- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The End of Apathy: The New Africa Policy under Joe Biden

GIGA Focus Africa

The End of Apathy: The New Africa Policy under Joe Biden

Number 2 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3603

The new US president has promised a fundamental change in American foreign policy after the Trump years: “America is back.” The start of Joe Biden’s presidency in January 2021 is therefore also associated with considerable expectations in sub-Saharan Africa. Four key issues will determine whether the new US administration will really deliver on these expectations.

Security policy priorities, especially the fight against spreading Islamist terror, shape US Africa policy. Some of the world region’s most authoritarian states are among the US’s closest partners in sub-Saharan Africa in this regard. President Biden has promised to make the international promotion of democracy a central priority in the future.

If the fight against climate change is really to become a hallmark of the Biden administration, this cannot happen without Africa being onboard. So far, however, the US has continued to support numerous large-scale projects in Africa that rely on fossil fuels.

US development cooperation with Africa focuses on fighting diseases such as HIV/AIDS. In light of COVID-19, greater focus on strengthening health systems, vaccination programmes, and overcoming the pandemic would help counterbalance China’s “vaccine diplomacy.”

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) supports African exports to the US. However, the effect has been limited and US–African trade has fallen far behind that between Africa and China.

Policy Implications

A fundamental shift in US Africa policy is not to be expected under President Biden. However, there are new opportunities for cooperation in health and overcoming the current COVID-19 pandemic, in climate policy, and in promoting democracy. Given the US focus on geostrategic competition with China, however, expectations should remain realistic.

United States “Africa Policy”: Biden Administration Makes Immediate Changes

The Biden administration has not wasted time in making drastic changes in United States Africa policy. As in other policy areas, a fundamental change of tone is afoot. While predecessor Donald Trump denigrated African nations as “shithole countries,” the Biden administration has promised “mutually respectful relations” and immediately rescinded a travel ban on citizens from numerous Muslim-majority nations on coming to power. This travel ban also affected African, especially West African, states.

We can expect that Biden’s foreign policy team, led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, will see Africa (in this GIGA Focus, “Africa” refers to sub-Saharan Africa) first and foremost for what it is. Namely, a dynamic and rapidly growing continent with an extremely young population who are expected to make up more than one-quarter of the world’s inhabitants by 2050. Moreover, the sheer number of states making up the continent as a whole (55) already signifies the considerable weight Africa carries both on the international stage and within the United Nations system.

At the same time, and as before, “Africa” is unlikely to become a core focus of the US administration. In his foreign policy principles “Why America Must Lead Again,” which Biden published in March 2020 in Foreign Affairs, the world region appears in only one sentence at all, a reference to the Ebola epidemic aside: “And we need to do more to integrate our friends in Latin America and Africa into the broader network of democracies and to seize opportunities for cooperation in those regions” (Biden 2020: 73). The dominant foreign policy focus in Washington remains on the geostrategic competition with China. This is by no means a new development: While Trump imposed punitive tariffs on goods from China, President Barack Obama spoke of the much-cited “pivot to Asia.” As vice president, Biden had been instrumental in shaping this focus at the time. Although the election of the first black US president in 2008 was euphorically celebrated in African countries, he largely ignored the continent. Ever since the presidency of Bill Clinton (1993–2001), in fact, a remarkable consensus has emerged between Democrats and Republicans on the basic tenets of US Africa policy. The rhetoric of the new US administration is therefore likely to change much more drastically than its actual Africa policy.

What foreign policy towards African states can we expect from the Biden administration then? And, what potential for cooperation is there for African partner countries – but also for Germany and the European Union? To this end, this analysis examines the development of US Africa policy since the turn of the new millennium and provides an outlook on potential developments in the policy fields of security, economics, development cooperation, and democracy.

The Focus on Counterterrorism

A major focus of US Africa policy to date has been counterterrorism and support for the military and special forces. It should not be forgotten that as early as 7 August 1998 bombs were detonated simultaneously in tankers outside the US embassies in Nairobi (Kenya) and Dar es Salaam (Tanzania). These African “9/11” terrorist attacks killed more than 220 people and left several thousand injured, while also completely destroying the embassy buildings. Even before the airplane attacks of 11 September 2001 these Islamist terrorist attacks led to a “securitisation” of US Africa policy that continues to determine the country’s relationship with the continent as a whole today.

Since 2001 at the latest, the US military has established a network of bases in 15 African countries – primarily in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. These serve first and foremost to combat jihadist terrorist groups, which are spreading in particular in the Sahel, Nigeria, Somalia, and also Mozambique, while also threatening those countries’ neighbouring states. The central military base on the entire continent is Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, East Africa.

The activities engaged in are extensive: over the years, Washington has paid billions of dollars in “security assistance” to African partner governments, while US special operations forces themselves conducted counterterrorism combat missions in at least 13 African states between 2013 and 2017. In 2019, the United States launched airstrikes against Al-Shabaab and Al-Qaeda terrorist targets in Somalia on average once per week (Turse 2020). “Military advisors” train African soldiers and conduct missions themselves: for example, against the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda. In 2007, during the presidency of George W. Bush (2001–2009), U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) was established in Stuttgart, Germany, to manage the deployments. As of January 2020, according to AFRICOM, 5,100 Army personnel and 1,000 Pentagon-employed civilians were stationed in Africa (Husted et al. 2021). Numerically at least, this presence contradicts the official narrative that US forces have only a “‘light’ footprint” on the African continent (Turse 2020).

So far, there are no signs that the Biden administration will become more involved militarily or in counterterrorism. At the same time, it is also unclear whether Trump’s decision to withdraw troops from Africa will be reversed.

Rapid Rise in Africa’s Economic Relations with China

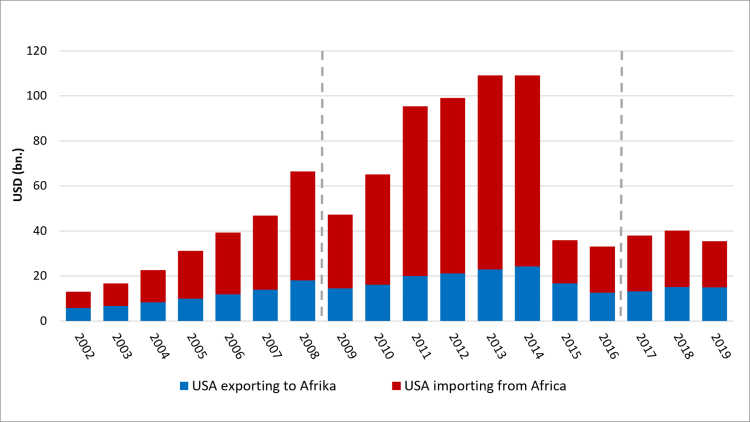

The US’s two largest trading partners in Africa Nigeria and South Africa together account for more than half of all US–Africa trade. Overall, trade with Africa represents only 1 percent of total US foreign trade, however. Traditionally, African countries export more goods to the US than vice versa (see Figure 1 below). While African countries primarily sell natural resources (crude oil already accounts for one-third of total exports), various processed items are imported from the US. This imbalance with the world’s poorest region on average is deliberately promoted by the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which has been in force for 20 years now. It allows duty-free imports of goods from numerous African nations and has primarily supported trade in African-produced clothing, the most important processed export to the US. AGOA is widely recognised in the region.

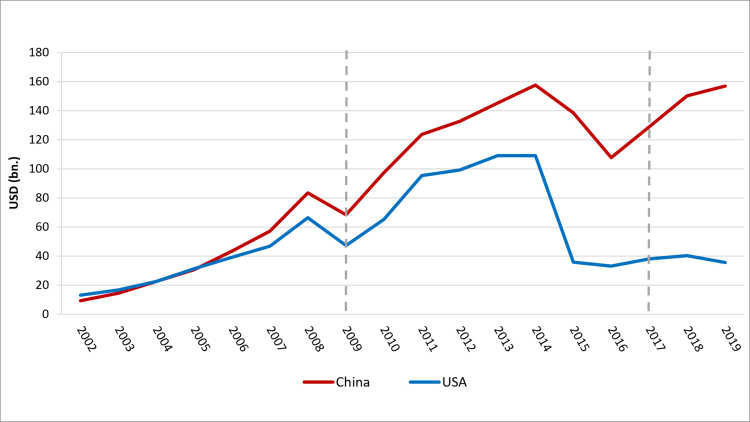

However, trade between African countries and the US has declined sharply over the past five years. At the same time, a comparison shows that China has become an increasingly important trading partner for sub-Saharan Africa and the whole continent as a whole. The effects hereof are serious: today, the volume of trade between African countries and the People’s Republic is almost four times as high as that with the US (see Figure 2 below).

Against this backdrop, the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act (BUILD Act) was passed in 2018; it had been initiated by the U.S. Congress and not the Trump administration. The BUILD Act doubles the default protection for US investments in infrastructure projects in developing countries up to a total of USD 60 billion. The Act can be understood as a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the accompanying massive financing and construction of major infrastructure projects in Africa. A prominent example of China’s billion-dollar investment is the 752 kilometres of new train track between Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa and the port in Djibouti. However, a consistent US strategy for strengthening economic relations with African states has not emerged from this initiative to date.

Stable Development Cooperation

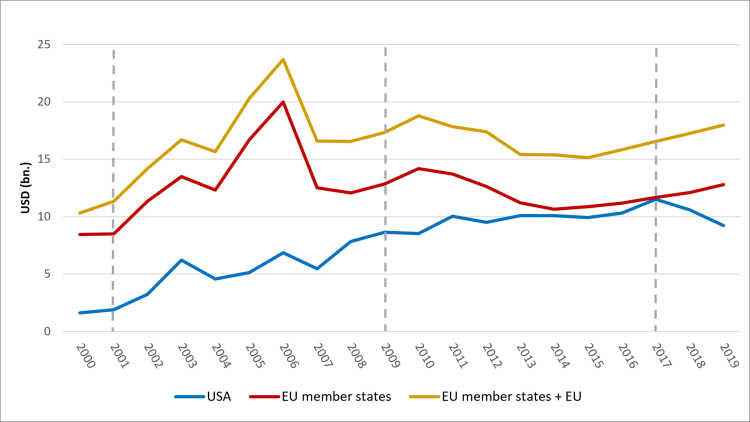

On several occasions, the Trump administration attempted to massively scale back US development assistance and humanitarian aid to African countries. This was in line with his administration’s repeated accusation that development aid is generally ineffective and prone to corruption. The previous president wanted to cut the budget of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) by almost one-third. However, the U.S. Congress prevented this, with votes coming from members of the Republican Party too, and kept funding for development aid programmes at high levels. US development assistance to sub-Saharan Africa was about USD 3 billion below EU funding in 2019 (see Figure 3). Moreover, the Trump administration continued almost all existing initiatives, launched new ones such as “Prosper Africa,” and even expanded USAID’s presence in countries such as Niger. Development policy under Trump thus remained contradictory and much more traditional than announced (and feared by some).

A particular focus of US development cooperation lies in the fight against disease, precisely the area from which the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) wanted to largely withdraw before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Over the past decade, nearly three-quarters of US aid to African nations has gone to fight disease and malnutrition, particularly HIV/AIDS, malaria, and childhood diseases (Husted et al. 2020). Of particular importance are the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched by George W. Bush in 2003, and the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), started two years later. Support for healthcare totalled USD 5.3 billion in the fiscal year 2019. In addition, the private Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is actively engaged in disease control with billions in funding. Even the US government Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), established in 2004 to support successful reform states, especially in Africa, has endured and is expected to have a USD 800 million budget in fiscal year 2021 (MCC 2020). However, the wide variety of Africa programmes and ministries, as well as institutions involved, have led to fragmentation, making a strategic US Africa policy immensely more difficult.

So far, the Biden administration has not indicated that it intends to devote more funds to development aid for African countries. Given the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic this seems unlikely. However, personnel decisions point to an upgrading of the dossier at least. Secretary of State Blinken, unlike US ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield, has previously had no particular professional contact with sub-Saharan Africa. The acting assistant secretary for the Bureau of African Affairs at the State Department, Robert F. Godec, is an accomplished diplomat with extensive experience in Africa (he was previously ambassador to Kenya, among other places), but not a political heavyweight. He stands for a structured, professional Africa policy. In contrast, the appointment of Samantha Power as head of USAID came as a surprise. She was the Obama administration’s UN ambassador from 2013 to 2017 and is one of the best-known voices for international human rights protection in the US. She is also slated to become a member of the White House National Security Council, a clear upgrading of this position; doing so would also establish a stronger link between development issues and security within the Biden administration.

In terms of content, the fight against climate change could become the hallmark of President Biden’s Africa policy. If the fight against climate change is indeed to become central to the Biden administration, it cannot be so without African states onboard. This applies both to working with African partners in UN climate change conferences and to supporting development models that do not rely on the gigantic resource consumption and CO2 emissions of industrialised countries and other rising states like China. An initiative to reduce fossil fuel-dependence in African countries could become President Biden’s signature African aid programme. Such a plan would also offer multiple entry points for cooperation with European partners.

Second, helping African countries overcome the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath will be critical in the time ahead. In this regard, the US can draw on its experience and strong commitment to fighting the Ebola epidemic in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia between 2013 and 2016. In addition, China’s “vaccine diplomacy,” particularly in Asia, demonstrates the enormous political potential that lies in such outside contribution. Global distributions of vaccines are highly unequal, to the detriment of world regions like sub-Saharan Africa. The US could engage more bilaterally, support the COVID-19 international vaccine alliance COVAX, and use its expertise – in addition to fighting individual diseases like HIV/AIDS – to invest even more in African public-health systems. This would massively increase the world region’s resilience to pandemics like COVID-19, and offer great opportunities for collaboration with the EU and Germany too.

Dare to Be More Democratic

Even under the Trump administration, promoting democracy, human rights, and good governance in African countries figured prominently in public pronouncements – for example, from National Security Adviser John Bolton (in office: 2018–2019). Indeed, in earlier years, MCC programmes with Madagascar and Mali were terminated because of unconstitutional changes of power. Moreover, election monitoring makes up an important part of the US approach. However, a disconnect has long been apparent between proclaimed goals and current cooperation with African states.

First, support for good governance and civil society accounts for only a small portion – between USD 250 million to USD 300 million – of USAID programmes each year. Moreover, reports suggest that the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor has too few staff to meaningfully carry out its 450 active programmes (Devermont 2019: 6). Second, despite announcements by various US administrations that they would end development cooperation with authoritarian states, countries with repressive governments such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia were among the top recipients of US development assistance in fiscal year 2021 (and before) (Husted et al. 2020: 14). However, this is true not only of the United States but also of numerous other Western governments, which also cooperate with strategically or otherwise “important” authoritarian states. Observers from Africa also criticise the US for supporting “Africa’s strongmen” (Tampa 2020). In any event, the widely used argument that authoritarian governments “get things done better” has feet of clay. Recent research clearly shows that democratic governments do more for their citizens, at least in the longer term: on average, they invest more in education and achieve higher growth rates (Harding and Stasavage 2014; Masaki and van de Walle 2014).

Promoting democracy internally and externally and cooperating with other democracies has been posited as a central pillar of Biden’s presidency. In his election campaign, he promised greater support for Africa’s democracies. He also announced that he would invite democracies to a “Summit of Democracies” as early as 2021. Those in sub-Saharan Africa such as Ghana, Senegal, and South Africa, as well as democratising states and civil society organisations, should also play a prominent role therein.

More consistent support for democracies in Africa would be a real paradigm shift in US policy (and in that of other states as well; for criticism of the EU, for example, see Brummer 2009). This area offers particular potential for increased cooperation with the new US administration. Pursuing this seems especially important in light of the fact that democracies in Africa have also come under pressure, that numerous African governments have used the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic to restrict democratic rights, and that China’s negative influence on democratic processes in African states still continues to grow. For example, the EU and US could pay much more attention to developing a coordinated approach in responding to electoral fraud and to the use of democracy sanctions in order to prevent “forum shopping” by respective governments.

Cooperation on the International Stage

Already two months after taking office, we see the Biden administration’s new presence on the international stage – which is also of significance for African states. President Biden is thus fulfilling key announcements that America wants to “lead” internationally again (Biden 2020). First, the United States supported the appointment of Nigeria’s former finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala as the first female director-general of the World Trade Organization. In addition, the US will resume payments to UN programmes; this will have a major impact in many African nations. The country also returned to the World Health Organization. Finally, serving as at least a symbolic gesture, Secretary of State Blinken announced his country’s intention to apply for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council. All of these actions point to a strengthening of multilateralism by the United States. However, the new administration’s failure to withdraw unilateral US sanctions against International Criminal Court prosecutors sends a different signal.

The true test of multilateral cooperation, however, will come in sub-Saharan Africa itself. The US will only succeed if it does not see its African engagement as (merely) part of a geostrategic agenda to push back against China’s growing global influence. What should not be overlooked in the focus on its geostrategic race with China is that the “rest” – including African states – continue to have considerable room for manoeuvre (Narlikar 2021). Although the United States lost significant prestige under the Trump administration, its soft power is still considerable. Recall the location of the world’s leading universities, which are also a major draw for African students. But here, too, China has caught up – the current number of African students in China is 20 times higher than 10 years ago.

Prospects for US Africa Policy

Although China now appears to be too far ahead as a key foreign trade partner of African countries, the People’s Republic may well increase the incentives for the US to engage more substantially in sub-Saharan Africa (and with the continent as a whole) – also to form a counterweight. To this end, the Biden administration could focus on its policy priorities and the US’s particular strengths: in health, in combating climate change, in strengthening the economy by facilitating market access and supporting the new African Continental Free Trade Area, in strengthening the African Peace and Security Architecture (including in tackling jihadist forces), in genuinely strengthening democratic forces, and in cooperation at the international level and at the UN. After all, the African continent as a whole accounts for more than one-quarter of the UN’s entire membership.

The big question remains how ambitious the Biden administration will in fact be in its Africa policy. Here, expectations should not be too high. On a sober note, Republican presidents have done more for African countries than Democrats over the past two decades (Trump aside). Sub-Saharan Africa enjoyed the most attention from the US under George W. Bush. However, even he did not remedy but actually increased a central weakness of the country’s Africa policy: namely, the “hopeless fragmentation of institutions and programs” and the “proliferation of uncoordinated development assistance programs for Africa,” as van de Walle (2009: 6) already lamented 12 years ago. Every US incumbent of the past 20 years launched their own “presidential initiative” for Africa (PEPFAR, Power Africa, Feed the Future, Prosper Africa). It would be a surprise if Biden did not follow suit and launch his own initiative, for example with regard to fighting climate change in African countries. That is honourable. Instead of another presidential initiative, however, a comprehensive and strategic approach to Africa would be ultimately desirable.

African analysts and policymakers, in light of these experiences, welcomed the election of Biden but have taken it much more soberly than that of Obama in 2008. Not only did predecessor Trump smash a lot of porcelain, the overall low strategic importance of sub-Saharan Africa for the US is obvious. Thus, Tampa (2020) asks, “Obama didn’t deliver for Africa—can Biden prove that black lives matter everywhere?” Adegoke (2020) also predicts that the Biden administration will follow the traditions of US Africa policy and expects “a different (more respectful) tone, but no major changes in policy.” Thus, a break with established US Africa policy is not in sight. Yet, the “American dream” in Africa is being challenged by the cooperation with and strong engagement of China.

So far, coordination with international partners – that with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund aside – has not been one of the strengths of US Africa policy. President Biden’s repeated commitment to multilateral cooperation and the international strengthening of democracy could open the door in Africa policy to increased cooperation with African states, the EU, and Germany alike. German foreign minister Heiko Maas is currently pursuing the goal of building an “alliance for multilateralism.” Why not, then, jointly support African initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area and the African Peace and Security Architecture, and work together to end armed conflicts such as in Ethiopia’s Tigray region?

Footnotes

References

Adegoke, Yinka (2020), How a Biden Administration Will Change US-Africa Relations, in: Quartz Africa, https://qz.com/africa/1929614/how-a-joe-biden-will-change-donald-trumps-us-africa-relations/ (1 February 2021).

Biden, Joseph R. (2020), Why America Must Lead Again, in: Foreign Affairs, March/April, www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again (29 January 2021).

Brummer, Klaus (2009), Imposing Sanctions: The Not so ‘Normative Power Europe’, in: European Foreign Affairs Review, 14, 2, 191–207.

China Africa Research Initiative (2021), China-Africa Annual Trade Data, Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, www.sais-cari.org/data-china-africa-trade (23 March 2021).

Devermont, Judd (2019), The Game Has Changed: Rethinking the U.S. Role in Supporting Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), www.csis.org/analysis/game-has-changed-rethinking-us-role-supporting-elections-sub-saharan-africa (17 February 2021).

Harding, Robin, and David Stasavage (2014), What Democracy Does (and Doesn’t Do) for Basic Services: School Fees, School Inputs, and African Elections, in: The Journal of Politics, 76, 1, 229–245.

Husted, Tomas F. et al. (2021), Sub-Saharan Africa: Key Issues and U.S. Engagement, Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Husted, Tomas F., Alexis Arieff, Lauren Ploch Blanchard, and Nicolas Cook (2020), U.S. Assistance to Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview, Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Masaki, Takaaki, and Nicolas van de Walle (2014), The Impact of Democracy on Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1982-2012, Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER).

MCC (Millennium Challenge Corporation) (2020), Congressional Budget Justification, FY 2021, Washington, DC: MCC, www.mcc.gov/resources/doc/cbj-fy2021 (17 February 2021).

Narlikar, Amrita (2021), Must the Weak Suffer What They Must? The Global South in a World of Weaponized Interdependence, in: Daniel W. Drezner, Henry Farrell, and Abraham L. Newman (eds), The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence, Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 289–304.

OECD Data (2021), Aid (ODA) Disbursements to Countries and Regions [DAC2a], OECD Stat., https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=Table2A# (23 March 2021).

Tampa, Vava (2020), Obama Didn’t Deliver for Africa – Can Biden Prove That Black Lives Matter Everywhere?, in: The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/nov/30/obama-didnt-deliver-for-africa-can-biden-show-black-lives-matter-everywhere (5 January 2021).

Turse, Nick (2020), Pentagon’s Own Map of U.S. Bases in Africa Contradicts Its Claim of ‘Light’ Footprint, in: The Intercept, https://theintercept.com/2020/02/27/africa-us-military-bases-africom/ (17 February 2021).

van de Walle, Nicolas (2009), US-Afrikapolitik: Bushs Vermächtnis und die Regierung Obama, GIGA Focus Afrika, 5, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/11578901-us-afrikapolitik-bushs-vermächtnis-regierung-obama/ (22 March 2021).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Africa

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Africa

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

von Soest, Christian (2021), The End of Apathy: The New Africa Policy under Joe Biden, GIGA Focus Africa, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-72204-9

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.