- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Latin America – Multilateralism without Multilateral Values

GIGA Focus Latin America

Latin America – Multilateralism without Multilateral Values

Number 7 | 2019 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Latin America and the Caribbean are considered natural allies for German foreign policy efforts to strengthen liberal multilateralism. However, an analysis of cooperation in the region presents an ambiguous picture. Particularly with respect to core elements in the liberal canon of values such as democracy and human rights, Latin American governments primarily pursue their own political interests.

The most successful element of Latin American multilateralism is the intergovernmental settlement of disputes, which has been institutionalised since 1948 in the Pact of Bogotá. In acute crises, however, ad hoc institutions take the place of established multilateral mechanisms. Ideological proximity is more important than values and norms.

The core elements of liberal multilateralism are democracy and human rights. The Latin American countries have not only signed the most international agreements on these values but have also anchored them in the inter-American system. In practice, however, implementation has proven to be difficult.

The crisis in Venezuela demonstrates the ambiguous nature of multilateral cooperation at the interface between regional stability and countries’ own political interests. The Organization of American States (OAS) condemned the increasing authoritarianism early on, but has failed at implementing sanctions due to polarisation along ideological and party lines. The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) disintegrated as a result of the crisis.

Policy Implications

Reliable partnerships within the multilateral system, in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as elsewhere, are contingent on the protection and implementation of democracy and human rights in the partner countries themselves. Lip-service commitments are not enough. This should be at the forefront of German and European foreign policy. Only when the domestic and foreign policy standards are in harmony can stable partnerships emerge.

Germany Seeks Partners

With the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote, the crisis facing liberal multilateralism reached the heart of German foreign policy. In his search for multilateral cooperation partners, federal foreign minister Heiko Maas invited his colleagues from Latin America and the Caribbean to a conference in Berlin in 2019. The region’s countries were said to be “natural allies” in strengthening multilateralism which agreed with Germany “that democracy, the rule of law, and fair and free trade are the only way” (Federal Foreign Office 2019).

The reference to the shared community of values and interests between Germany or the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean is nothing new, but has rather been a recurring mantra since the end of the Cold War and the democratisation of Latin America (Federal Foreign Office 2010). However, nationalist governments with little interest in liberal cooperation (Flemes 2018) have increasingly been asserting themselves across the continent, and not just since the election of Jair Bolsonaro at the end of 2018. Simultaneously, fundamental structural problems are currently erupting throughout the entire region, showing how fragile the supposed consensus in the areas of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law is. An analysis of multilateral cooperation on these topics in and with the region therefore presents a rather ambiguous picture. Multilateral cooperation in and with Latin America has been successful in the area of classical security policy intended to prevent violent interstate conflicts. When it comes to the core elements of the liberal canon of values, which are more closely linked to domestic developments, governments either cite the principle of national sovereignty or pursue their own political interests. The crisis in dealing with Venezuela in recent years shows very clearly the challenges and ambiguities of multilateral cooperation in and with Latin America.

A Zone of Peace – in Interstate Relations

In January 2014, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) declared Latin America and the Caribbean a “zone of peace.” The heads of state stressed respect for international law, the peaceful settlement of disputes, non-interference in internal affairs, the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, and the promotion of a culture of peace.

The region has indeed enjoyed a long history of regional cooperation since its independence 200 years ago. In 1826 the Panamanian Congress established a system of cooperation between the former Iberian colonies, which the USA also became part of with the First International Conference of American States in 1889. At the Ninth Inter-American Conference of American States in 1948, the states founded the Organization of American States (OAS) as a regional organisation within the framework of the United Nations system. The Pact of Bogotá outlines comprehensive mechanisms for peaceful conflict resolution and is intended to prevent the use of violence and to regulate when a case is brought before the International Court of Justice or the UN Security Council.

For a long time the pact was replaced by ad hoc mechanisms established specifically for particular conflicts. One example is the Contadora Group, which was founded in the mid-1980s to avoid the escalation of internationalised civil wars in Central America into a regional war. The OAS was paralysed due to the existing ideological polarisation. The governments of the neighbouring states Mexico, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela mediated and laid the foundation for the Esquipulas regional peace agreement. Other bilateral conflicts – for example, between Argentina and Chile – were also defused through the mediation of various actors (Flemes and Radseck 2009). In recent years the International Court of Justice has made a number of arbitration rulings on old border disputes. The governments of Chile and Peru adopted the ruling on the delimitation of the maritime boundary in 2014 (Wehner 2014); Colombia’s government, in contrast, left the Pact of Bogotá following a ruling on its Caribbean maritime boundary that benefited Nicaragua (Urueña 2013).

Overall, multilateral cooperation to de-escalate and resolve interstate conflicts is considered to have been largely successful. This may also be because the Latin American states have very similar structures historically and culturally speaking, and because control of the border regions has always only been of interest when it has involved the control and exploitation of valuable natural resources. Whether the relatively peaceful interstate interactions are linked to the existing conflict management mechanisms or rather to a low-level of conflict in interstate relations or a peace-inducing dominance on the part of the USA (Pax Americana) remains the subject of debate (Kacowicz and Mares 2016; Mares 2012).

Protecting Democracy

In order to protect and implement core liberal values – democracy, human rights, accountability – Latin America has signed comprehensive treaties, particularly in the context of the OAS. Latin American countries were a central element of the third wave of democratisation that began in the mid-1970s in Southern Europe with Portugal, Spain, and Greece. Mainwaring and Bizzarro (2019) identify 91 cases of democratisation up to the year 2017, including 18 in Latin America and the Caribbean. In contrast to other regions, only four cases of collapse can be identified here (Dominican Republic, 1990; Peru, 1992; Nicaragua, 2008; and Honduras, 2010). The authors observe an erosion of democratic progress in Ecuador and stagnation in Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic (following renewed democratisation in 1996), and Panama. The remaining eight countries (Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay), on the other hand, are making progress, albeit based on very low initial values. Latin America has therefore been far more successful than other regions. Venezuela is not included in this analysis as it was already democratic before the third wave of democratisation.

On 11 September 2001, the 34 OAS member states signed the Inter-American Democratic Charter at a special session in Lima, Peru (OAS 2001). In 1985, the OAS had adopted a protocol that declared democracy to be essential to “stability, peace, and development.” Now people’s right to democracy and governments’ obligation to promote and defend it were enshrined in the charter. The charter explicitly refers to representative democracy, and Article 3 states that the central components are respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms; access to and exercise of power on the basis of the rule of law; the holding of regular, free, and fair elections with secret ballots and universal suffrage; a pluralist system of political parties and organisations; and the separation of powers.

The charter has since been applied in relation to two countries. The first time was in 2002, when an attempted coup against Hugo Chávez took place, though he was already back in power after three days, which meant that the OAS could not take any action. However, the recognition of the “transitional government” by the US government under George W. Bush shows that old friend–enemy patterns remained predominant. Starting in 2016, OAS general secretary Luis Almagro made several attempts to sanction the increasing authoritarianism of the Maduro government. For a long time, these efforts failed due to the support Maduro received from Nicaragua, Bolivia, and numerous other Caribbean states that received preferential conditions for oil imports under Petrocaribe. When a majority in favour of the implementation of sanctions was finally achieved, the Venezuelan government declared its withdrawal from the OAS, which was to take effect in May 2019.

The sanction mechanisms were applied for a second time following the coup against Honduran president Manuel Zelaya in 2009. The OAS’s preventive efforts to defuse the domestic crisis failed, and on 28 June 2009 soldiers pulled the president out of bed in the middle of the night and put him on a plane to Costa Rica. The OAS reacted immediately with the strongest sanction and suspended Honduras’s membership. This had no consequences, however, because the transitional government played for time and the USA quickly broke ranks with the front rejecting the coup. The OAS was once again deeply divided in its evaluation of the subsequent elections in November 2009, and in 2011 Honduras was admitted again (Legler 2012).

Ultimately, four factors influence the application of existing regional mechanisms to protect democracy (Feldmann, Merke and Stuenkel 2019): First, the fact that there are competing rules and regulations. Using sanctions in response to violations goes against the rejection of interventions in other states’ domestic affairs, which has strong roots in Latin American history. Ribeiro Hoffmann (2019) also correctly points out that there are strong differences in the region between the advocates of representative and participatory democracy regarding the central cornerstones of democracy. Second, the mechanisms lack suitable leverage that would actually force the governments involved to give in. Third, the USA’s ongoing and considerable influence continues to be viewed critically. Its support for the coup against Chávez in 2002 and its about-face in favour of the transitional government in Honduras were seen as yet more signs that the priority is not the enforcement of liberal norms and values, but that these are instead a pretext for securing US economic and strategic interests. Finally, the heavily consensus-oriented mechanisms impede robust and concrete action.

The Implementation of Fundamental Human Rights

A second element of liberal multilateralism is the protection and implementation of fundamental human rights, an area in which Latin America has taken on a pioneering role. Nine months before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was proclaimed on 10 December 1948 and shortly before the official founding of the OAS at the Ninth Inter-American Conference of American States in Bogotá, the organisation adopted the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man. Latin America’s pioneering role in the codification of human rights has only recently received increased attention and recognition (Sikkink 2014). However, the focus on human rights issues in the region has always been overshadowed by a lack of implementation and serious human rights violations. An initial phase of democratisation in the 1940s and 1950s was followed by decades of military dictatorships and internal wars. Even though the wars have mostly ended and the region remains in large part formally democratic, it is still the most violent region in international comparison (UNODC 2019).

The Inter-American human rights system is based on the American Convention on Human Rights, which was adopted in 1969 and entered into force in 1978. In 1959 the states founded the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the central responsibility of which was to produce regular reports on the human rights situation in the member states and to advise the participating states on human rights issues. A third element is the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which was founded in 1979 as an organ of the convention and not of the OAS. Here both individuals and states can take legal action against human rights violations (Medina 1990).

Although these instruments have been unable to prevent the violation of fundamental human rights, they play an important role in working through and documenting these violations. With democratisation and the ending of the internal wars, Latin America has also contributed significantly to the development of innovative human rights instruments. Examples include the truth commissions in Argentina and Guatemala and, currently, Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace.

With respect to both democracy and human rights, Latin America’s central problem is not a lack of rules or institutions. The lack of implementation can instead be explained by the fact that the political, economic and military elite have prevented or undermined the application of these rules. This is true above all for the rule of law, which must enforce adherence to democratic rules and the observation of fundamental human rights at the national level. The implementation of the regional rules and regulations has failed primarily due to widespread impunity – even in the case of capital crimes – and due to corruption, not only but also within the judicial system.

The example of Venezuela demonstrates how the lack of consensus regarding the core elements of democracy and human rights has impeded a regional response to the crisis.

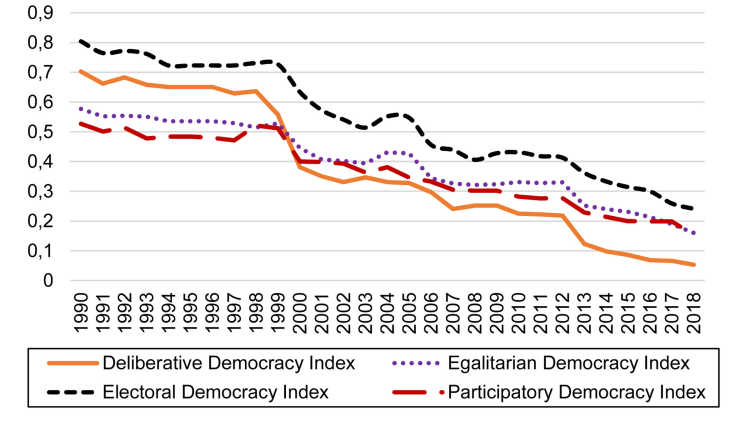

The Failure of Latin American Cooperation in Venezuela

When Hugo Chávez was elected Venezuelan president in 1998, the differences with regard to democracy and human rights, as well as regional cooperation, became evident. From the beginning Chávez propagated a model of democracy that foregrounded participation and privileged social human rights over political human rights. In practice, however, this led to the erosion of democratic institutions and the abolition of the separation of powers. While Chávez won the bulk of the generally mostly free elections with a large majority, his successor Nicolás Maduro (in power since 2013) faced growing criticism because of increasingly authoritarian tendencies, not only from the national opposition but also from regional organisations. Particular milestones in the direction of an authoritarian system were the manipulation of the electoral system and the militarisation of the state apparatus (Jácome 2018; Legler and Nolte 2019). However, data from the Varieties of Democracy project (Coppedge et al. 2019) shows that there has been a massive decline in all four dimensions of democracy (Figure 1).

In the case of Venezuela, the OAS attempted relatively early on to stop the further deterioration of core elements of democracy. When the opposition received an overwhelming majority in the 2015 National Assembly elections, it appeared that a turning point might be possible. However, the Maduro government did not give in: it did not recognise the victory of two opposition MPs, which meant the opposition did not have the two-thirds majority in parliament that would have allowed it to block all of the government’s initiatives. Maduro undermined the opposition’s attempt to remove him from office legally via an impeachment referendum (permitted during the first two years in office) – a measure introduced in 2004 via OAS mediation – by refusing to recognise the signatures that had been collected. The ultimate turning point was Maduro’s convening of a constituent assembly in 2017 to take over the parliament’s tasks.

The OAS tried to invoke the relevant articles within the Democratic Charter, but this failed due to the polarisation within the organisation. In April 2017, the Maduro government finally withdrew from the OAS. In response, 12 mostly conservative governments founded the Lima Group, in keeping with the tradition of ad hoc groups to deal with regional conflict management. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Peru, and Mexico – as well as Costa Rica and Canada – took part. Uruguay, Bolivia, and Nicaragua, on the other hand, did not join the initiative. While Uruguay tried to position itself as a neutral mediator, Bolivia and Nicaragua sided openly with the Maduro government.

The year 2017 was when the Maduro government used massive repression against opposition protesters who had taken to the streets. The protests were no longer gaining ground “only” within the traditional parties, but also among the population that had supported and elected Chávez. According to figures from the Observatorio de la Violencia (Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia 2019), 5,535 people died resisting the state security forces in 2017 and 7,523 in 2018. Mediation efforts in the Dominican Republic on the part of the former Spanish prime minister Zapatero and the Vatican failed because Maduro was unwilling to make any concessions and primarily tried to gain time. His rapidly sinking popularity was likely one of the main reasons that he moved the elections set for the end of 2018 up to May. A large segment of the opposition boycotted the elections and refused to recognise Maduro when his term ended on 10 January 2019. In this situation, the president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaido, declared himself interim president and demanded “the end of the usurpation and new elections” in the context of renewed mass protests.

Latin America remained divided. The USA and most of Latin America’s conservative governments, as well as Canada and most of the EU, recognised Guaido’s claim to the presidency. This recognition was associated with the hope that rapid regime change was possible, either through the implosion of the regime or the military changing sides. The threat of military intervention under US leadership was also made. The fact that numerous Latin American governments openly discussed this option, above all Colombia and Chile, represented a rhetorical break with the previously emphasised ban on intervening in the domestic affairs of other states. In these tense circumstances, some European and Latin American governments then founded the International Contact Group, which advocated for a negotiated solution – so far without success.

Latin America’s handling of the Venezuela crisis aligns seamlessly with the problems of multilateral cooperation in the region:

Cooperation to defuse acute interstate crises does take place, but it generally relies on newly founded ad hoc mechanisms rather than existing institutions.

With respect to democracy, different conceptions that depend on the ideological or political leanings of the particular government collide. Aside from the holding of elections, there is no minimum consensus in the region as to which core elements are indispensable. And elections also take place in authoritarian contexts.

When governments use force against their own populations, this still – even in the twenty-first century – falls largely under the rule of non-intervention, or it is criticised if the repressive government belongs to the “other” political camp. Here the logic of the Cold War, which fuels well-known notions of the enemy in Latin America using Cuba and Chavism, has survived.

Latin America – A Difficult Partner

The region’s handling of the Venezuela crisis shows that the optimistic assumption that new regional organisations such as UNASUR represented a qualitative leap in regional cooperation was premature. Current developments tend to support the sceptics, who point out that regional cooperation is primarily based on presidential cooperation and continues to involve traditional forms of working together (Legler 2013).

The crisis in and surrounding Venezuela, as well as other conflicts, demonstrate the highly ambivalent relationship of many governments to national and international regulations. Instead of pacta sund servanda (contracts must be honoured), the colonial motto se obedece pero no se cumpla (rules are formally respected but not actually implemented) applies. Against this backdrop, Latin America represents a rather difficult partner for reliable multilateral cooperation.

However, this relatively ambivalent relationship to international rules and contracts is not limited to Latin America. Rather than ideological orientation, it is the protection of basic liberal values such as democracy and human rights that is a good indicator in support of partnership on values and norms. This correlation should guide European and German foreign policy much more strongly than geostrategic and economic interests. Only when the standards for domestic and foreign policy are at least somewhat in harmony can stable partnerships emerge.

Footnotes

References

Coppedge, Michael et al. (2019), V-Dem [Venezuela 1990-2018] Dataset v9, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemcy19.

Federal Foreign Office (2019), Gemeinsam für Multilateralismus und Frauenrechte! [Together for Multilateralism and Women’s Rights!], www.auswaertiges-amt.de/de/aussenpolitik/regionaleschwerpunkte/lateinamerika/maas-lak-frauenmultilateralismus/2193808 (27 November 2019).

Federal Foreign Office (2010), Deutschland, Lateinamerika und die Karibik: Konzept der Bundesregierung [Germany, Latin America and the Caribbean: The Federal Government’s Concept], www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/213420/e134842d489660405b58c361489b78e7/lak-konzept-dt-data.pdf (27 November 2019).

Feldmann, Andreas E., Federico Merke, and Oliver Stuenkel (2019), Argentina, Brazil and Chile and Democracy Defence in Latin America: Principled Calculation, in: International Affairs, 95, 2, 447–467, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz025.

Flemes, Daniel (2018), Brazil’s Elections: Nationalist Populism on the Rise, GIGA Focus Latin America, 5, September, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/brazil’s-elections-nationalist-populism-on-the-rise (27 November 2019).

Flemes, Daniel, and Michael Radseck (2009), Creating Multilevel Security Governance in South America, GIGA Working Paper 117, www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publication/creating-multilevel-security-governance-in-south-america (27 November 2019).

Jácome, Francine (2018), Los Militares En La Política y La Economía de Venezuela Nueva Sociedad, in: Nueva Sociedad, 274, March–April, 119–128.

Kacowicz, Arie M., and David R. Mares (2016), Security Studies and Security in Latin America. The First 200 Years, in: Routledge Handbook of Latin American Security, Abingdon, New York: Routledge, 11–29.

Legler, Thomas (2013), Post-Hegemonic Regionalism and Sovereignty in Latin America: Optimists, Skeptics, and an Emerging Research Agenda, in: Contexto Internacional, 35, 2, 325–352, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-85292013000200001.

Legler, Thomas (2012), The Democratic Charter in Action: Reflections on the Honduran Crisis 1: The Democratic Charter in Action, in: Latin American Policy, 3, 1, 74–87, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-7373.2012.00057.x.

Legler, Thomas, and Detlef Nolte (2019), Venezuela: la protección regional multilateral de la democracia, in: Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica, 19, 2, 43–51.

Mainwaring, Scott, and Fernando Bizzarro (2019), The Fates Of Third-Wave Democracies, in: Journal of Democracy, 30, 1, 99–113, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0008.

Mares, David (2012), Latin America and the Illusion of Peace, London: Adelphi Papers.

Medina, Cecilia (1990), The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Reflections on a Joint Venture, in: Human Rights Quarterly, 12, 439–464.

OAS (2001), Inter-American Democratic Charter, 11 September, www.oas.org/charter/docs/resolution1_en_p4.htm (10 December 2019).

Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia (2019), Informes, https://observatoriodeviolencia.org.ve/category/informes/# (10 December 2019).

Ribeiro Hoffmann, Andrea (2019), Negotiating Normative Premises in Democracy Promotion: Venezuela and the Inter-American Democratic Charter, in: Democratization, 26, 5, 815–831, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1576033.

Sikkink, Kathryn (2014), Latin American Countries as Norm Protagonists of the Idea of International Human Rights, in: Global Governance, 20, 3, 389–404.

UNODC (2019), Global Study on Homicide, Wien: UNIS.

Urueña, Rene (2013), Colombia se retira del Pacto de Bogotá: Causas y Efectos, in: Universidad Diego Portales (eds), Anuario de Derecho Público, 511–547.

Wehner, Leslie (2014), Internationale Rechtsprechung in Grenzkonflikten: der Fall Chile – Peru, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, February, www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publication/internationale-rechtsprechung-in-grenzkonflikten-der-fallchile-–-peru (27 November 2019).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Kurtenbach, Sabine (2019), Latin America – Multilateralism without Multilateral Values, GIGA Focus Latin America, 7, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-65887-1

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.