- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Shrinking Spaces of Humanitarian Protection

GIGA Focus Middle East

Shrinking Spaces of Humanitarian Protection

Number 6 | 2018 | ISSN: 1862-3611

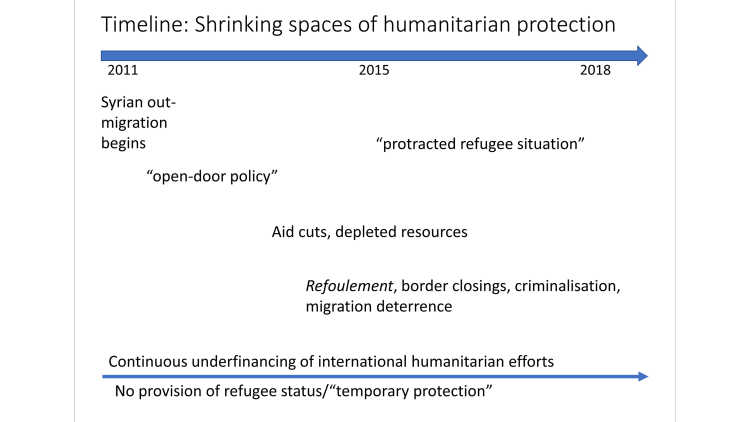

The Syrian crisis continues to kill and uproot. More than six million people have been internally displaced, while well over five million have fled the country – with the majority residing in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Like the spaces of civilian political agency in different parts of the world, ones of humanitarian protection also seem to be shrinking in some of the main refugee-hosting states in the Middle East too.

Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey have taken in millions of Syrian refugees since the beginning of the Syrian war. All three countries followed an open-door policy in the first phase of the Syrian conflict, assuming that the uprising would be as short-lived as its precedents in Tunisia and Egypt.

All three states have implemented a temporary protection regime, on the one hand providing fast and relatively non-bureaucratic refuge for Syrians fleeing while on the other excluding them from the special protection that comes with official refugee status.

All three states have experienced the shocking disinterest of the international community in the Syrian crisis, which became most apparent in the enduring and severe underfunding of aid efforts in the region.

All three states have since almost completely reversed their initial policies, with border closings, migrant criminalisations, and refoulement becoming regular practices. The movement out of the region and towards supposedly “safer” areas like the European Union has engendered a vicious circle of migrant deterrence and pressure on transit states, in which the refugees themselves are mere pawns.

Policy Implications

The continually progressing walling-off policies of the Global North increase the likelihood of Syrians staying in Jordan, Lebanon, or Turkey. Many would like to return home to rebuild their lives. It is, however, unclear how they will fare if Syria – where the war is still ongoing – is reconstructed in cooperation with the old regime and its cronies. Both internal and external actors need to recognise this in their efforts to reconstruct the state.

From Open Door to Deterrence

Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey have admitted hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees and provided them with temporary protection. Often, the Islamic umma was invoked to justify this “open-door policy”; what is more, the swift success of similar uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen can doubtlessly be considered a decisive factor for the three governments’ willingness to initially tolerate the inflow of Syrians. However the spaces of humanitarian protection provided by each of the three states began to shrink from 2014 onwards, when it became clear that the Syrian war was not going to be over any time soon, that the refugees were more likely to stay than to return, and that the international community was unwilling to share the burden – as was illustrated by both the severe underfunding of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and a strong focus on immigration deterrence. Internal dynamics – the escalation of the Kurdish issue and an attempted coup in Turkey, progressing political fragmentation in Lebanon, economic troubles in Jordan – also contributed to a decrease in support for hospitality towards Syrians.

With spaces of protection rapidly shrinking in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, more and more refugees would embark on the precarious journey towards Europe – leading to what has been dubbed the “European refugee crisis,” meaning a political crisis of asylum and immigration governance in the European Union. After a short humanitarian phase in (parts of) Europe in 2015, the Union has since returned to predominantly and increasingly hostile (im)migration and asylum policies – focusing mainly on the deterrence of immigrants and progressively externalising EU border protection to non-EU countries like Libya and Turkey. This development started a vicious circle with regard to migration and asylum policies in the EU and its southern and south-eastern neighbourhood: the more restrictive EU immigration policies became, the more pressure was being felt in sending and transit states to keep migrants “in the region” or “close to home” – and, meanwhile, the less protection has been available for refugees themselves.

Shrinking Spaces of Protection in Jordan

After the Syrian revolution quickly deteriorated into a violent civil war in 2011, a steady flow of Syrian refugees started to arrive in Jordan through the kingdom’s northern border from April of that year onwards. By June 2013, Zaatari – Jordan’s first and largest refugee camp for Syrian refugees – was hosting 120,000 people, making it one of Jordan’s largest urban centres. By the end of August 2013, more than 2,000 Syrian refugees were arriving per day in Zaatari alone. However, over 80 per cent of Syrians in Jordan have settled outside of the country’s refugee camps.

Today, Jordan hosts some 670,000 Syrian refugees according to the UNHCR. The monarchy under King Abdullah II, however, has stated that the number of Syrians living in Jordan is as high as 1.4 million, as it claims that approximately 750,000 Syrians had already been living in Jordan before 2011. While it is unclear how this figure was calculated and likely that it is too high, “the proportion of the Jordanian population that is comprised of Syrians is currently estimated to be between one-tenth and one-sixth” (Bank 2016: 3).

Refugees from the Syrian civil war are not the only group of refugees living in Jordan: more than half of the Jordanian population of around 10 million people are considered to have Palestinian roots. However official numbers of Jordanian citizens of Palestinian descent are rare, and estimates vary significantly, as the issue of Palestinians in Jordan remains politically sensitive. This is illustrated by the fact that the Jordanian government has refused entry to Palestinian refugees from Syria (PRS).

The kingdom’s hospitality towards refugees has provided the government with significant international support and financial aid. This also means that the number of refugees is a political as well as an economic issue for the government. It is, for instance, the declared interest of the Jordanian government to keep a significant number of refugees in the camps themselves, as these individuals are then considered more visible and a bargaining chip in negotiations for continuing aid flows (Bank 2016). This explains, at least in part, why estimates of Syrian refugees in Jordan vary widely depending on who is speaking about them and what the overarching agenda is.

There was historically no visa requirement for Syrians travelling to Jordan (and vice versa), so that crossing the border had for decades been a common practice among those living in the borderlands and those having business in either state – while strong family and clan ties connected the two peoples as well. At the beginning of the crisis, indeed, many Syrian citizens coming to Jordan stayed with host families, indicative of these strong pre-established ties; it was only later that Syrians began to rent their own spaces and/or were channelled to transit facilities and refugee camps. The first camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan, Zaatari, only opened in July 2012 – that is, over a year into the civil war. Overall, Jordan has established four official refugee camps for Syrians: Zaatari, Azraq, and the much smaller King Abdullah Park and Cyber City. Up until late 2014, residents could exit these camps through a sponsored bailout procedure; this policy has since been substituted by increasingly restrictive ones (Achilli 2015) which entail that most camp inhabitants have little opportunity to leave them legally, except by returning to Syria (Turner 2015).

Jordan is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and has no specific asylum laws. A memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Government of Jordan and the UNHCR from 1998 is the basis for the UNHCR’s work in the kingdom. It states that asylum seekers have the right to remain in Jordan for six months after recognition as such; during this time span, the UNHCR has to find a durable solution for them. Furthermore, Article 21 of the Jordanian Constitution prohibits the extradition of “political refugees” (Government of Jordan 1952). Article 4b of Law No. 24 of 1973 on Residence and Foreigners’ Affairs states that stateless persons, recognised refugees, and people without travel documents due to “reasons to be appreciated by the competent Jordanian authorities” shall receive international laissez-passers. Article 6 states that those entering the country as political asylum seekers outside of official border crossings shall report to a police station within 48 hours of their arrival (Government of Jordan 1973). Article 31 grants the interior minister the authority to determine whether a person who entered illegally will be deported, imprisoned, or accepted – on a case-by-case basis. The law does not, however, identify the conditions for being granted asylum.

Residency permits – which are a prerequisite for staying, receiving healthcare, working, and/or studying in Jordan – are usually valid for one year and thus need to be renewed regularly. They are rarely issued to asylum seekers, contributing to refugees working in the informal labour market (if at all). In sum, the legal situation of asylum seekers in Jordan is unclear and subject to internal political decision-making in the absence of overall binding legal regulations.

Up until late 2014, the Jordanian response to the Syrian refugee crisis was dominated by an understanding of incoming Syrians as “guests” and by an open-door policy. At the same time, refugees never received more than “temporary protection” – a revocable protection status that de facto means they do not have access to the official labour market or political participation (Turner 2015; Achilli 2015). Nevertheless, it indicates an immigration policy that was characterised by the expectation that the crisis in Syria was going to be temporary and by the perception of in-coming migrants as being non-threatening and prone to return to Syria sooner rather than later.

For the first three years of the crisis, registration with the UNHCR was the main and a quite reliable way for refugees to gain legal status as such (usually prima facie) and to access aid. Three years into the civil war, however, the continuous severe underfunding of international aid efforts for Syrians in the region converged with the Jordanian economy increasingly struggling to accommodate what started to look like a protracted refugee situation. Syrian refugees were struggling with the increasing cost of living in Jordan, with rapidly increasing rent prices, practically no access to the (official) labour market, and continuously depleting personal resources – not to mention the trauma of fleeing war and the loss of social and cultural ties. What is more, Jordanian host families were struggling with the continuing burden of additional household members; the Jordanian government grappling with the consequences of pre-existing economic difficulties as well as growing internal tensions over the question of the impact of hundreds of thousands of Syrians on the precarious political balance between different population groups within the country; and the international aid community dealing with a shocking disinterest in the Syrian crisis among the rest of the world, particularly the industrialised part of it, resulting in the continuous critical underfunding of aid efforts in the region.

The results were twofold: 1. Different aid agencies were compelled to severely and repeatedly cut food aid and other assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan (Stevens and Fröhlich 2015); 2. the Jordanian migration regime evolved towards deterrence and walling-off policies in order to curb further immigration, including border closings and the refoulement of refugees back to Syria. For instance, the Jordanian government introduced steep fees – for example for health certificates, as well as for other bureaucratic requirements – so that registering with the Jordanian police became much more difficult. What is more, Syrians who left a camp without permission and did not have bailout documentation were extremely vulnerable to refoulement and imprisonment (Lenner and Schmelter 2016). Those who left a camp unofficially after July 2014 could not register with UNHCR outside the camps or with police anymore, and were thus considered illegal immigrants – a complete reversal of previous policies. In sum, Syrian refugees have experienced continuing marginalisation and criminalisation in Jordan.

Shrinking Spaces of Protection in Lebanon

Lebanon hosts approximately one million refugees from the Syrian civil war, as well as some 450,000 Palestinian ones from Israel/Palestine, 50,000 PRS, and an estimated 40,000–50,000 refugees from Iraq (Lenner and Schmelter 2016). Syrian refugees first began to come to Lebanon, a state with strong pre-established social, political, and economic ties with their home country, soon after the conflict began; by early 2015, around one million Syrian refugees had registered with the UNHCR. In May of the same year, the Lebanese government asked the UNHCR to suspend the official registration of refugees – so that no newer data is available. It is likely that the number of Syrians in Lebanon has continued to rise since 2015, including unregistered refugees and migrant workers; as such, the number is in fact likely to be much closer to two million than to one million.

Even without recent official data, Lebanon is the country with the highest percentage of refugees globally relative to its native population of approximately six million people – a considerable burden for a state that has been struggling with institutional fragility, scarce resources, and, most importantly, a precarious sectarian balance – which has severely hampered state effectiveness. These internal difficulties are mirrored in the Lebanese state’s response to the Syrian crisis. In contrast to Jordan, where the government was a significant partner in planning the response to in-migration right from the start, the first three years of government response to the Syrian crisis in Lebanon were marked by a “policy of no-policy” (El Mufti 2014), which was in part due to more pressing issues at hand – like the difficulties arising from Hisbollah being part of government. In consequence, the UNHCR took the lead. However, Lebanon is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and lacks effective asylum legislation. Despite Lebanon’s MoU with the UNHCR (2003), registering with the UNHCR does not provide a reliable legal status to refugees in Lebanon, making them vulnerable to deportation and arrest. What is more, the historic experience of receiving hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees played a key role in the Lebanese government’s strong stand against establishing formal refugee camps, as Palestinian ones were important sites in the violent civil war of the 1970s and 1980s. This has led to very diverse living conditions among Syrians in Lebanon: some live in “informal tented settlements,” some in ruins or building shells or garages, while more than half rent regular accommodation (Lenner and Schmelter 2016). This illustrates the strong stratification of the Syrian populace in Lebanon, and the importance more generally of looking at Syrian refugees through an intersectional lens.

At the beginning of the Syrian crisis, the “policy of no-policy” meant that Lebanon let Syrians enter and move around the country quite freely. Unlike Iraqi refugees, who could rarely obtain a visa for Lebanon and thus predominantly entered the country illegally, Syrians benefited from the visa-free regime existing between the two states. Only in 2014 did the government try to reassert its position (as well as to reduce the number of incoming migrants) by introducing new visa regulations and new rules for receiving residency permits. In consequence, two categories of Syrian refugees were introduced effective from January 2015 onwards: Syrians who registered with UNHCR and Syrians who had a national “sponsor.” UNHCR-registered Syrians received a residency permit only if they signed a pledge not to work, and those with a sponsor required a guarantee that this person would cover their living expenses (Lenner and Schmelter 2016). The government also introduced high fees for renewing the residency permit. All of this has resulted in 74 per cent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon not possessing valid papers (as of May 2017, UNHCR 2018); the position of PRS is even more precarious. Not having valid papers means no access to health care and other services, and severe restrictions of mobility within Lebanon. The most recent UNHCR inter-agency report on the situation of Syrian refugees in Lebanon notes that 76 per cent are living in poverty, 53 per cent are living in inadequate shelter, and 91 per cent have experienced some level of food insecurity (UNHCR 2018). Also, certain municipalities introduced curfews for refugees from 2014 onwards.

Similar to Jordan, the concept of “temporary protection” was key in the Lebanese context for Syrian refugees. The status very much focuses on the temporariness of the respective refugee situation, assuming that the issue causing their displacement will be resolved and displaced persons will return to their homes eventually. Thus, temporarily protected people find themselves in a state of limbo and legal uncertainty. What is more, temporary protection in the understanding of the UNHCR is not limited in time, so that people with this status may well find themselves in an almost permanent situation of very few rights and almost no perspective. In Lebanon, even the provision of the prima facie status does not change this situation, as the Lebanese government has historically continued to treat incoming refugees as illegal migrants even after they had been provided the prima facie refugee status – as with Iraqis, for instance (Trad and Frangieh 2007). In a nutshell, spaces of protection have continuously shrunk for Syrian refugees in Lebanon since late 2014.

Shrinking Spaces of Protection in Turkey

Turkey currently hosts approximately 3.5 million registered plus an unclear number of non-registered Syrians, making it the most important host for Syrian refugees outside of their native country. Like Lebanon and Jordan, Turkey followed an open-door policy for the first few years of the Syrian crisis. Unlike the other two states, however, Turkey built 25 refugee camps in its south-eastern provinces alone and is the second-largest aid donor to Syrian refugees, a fact that has been praised both in- and outside of the country.

It is true that Turkey has put a lot of effort into addressing the Syrian issue, but most of its funds flow into the camps situated in the south-east, even though the vast majority of Syrians in Turkey reside in urban settings – most prominently in Istanbul. In fact, despite rising acknowledgement of the likely permanence of the Syrian refugee situation in the Turkish public and political discourse, aid structures for refugees remain fragmented and insufficient outside the camps; there is no coherent strategy and a significant gap exists between national policies and actual local implementation (or even just information flow). This is due to complex demographics, deep political polarisation, and increasing perceived security threats connected to the Syrian issue. Furthermore, the July 2016 coup attempt and its aftermath have deepened the general sense of unpredictability and precariousness of the future for both refugees and Turkish citizens alike.

Also, Turkey developed from a country of origin and/or transit to a host state only quite recently and at great speed, resulting in major political, social, economic, and cultural challenges. Turkey’s open-door policy was accompanied by a legal status for refugees comparable to that in Lebanon and Jordan. This status should not, however, be understood as a function of hospitality, but as a pointer to a severe lack of rights. The policy of temporary protection that had been in effect since October 2011 was encoded in national law in April 2013, specifically via Law No. 6458 on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP). LFIP includes three categories of protection:

a) refugee; b) conditional refugees (those awaiting resettlement, “transit refugees”); and, c) temporary or subsidiary protection.

It should be noted that while Turkey has signed the Geneva Convention of 1951, it also still adheres to the document’s original geographical delimitation – which states that the Convention only applies to asylum seekers from Europe. The first of the three status categories above is thus not available for Syrian asylum seekers under Turkish jurisdiction. In order to be granted temporary protection, meanwhile, foreigners must have been forced to leave their country en masse, must be unable to return to the one that they came from, and must be in urgent need of protection.

LFIP was implemented during the height of Syrian in-migration to Turkey, and can be assumed to have been influenced by the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights and the overall goal of EU ascension. Importantly, the principles and procedures regarding the law’s implementation were left open to determination by subsequent regulations. One of them is on temporary protection, which has been in force since November 2014 with the Regulation on Work Permits of Foreigners under Temporary Protection – which was eventually implemented in January 2016. The latter provides an opportunity for temporarily protected people to work in agriculture without work permits. The temporary protection regime also (in theory) grants unlimited free access to health care as well as to education – the latter by either joining the public education system or by enrolling in so-called Temporary Education Centres. Temporary protection is considered unlimited by the Turkish government, but it does not include any legal provision on how the temporarily protected can upgrade to permanent legal status.

Importantly, LFIP reshaped the administrative structure of migration affairs in Turkey: Police departments, which had formerly been responsible for distributing residence permits, were relieved of their duties and powers in favour of the Directorate General for Migration Management (DGMM), which is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior. Ever since, the DGMM has had the last word on every application for protection. However, the repeated reshuffling of officials responsible for devising policies and coordination has hampered the accumulation of know-how and development of suitable response strategies.

Conditional refugees and beneficiaries of the subsidiary protection status are usually obliged by the DGMM to reside in a designated province, and to report in at set intervals. Their place of residence is registered in the address registration system, and the information is passed on to the respective Provincial Directorate of Migration Management. In practice this means that Syrians have to report to the agency they originally registered with on a regular basis, while aid is also exclusively administered through this original place of registration. Someone who is registered in Hatay, for example, but now lives in Istanbul thus has to return to Hatay regularly to receive aid, a journey which is often impossible to undertake, however, due to a lack of necessary resources.

Access to the official labour market has been envisaged for Syrians in state policies, but is often not happening in real life. This is due to the continuously high Turkish unemployment rate (11.4 per cent), as well as to decreasing wages, especially in the agriculture and textile industries, and most importantly to the fact that both potential employers and Syrians alike have little incentive to apply for a work permit. A company can have a maximum of 10 per cent Syrian employees, and applicants have to have had a Turkish ID (kimlik) for at least six months prior and must also remain in the district where they first registered. To illustrate this point, only approximately 21,000 Syrians had received work permits in 2017. Access to health-care services and education has been deficient, too: approximately 40 per cent of Syrian children in Turkey (around 50 per cent of the Syrian constituency there are under the age of 18) are not enrolled in any educational institution. In any case, the Turkish education system was strained even before the Syrian influx and before the dismissal of tens of thousands of teachers after the attempted coup of July 2016.

Much like in Europe, xenophobia is on the rise in Turkey too. There is also some worry that Turkish political leaders may use the Syrian populace, which is mostly Sunni Arab, to transform Turkish national identity, consolidate power, and reframe Turkey’s role in the Middle East as more Arab, Sunni, and hegemonic. Many also believe that Syrians are strategically settled to weaken opposition voter blocs, representing a threat to the demographic balance as well as raising concerns about the gerrymandering of votes if Syrians were granted citizenship.

Similar to Jordan and Lebanon, Turkey has experienced negatively converging timelines: During the Syrian refugee crisis, the ruling AKP lost its parliamentary majority in June 2015 (with Syrians fearing a pro-Assad government taking office in Turkey) but then regained single-party rule in November of the same year. The ceasefire with the PKK disintegrated in July 2015, meanwhile, engendering a dramatic escalation of Turkish–Kurdish hostilities with also a rising death toll too. Islamic State conducted a number of attacks on Turkish soil, and the July 2016 coup attempt added to the perceived instability by creating emergency rule – which dramatically increased President Erdogan’s power. Hundreds of thousands of civil servants were dismissed or jailed, straining the state’s bureaucratic capacities. FETÖ- and PKK-related cleansings are pushing Syrians back on the political agenda, making refugees feel like a pawn in Turkish domestic and EU policies.

The Way Forward

In light of the respective country cases outlined above, it becomes clear that all three states started out with an open-door policy and implemented a temporary protection regime. On the one hand this provided fast and relatively non-bureaucratic refuge for Syrians fleeing the civil war, while on the other it excluded them from the special protection that comes with the official refugee status – de facto freezing them in legal limbo. All three states have experienced the shocking disinterest of the international community in the Syrian crisis, which became most apparent in the enduring and severe underfunding of aid efforts in the region. Turkey, as a rising economy, has been able to provide quite a bit more protection than Jordan or Lebanon have, but could still use these efforts for its own political advantage.

With the civil war raging on much longer than expected, both hosting states and Syrians hoping for a return home have adjusted to the increasingly protracted situation. Syrians who could afford it attempted to find refuge in Europe, with thousands dying on the perilous journey. Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey almost completely reversed their initial policies in late 2014/early 2015, meanwhile, after years of receiving and caring for Syrian refugees. All three states began to emulate the long-standing migration-deterrence policies of the Global North, with border closings, migrant criminalisations, and deportations becoming regular practices; from a postcolonial perspective, one could see this as a case of perfect mimicry in Homi Bhabha’s sense (Bhabha 1994). In consequence, the spaces of humanitarian protection available to Syrians shrank markedly in all three states.

Even though this development is another instance of shrinking spaces of civilian agency (Poppe and Wolff 2017), with refugees becoming mere pawns in national, regional, and international politics, it is also one that has not been sufficiently reflected in the debates on this issue. An important point to consider for actors trying to solve the Syrian refugee issue is how efforts to “reconstruct” the Syrian state will impact their situation both in the very states in which actors from the Global North are advocating they should stay, and as potential returnees. As the spaces of protection for refugees continue to shrink both within the region and beyond, return is increasingly presented as the most viable option for Syrians. At the same time, it is entirely unclear how they will fare if reconstruction is happening in cooperation with the very actors that drove them out of the country in the first place.

Footnotes

References

Achilli, Luigi (2015), Syrian Refugees in Jordan: A Reality Check, Migratio Policy Centre, EUI, http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/34904/MPC_2015- 02_PB.pdf?sequence%C2%BC1.

Bank, André (2016), Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Between Protection and Marginalisation, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/ syrian-refugees-in-jordan-between-protection-and-marginalisation.

Bhabha, Homi K. (1994), The Location of Culture, Reprint, London: Routledge.

El Mufti, Karim (2014), Official Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon, the Disastrous Policy of No-Policy, Civil Society Knowledge Centre, https://civilsociety-centre. org/paper/official-response-syrian-refugee-crisis-lebanon-disastrous-policy-no-policy.

Government of Jordan (1952), The Constitution of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, www.refworld.org/pdfid/3ae6b53310.pdf.

Government of Jordan (1954), Law No. 6 of 1954 on Nationality, www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4ea13.html.

Government of Jordan (1973), Law No. 24 of 1973 on Residence and Foreigners’ Affairs, www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4ed4c.html.

Lenner, Katharina, and Susanne Schmelter (2016), Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Lebanon: Between Refuge and Ongoing Deprivation?, in: IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook, 122–126, Barcelona: European Institute of the Mediterranean.

Poppe, Annika Elena, and Jonas Wolff (2017), The Contested Spaces of Civil Society in a Plural World: Norm Contestation in the Debate about Restrictions on International Civil Society Support, in: Contemporary Politics, 23, 4, 469–488, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1343219.

Trad, Samira, and Ghida Frangieh (2007), Iraqi Refugees in Lebanon: Continuous Lack of Protection, in: Forced Migration Review, Special Issue, 35, 35–36.

Turner, Lewis (2015), Explaining the (Non-)Encampment of Syrian Refugees: Security, Class, and the Labour Market in Lebanon and Jordan, in: Mediterranean Politics, 20, 3, 386–404.

UNHCR (2018), Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (2017-2020) Annual Report - 2017, Inter-Agency Coordination Lebanon, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/ download/64657.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Fröhlich, Christiane (2018), Shrinking Spaces of Humanitarian Protection, GIGA Focus Middle East, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-61075-9

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.