided by CSOs (MJ 2020). In Turkey, where the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sought to curtail protests and critical civil society activism, CSOs continued to provide emergency relief. In so doing, they often worked alongside or in cooperation with municipal governments, including those led by the political opposition. In autocratic contexts, CSO engagement in emergency relief has even, at times, improved civil society–government relations. In Malaysia, for instance, the government first excluded CSOs from the delivery of aid to migrant and refugee communities. CSOs, however, ignored the restrictions and ultimately managed to develop partnerships with the government in this field (Nixon 2020).

Moreover, in all five world regions, human rights and other advocacy CSOs have engaged in relief activism, potentially politicising formerly apolitical spaces in welfare delivery and strengthening their legitimacy among local communities. In Thailand, for instance, student activists who protested against military rule in 2020 have provided aid to slum dwellers and other marginalised groups. Similarly, the fact that the pandemic has implacably exposed longstanding socio-economic inequalities has provided CSOs with an unprecedented opportunity to mobilise marginalised constituencies and push for strong welfare states. One Philippine CSO activist stated, “The identities of ordinary people bec[a]me very important as workers, as commuters, as consumers for health services. And these are important opportunities [for civil society activists] for having more conversations with them” (CSO roundtable, 1 June 2021). A CSO representative from India further elaborated that “state systems” were needed to ensure the “level of service delivery” required to fulfil citizens’ needs, while civil society initiatives also relied on support from the state. “It would be a mistake,” she added, “to think that that can happen without us [civil society] pressuring the state to put the resources where [they’re] needed” (CSO roundtable, 1 June 2021).

Concurrently, however, CSOs in the Global South and in non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus have also themselves been affected by the health and related socio-economic crises. Accordingly, civil society-based relief activism has also been influenced – and often limited – by the resources available to CSOs. CSOs in sub-Saharan Africa seem to have been especially hard-hit, given the context of massive poverty in which they operate. Moreover, in all five world regions advocacy CSOs have seen foreign support dwindle as donors have shifted their priority to purely humanitarian organisations active in COVID-19 relief.

What Can Be Done

As the COVID-19 pandemic is still ravaging global public health, containment measures that restrict contact, movement, and assembly are acceptable as long as their implementation is proportionate and temporary. However, many autocracies and eroding democracies are abusing COVID-19-related legal frameworks to consolidate executive power and further curtail civil liberties. When devising their own responses to the pandemic, German and European policymakers should keep demonstrating that COVID-19 can be dealt with democratically by subjecting all COVID-19-related measures to parliamentary control, civil society scrutiny, and the rule of law. Whenever possible, European policymakers, political foundations, and regional civil society networks should also push back against excessive laws and encroachments on civil liberties elsewhere.

In terms of European foreign and development policy, decision-makers should monitor COVID-related protests in the Global South and non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus to inform themselves about COVID-related grievances expressed by civil society and ordinary citizens in these parts of the world. In helping alleviate economic grievances, they should foster civil society initiatives in the field of emergency relief through financial support and capacity-building efforts. These may contribute to sustaining civic space even under adverse legal conditions. Relatedly, donors should also develop more flexible ways of supporting self-help initiatives and CBOs. While these are often unregistered and therefore unable to conform to formal donor requirements, they play crucial roles in reaching and mobilising marginalised communities. Concurrently, European donors should sustain and enhance their financial support to human rights and advocacy CSOs, as these frequently combine their COVID-19 relief with political advocacy and with pushing their governments to implement better crisis responses.

Footnotes

References

Abers, Rebeca Neaera, M. Federico Rossi, and Marisa von Bülow (2021), State–society Relations in Uncertain Times: Social Movement Strategies, Ideational Contestation and the Pandemic in Brazil and Argentina, in: International Political Science Review, 42, 3, 333–349.

ACLED see Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (2021), COVID-19 Disorder Tracker, https://acleddata.com/analysis/covid-19-disorder-tracker/ (8 September 2021).

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (2020), Pandemic and Political Unrest in Brazil and Nicaragua, https://acleddata.com/2020/07/23/pandemic-and-political-unrest-in-brazil-and-nicaragua/ (28 September 2021).

Carothers, Thomas, and Saskia Brechenmacher (2014), Closing Space: Human Rights and Democracy Support Under Fire, https://carnegieendowment.org/ 2014/02/20/closing-space-democracy-and-human-rights-support-under-fire-pub-54503 (28 September 2021).

CIVICUS (2021), 2021 State of Civil Society Report, https://civicus.org/state-of-civil-society-report-2021/ (2 September 2021).

Human Rights Watch (2021), COVID-19 Triggers Wave of Free Speech Abuse, www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/11/covid-19-triggers-wave-free-speech-abuse (2 September 2021).

IMF Data Mapper (2021), Real GDP Growth, www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD (6 September 2021).

Kumarasinghe, Kalani (2020), Sri Lanka Cracks Down on Black Lives Matter Solidarity Protest, in: The Diplomat, 11 June, https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/sri-lanka-cracks-down-on-black-lives-matter-solidarity-protest/ (28 September 2021).

MJ, Vijayan (2020), Dark Clouds and Silver Linings: Authoritarianism and Civic Action in India, in: Richard Youngs (ed.), Global Civil Society in the Shadow of the Corona Virus, Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 17–20.

Nixon, Nicola (2020), Civil Society in Southeast Asia during COVID-19: Responding and Evolving under Pressure, in: GOV Asia, Issue 1, September, Asia Foundation, https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GovAsia-1.1-Civil-society-in-Southeast-Asia-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf (9 June 2021).

Poppe, Annika Elena (2018), Wir müssen Shrinking Spaces besser verstehen, um dem Phänomen begegnen zu können, PRIF Blog, https://blog.prif.org/ 2018/08/23/wir-muessen-shrinking-spaces-besser-verstehen-um-dem-phaenomen-begegnen-zu-koennen/ (6 September 2021).

V-Dem (2021), Autocratization Turns Viral, Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg: Variety of Democracy Institute, www.v-dem.net/files/25/DR%202021.pdf (2 September 2021).

World Bank (2021), Updated Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty: Looking back at 2020 and the Outlook for 2021, World Bank Blogs, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty-looking-back-2020-and-outlook-2021 (6 September 2021).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Global

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Global

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Lorch, Jasmin, Monika Onken, and Janjira Sombatpoonsiri (2021), Sustaining Civic Space in Times of COVID-19: Global Trends, GIGA Focus Global, 8, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-76111-2

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.