- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Colombia: Between the Dividends of Peace and the Shadow of Violence

GIGA Focus Latin America

Colombia: Between the Dividends of Peace and the Shadow of Violence

Number 2 | 2020 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Post–peace accord Colombia is full of paradoxes. Progress in political participation, in inclusion, and heightened social mobilisation are unfolding against a backdrop of persistent violence and insecurity. While the end of the war with the FARC-Ep has enabled relevant democratic advances, the lack of implementation regarding the peace accord as well as the current government’s policies raise serious concerns about the prospects for peace and democracy.

The peace agreement between the state and FARC-Ep guerrillas has been a contested subject in Colombian politics. Although the transition has been far from smooth, it has enabled opportunities for peacebuilding and shifted the public debate towards issues such as inequality and corruption.

Amid this transitional context, President Iván Duque’s government has not managed to develop a political project according to the post-accord scenario. Unable to either please the most radical factions of his right-wing party, Democratic Centre, or to build a government in line with the demands of the Colombian citizenry, Duque’s approval rating has plummeted to just 23 per cent.

Social discontent manifested on the streets in the form of mass demonstrations at the end of 2019. While the demands made point to long-standing problems, the shortcomings of the current government have led to discontent being channelled through the figure of Duque specifically. A salient trait of the protests is the participation of the urban, middle class, and youth.

Meanwhile, violence has not come to a halt. A reconfiguration of non-state armed actors and the emergence of further violence are taking place in different localities against the backdrop of the structural factors that the peace process never resolved. The Colombian government has also failed to protect the lives of social leaders and former FARC-Ep combatants.

Policy Implications

The response of the government to citizens’ demands raises serious concerns about both the governance capabilities of President Duque and the repercussions thereof for the already undermined credibility of the Colombian state and its democratic institutions. Complicating matters, the half-hearted implementation of the peace agreement and the persistence of violence suggest a grim outlook. In the face of all this, it is crucial to support the efforts of actors committed to peacebuilding endeavours.

An Incomplete Peace

In December 2016 the Colombian government signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC-Ep), bringing an end to its 50-year war with the largest rebel group in the country. Given its comprehensive and innovative approach, the accord was praised by some sectors of Colombia society, by scholars, and by the international community. Undoubtedly, the agreement constituted an outstanding development in Colombia’s ongoing endeavours to end violence and build a strong democracy. Nonetheless, it has not since brought the peace that many Colombians expected it would. Positive developments such as disarmament of the FARC-Ep, its transformation into a political party, the creation of local development programmes with a focus on territorial peace, and progress on transitional justice contrast with the intensification of violence in certain areas of the country, the killing of social leaders and former combatants, and bitter turf wars among a plethora of criminal groups. Three years on from its signing, the assessment of the peace agreement yields a mixed view thereof.

As in any post-accord scenario, implementation has been a matter of contestation among the various stakeholders involved. However, particular political developments have made the situation even more challenging. The rejection of a first version of the peace deal by a slight margin in the plebiscite held in October 2016 marked a major blow to the process. Even though both the government and the FARC-Ep promptly agreed on introducing relevant adjustments and signed a second version that was ratified by Congress, the legitimacy of the accord was inexorably undermined. Discontent with the agreement was capitalised on by political factions, particularly former president Álvaro Uribe and his political party Democratic Centre (Centro Democrático, CD) that opposed the peace process from the outset. Under the promise of introducing significant changes, CD’s candidate, Iván Duque, was elected president in 2018. Duque’s rise to power hampered the prospects for a thorough enforcement of the agreement.

In contrast to traditional disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) models that conceive former combatants’ reintegration as an individual process, FARC-Ep envisioned their transition as being a collective endeavour. Thus, instead of using terms such as “demobilisation” and “reintegration,” they talked about “the [dismantling] of armed structures while remaining as a grouping” and “the reincorporation to the political system, instead of a reinsertion into the society” (Zambrano Quintero 2019: 46). Such semantic distinctions aimed at highlighting that the peace process marked the end of the FARC-Ep as a military apparatus but not as a political organisation and collective actor. In line with this, the group transitioned from being the FARC-Ep to become the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (Fuerza Armada Revolucionaria del Común, FARC) (Nussio and Quishpe 2019).

In the initial phase, FARC laid down its weapons, launched the reincorporation process, and created a pollical party. With the assistance of the United Nations, arms were collected and decommissioned. FARC handed in a total of 8,994 weapons and more than 1.7 million rounds of ammunition (UN 2017). In late 2016, FARC mefmbers moved to provisional settlement areas consisting of encampments where the troops were stationed. Later, some of these sites (plus other localities) were adapted as “Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces” (Espacios Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación, ETCRs). Problems and delays in the allocation of resources and infrastructure provision have prompted former combatants to move out of the ETCRs. To date, 12,940 persons are in the process of reincorporation – of these 9,275 live elsewhere to the ETCRs, 2,946 still dwell in them, while there is no official information on the whereabouts of the remaining 719 individuals (ARN 2020). The insecure situation of former combatants is a major concern, as some 173 have been killed since the signing of the agreement. Just weeks ago, heightened violence pushed the members of an ETCR in the municipality of Ituango (Department of Antioquia) to make the decision of leaving the space and relocating into a yet-to-be-decided new area.

Whereas the vast majority of former combatants are fully committed to the peace process, a small share refused to lay down their weapons prior to the peace deal being struck. The persistence and emergence of new dissident groups is a phenomenon that has been increasing ever since. Rearmed factions add to the constellation of remaining warring parties. In what constitutes one of the heaviest blows to both the FARC as a political organisation and to the peace process, after fleeing to an unknown location – most likely Venezuela – senior FARC commanders released a video in August 2019 announcing their decision to take up arms again. A group formed of lead negotiators for the FARC-Ep during the peace talks – such as Luciano Marín, known as Iván Márquez, and Seuxis Pausias Hernández, known as Jesús Santrich, among other prominent leaders – called for a new era of rebellion and urged former comrades to join them.

For the government, both the dissidents’ and the rearmed factions’ main motivation here is the capture of the rents from illegal economies such as drug trafficking and clandestine gold mining. In contrast, rearmed combatants argue that it is the government’s “betrayal of the Havana Peace Agreement” that has prompted their return to war. While criminal economies certainly do play a crucial role and will keep shaping the dynamics of violent conflict to a significant extent, to fully discard the political aspects would be a mistake. Historical mistrust of the Colombian state aroused suspicion among some FARC-Ep combatants at the time about the possibilities of reaching an agreement, and also its subsequent implementation. In this regard, the lack of compliance by the Colombian government and the animosity towards the agreement demonstrated by Duque’s administration have fuelled disenchantment among ex-FARC-Ep fighters – and being taken to validate their decision to renounce the process.

FARC’s current situation illustrates the struggle of former guerrillas to maintain their unity and cohesion in post-accord settings. Although the majority remain committed to the peace process, the exacerbation of internal tensions with the split in leadership between those remaining wedded to the ongoing process and those seeking to rearm – alongside the complex and challenging circumstances found at both the local and national levels – have the potential to jeopardise the future of the FARC as a political project, and the reincorporation of former combatants (Nussio and Quishpe 2019).

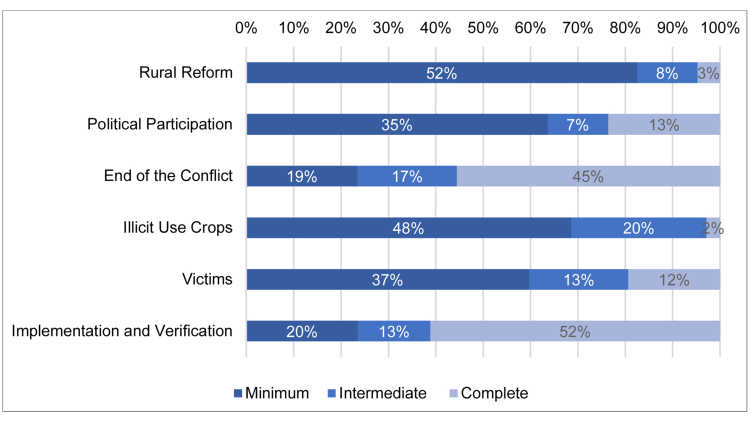

The end of the FARC-Ep as an insurgent group is at the core of the peace agreement, but the scope of it is nevertheless broader – as it also includes measures on comprehensive rural reform, political participation, ending the conflict, transitional justice, and drugs policy. Figure 1 below displays the progress made in the implementation of each of the six points of the accord up to April 2019 (Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies 2019). Whereas those areas related to the disassembling of the guerrilla group’s military structure report the highest degree of progress, where little advancement has been made is in regard to structural transformations – for instance, measures aimed at tackling rural marginality and underdevelopment. While it is true that the current government has no interest in pushing structural reforms, the lack of engagement with these kinds of changes goes back to the administration of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018) – whose readiness to foster FARC-Ep’s disarmament and reincorporation sharply contrasted with his reluctance to engage with deep-rooted reforms. Although solving all social problems was clearly beyond the reach of the agreement, the shortfall in the implementation of structural reforms endangers one of the most valuable contributions thereof: its addressing of the socio-economic and political problems that lie at the heart of the (re)production of violence in Colombia.

Despite its flaws, the peace deal has still had a significant political impact. At the local level, communities have benefitted from the ceasefire, with the end of armed confrontation. Likewise, through the advancing of notions such as “territorial peace,” the agreement has enabled new channels of participation for communities to emerge and has fostered the strengthening of local democracy. Post-accord Colombia may not be the one that the most optimist supporters of the peace process envisioned; however, the end of the war with the FARC-Ep would usher in a new phase in Colombian politics regardless.

The Persistence of Violence and Insecurity

While the peace accord brought an end to the state’s conflict with one of the largest armed groups in Colombia, it regrettably has not meant the end of violence per se. In fact, struggles over the accord’s implementation have unfolded against the backdrop of new waves of violence emerging in many areas of the country – notably in zones that were formerly under FARC-Ep control, and where drug crops and illegal mining are concentrated. Social movement and grass-roots leaders are, along with ex-FARC-Ep combatants, the main targets of violence, being those whose protection and living conditions are at the core of the peace deal. Although there is variation in the statistics reported by different organisations, the death toll between 2016 and 2018 amounted to at least 600 victims (Rozo and Ball 2019) – to which at least 108 murders in 2019 alone must also be added (UN 2020). Likewise, the return of massacres and forced displacement evokes the worst times of violence.

Rebel forces such as the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) and Popular Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Popular, EPL) along with organised crime and successor paramilitary groups make up the complex constellation of armed groups active on the ground. The stepping back of the FARC-Ep left a power vacuum that these groups have tried to fill, leading to the reconfiguration of patterns of territorial control, disputes, and criminal alliances. State institutions have been unable to establish their authority and grant security to populations in the areas afflicted by enduring violence. Yet, to portray the current situation as a problem restricted merely to a weak state incapable of dealing with competing armed actors would be profoundly misleading. Shady alliances with criminal groups and the reliance of the state and regional political and economic elites on non-state armed actors, notably paramilitary groups, form part of the breeding ground for violence. Although the state denies that paramilitary violence persists, groups of such ethos continue to curtail the implementation of the agreement by targeting former FARC combatants, social leaders, and marginalised communities. Enduring violence therefore not only results from entrenched criminal economies but constitutes also a resource that sectors whose interests would be undermined by structural reforms use against marginalised groups otherwise empowered by the peace process.

The current situation in Venezuela and its impacts in Colombia compound the violence and insecurity witnessed. On the one hand, Venezuela became a safe house for the ELN and EPL. Support from Nicolás Maduro’s government has fostered favourable circumstances for the ELN’s expansion and strengthening in both countries. On the other hand, the massive influx of Venezuelan immigrants to Colombia, totalling around 1.8 million people, has led to a humanitarian crisis and strained the already limited resources of the state to provide assistance. Contrary to the media depictions of migrants as a source of insecurity and crime, they have actually become victims of forms of violence and criminality already alive and well in Colombia.

New Scenario, Old Strategies

When Duque came to power in August 2018, he found himself in a tricky position. Having been elected on a platform largely based on opposition to the agreement, his party expected him to introduce substantial modifications to what they consider flaws in the deal. However, the implementation of the agreement was already underway by then. An encompassing institutional structure had been created, its cornerstone being a set of legal instruments enshrined in the Constitution. Further complicating matters, Duque’s lack of support from the majority of Congress represents a significant limitation to his endeavours to alter the peace deal. Unable to change the path set by the accord, Duque’s policies have been characterised by continuous contradictions and a stubborn insistence on governing with the same strategies of his mentor, former president Uribe. This has not only hurt the peace process’s prospects, but also undermined the government’s capacity to tackle the country’s most pressing problems.

The dissonance between the government’s articulated attitude towards the peace agreement in the international arena on the one hand and in the domestic context on the other is one of the clearest instances of these contradictions. The international community backed the peace process from the outset, and has been closely involved in the accord’s implementation. Likewise, expectations of peace in Colombia improved the country’s economic profile and fostered the interest of international companies and investors in doing business there. Aware of this reality, Duque has continuously expressed his support and commitment to the peace process in international fora.

However, his pro-peace discourse rings hollow on the domestic stage. The government has sought to dismantle core aspects of the agreement, and set obstacles to its implementation. Its actions range from overt initiatives to more subtle gestures and symbolic actions. Among the most visible is the government’s crusade against the transitional justice system, notably the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (Jurisdicción Especial de Paz, JEP) that, according to its detractors, provides impunity for the FARC. At the beginning of 2019, Duque refused to sign the bill establishing the JEP’s legal framework – despite having already been approved by Congress and the Constitutional Court. Instead, in a controversial move, he objected to six important articles of the draft law and sent it back to Congress. In the end, both Congress and the Constitutional Court rejected the objections – leaving Duque with no option but to sign the bill. More subtle but equally perilous are the budgetary cuts and insufficient provision of personnel and political support for the various agencies in charge of implementing the accord.

These actions have been framed by an overarching narrative that denies the existence of an armed conflict and posits instead that the problem of violence in Colombia is about a state beset by terrorism and criminality. In concordance with this, Duque has opted for a hard-line approach in areas such as security and anti-narcotics policies. His security policy resembles former president Uribe’s “Democratic Security” policy in many aspects. In this regard, human rights organisations and civil society actors have voiced their concerns about some of the measures adopted by the military, such as performance assessment based on deaths in combat – meaning the body count – that might lead to the repetition of infamous episodes of extra-legal killings – known as “false positives” (Flórez 2019).

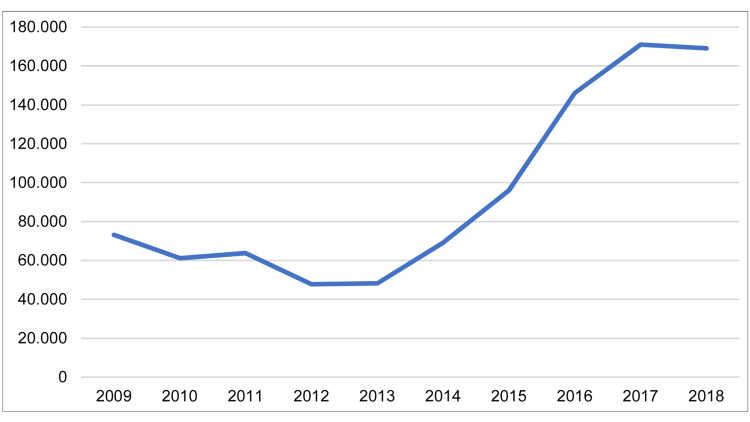

As Figure 2 below shows, the volume of coca crops grown in Colombia has skyrocketed in recent years. The peace accord contains a whole section dedicated to the issue of illicit drugs that emphasises voluntary crop-substitution programmes and the improvement of underdeveloped local conditions. Going against this, and in line with the demands of the current United States administration, Duque decided to strengthen forced-eradication measures – with the increase of manual eradication, along with the return to aerial-spraying campaigns using the herbicide glyphosate. Aerial spraying had until then been suspended in Colombia since 2015 over health concerns. Likewise, the Constitutional Court set restrictions on the use of glyphosate from aircraft. Duque asked the Court to ease the measures in order to allow more spraying, but the Tribunal ruled to retain the restrictions.

In pushing for this agenda, Duque has turned a deaf ear to citizens’ demands, further fuelling dissatisfaction. The war hit rural areas hardest, but problems such as poverty, inequality, corruption, and a lack of opportunities also affect people in the cities. For years, the impact of these issues was overshadowed by the immediacy of the war. Additionally, the FARC-Ep functioned as an all-purpose bogeyman that the government could invoke to explain away social discontent. This notion was central to the Democratic Security policy, the cornerstone of the – arguably extremely successful – political project of Uribe.

With the peace process, however, this all-encompassing narrative lost its grip. In this context, diverse citizen agendas have gained visibility. Notably, the demands of the urban and of youth, whose main concerns relate more to socio-economic conditions than to the fight against an alleged terrorist threat. The exhaustion of this model and Duque’s inability to craft a government in line with the new circumstances has led to the noted sharp increase in his unpopularity, which reached 73 per cent in February 2020 (Semana 2020). In the face of this, the streets have become the outlet for expressing citizens’ discontent.

Social Mobilisation and Protests

The national strikes and ensuing demonstrations of late 2019 shook Colombian citizens and political elites alike, as the country had not witnessed such mass protests since 1977. These mobilisations brought forth diverse sections of Colombian society articulating a wide range of demands, from addressing the inadequate implementation of the peace agreement to taking action against deteriorating socio-economic conditions, the rejection of labour and pension system reforms, as well as the expression of concerns about the environment. While these demands point to long-standing problems, the shortcomings of the current government have led to discontent being channelled specifically through the figure of Duque.

In the face of such protests, the government’s initial reaction was marked by the attempts to discredit the motives behind the national strikes – arguing supposed connections to left-wing extremists and Venezuela’s government, and denying that the government was planning any reform. Later, Duque accused the leader of the opposition, Gustavo Petro, of being behind the strikes in a move supposedly aimed at destabilising Duque’s government and Colombian democracy. Alongside its efforts to generate suspicion about the motives and legitimacy of the mobilisations, the government relied also on the deployment of anti-riot police and military units to control the demonstrations and patrol the streets. Excessive use of force by the security apparatus resulted in the deaths of at least three citizens, while hundreds were injured (Deutsche Welle 2019). The dismissive and violent response from the government led to citizen outrage and even greater support for the strikes. In the face of this, Duque adopted a seemingly more conciliatory stance and called for the start of “a national conversation.”

Protests in Colombia are certainly connected to the broader wave of demonstrations taking place throughout Latin America. Three decades after the “third wave of democratisation,” citizens are unsatisfied with their political leaderships and a democracy that does not live up to expectations; Colombia is no exception. Yet, the enabling conditions of the protests are to be found in the domestic context and in the changes that the end of the war against the FARC-Ep brought about. On the one hand, FARC guerrillas ceased to be at the heart of national concerns and politics. Instead, issues such as corruption and socio-economic conditions gained in relevance (El Tiempo 2018). On the other hand, the hackneyed argument that such protests were instigated by the guerrillas and terrorists became obsolete with the peace process, opening up venues for heightened social mobilisation (Botero and Otero 2019).

As 2019 came to an end, the waves of protest lost their momentum – while the leaders of the strikes have been unable to create a coherent programme to underpin negotiations with the government. However, in the course of 2020 so far, government spokespersons have timidly announced their intention to undertake reforms in areas such as the labour market and pension system, as noted underlying facets of protestors’ complaints – so it is to be expected that if the government does indeed go ahead with its proposed plans, citizens will return to the streets once more.

An Uncertain Road Ahead

The end of war with one actor is not tantamount to peace. This is especially true in contemporary Colombia, where the variety of armed groups and manifold linkages between order, the state, and violent entrepreneurs conjure a formidably complex setting. Undoubtedly, the peace agreement has contributed to peacebuilding and democracy. Nonetheless, structural problems remain and are igniting new waves of violence. Complicating matters, the potential and promises engendered by the accord’s comprehensive approach will not be fully developed as things stand given the current political set-up has curtailed the possibilities for its implementation. Given the impossibility of realising the accord entirely as envisaged, it is thus necessary to devote effort to the most relevant and strategic aspects of it. In particular, the reintegration of former combatants, programmes of local development, and transitional justice.

However, armed violence is not the only expression of social conflict. Current government policies and their disconnect from the citizenry’s demands are fuelling social unrest. The repressive means employed by the government during the recent waves of protest raise concerns about the effects thereof on democracy and the legitimacy of state institutions in a moment where the strengthening of trust between the state and citizens is of paramount importance.

In the face of this, support being given to state institutions, political actors, and communities committed to peace is crucial. Peacebuilding efforts in Colombia have been sustained by committed domestic actors at the national and local levels, as well by the international community. Germany and the European Union have contributed significantly to the peace process since the beginning. Amid the mutated forms of armed conflict and violence now being witnessed, international partners are being called to play a significant role – that by backing up the work of the institutions created within the framework of the peace agreement and of local development projects, assisting in the provision of humanitarian aid for Colombian victims of violence and Venezuelan refugees alike, and supporting processes and initiatives to make civil society organisations in both rural and urban areas more influential. Factors such as Colombia’s positive economic outlook and the end of the war with one of the country’s historically most powerful guerrilla movements might suggest a story of success. However, failing to protect and nurture the achievements of the peace agreement will only continue to contribute to renewed cycles of violence and criminality.

Footnotes

ARN (Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización) (2020), La Reincorporación en cifras, Bogotá: Agencia para la Reincorporación y la Normalización.

Botero, Sandra, and Silvia Otero (2019), El dividendo agridulce de la paz truncada, CIPER Académico, https://ciperchile.cl/2019/11/25/el-dividendo-agridulce-de-la-paz-truncada/ (5 February 2020).

Deutsche Welle (2019), Gobierno informa de tres muertos por protestas en Colombia, www.dw.com/es/gobierno-informa-de-tres-muertos-por-protestas-en-colombia/a-51373184 (12 February 2020).

El Tiempo (2018), Corrupción, principal problema del país según encuesta Gallup, www.eltiempo.com/politica/gobierno/corrupcion-principal-problema-del-pais-segun-encuesta-gallup-305070 (3 February 2020).

Flórez, Alicia (2019), Colombia retrocede a regañadientes en controversial plan militar, https://es.insightcrime.org/noticias/noticias-del-dia/nueva-sombra-de-falsos-positivos-se-posa-sobre-el-gobierno-de-colombia (13 February 2020).

Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (2019), State of Implementation of the Colombian Final Accord. Executive Summary, South Bend.

Nussio, Enzo, and Rafael Quishpe (2019), La fuerza centrífuga del posconflicto: las FARC-EP, entre la unidad y la desintegración, in: Angelika Rettberg and Erin McFee (eds), Excombatientes y acuerdo de paz con las FARC-EP en Colombia, Bogotá: Universidad de Los Andes, 163–188.

Rozo, Valentina, and Patrick Ball (2019), Killings of Social Movement Leaders in Colombia: An Estimation of the Total Population of Victims-Update 2018, https://hrdag.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/2019-HRDAG-killings-colombia-update-english.pdf (5 February 2020).

Semana (2020), El presidente Duque, con la aprobación más baja en sus 19 meses de mandato, www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/encuesta-gallup-imagen-de-duque/653842 (1 March 2020).

UN (2020), El 2019, un año muy violento para los derechos humanos en Colombia, https://news.un.org/es/story/2020/02/1470201 (6 March 2020).

UN (2017), The UN Mission Finalizes Activities of Neutralization of the FARC-EP Armament, https://unmc.unmissions.org/en/un-mission-finalizes-activities-neutralization-farc-ep-armament (10 February 2020).

UNODC (2019), Colombia. Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2018, Bogotá: UNODC-SIMCI.

Zambrano Quintero, Liliana (2019), La reincorporación colectiva de las FARC-EP: una apuesta estratégica en un entorno adverso, in: Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 121, 45–66, doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2019.121.1.45. .

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

García Pinzón, Viviana (2020), Colombia: Between the Dividends of Peace and the Shadow of Violence, GIGA Focus Latin America, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-66908-5

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.