- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Social Media in Morocco: From Grassroots Activism to Electoral Campaigns

GIGA Focus Middle East

Social Media in Morocco: From Grassroots Activism to Electoral Campaigns

Number 4 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3611

The Moroccan elections of September 2021 were unusual for various reasons. As electoral campaigning took place under pandemic circumstances, social media played a role previously unseen and contributed significantly to the unexpected victory of the National Rally of Independents (RNI), a liberal party, against the Justice and Development Party (PJD), an Islamist party.

The use of social media for campaigning purposes is not a completely new phenomenon in Morocco, given its prominent use by numerous social movements in the past. However, social media became a game-changer during the last elections.

Considering the COVID-19 measures imposed, political parties shifted much of their campaigning online. Today, online spaces are no longer exclusively used by grassroots activists but have become increasingly popular among Moroccan political parties.

While political parties converged in resorting to online spaces to compensate for the restrictions on offline campaigns, they diverged in their approaches; additionally, not all parties have the same financial capacity to exploit the full potential of social media. The huge disproportion in resources invested in online platforms was a main contributor to the victory of the RNI and the unexpected electoral wipeout of the PJD.

Policy Implications

To ensure equal opportunities for all involved political actors, a more effective legal framework is needed to guarantee the transparency and fair funding of digital electoral campaigns. This can be achieved by strengthening those institutions already in place and developing new ways to monitor the use of online media during elections.

The Elections of 2021 in the Context of COVID-19

The elections for Morocco’s House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwab/Assemblée des Répresentants) of September 2021 were unique in several interrelated respects. Electoral campaigning took place under the constraints established by the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media therefore played a role previously unknown in Morocco and contributed significantly to the unexpected victory of the National Rally of Independents (Rassemblement National des Indépendants, RNI), a liberal party, against the Justice and Development Party (Parti de la Justice et du Développement, PJD), an Islamist party. This is a novel development for Morocco, whose background must be elucidated in order to better understand the connections between future political dynamics and the use of social media in this important country in North Africa.

Parliament and Political Parties in Morocco

The task of the Moroccan House of Representatives is less to set the political agenda and more to implement and execute broader policy visions. It is comprised of 395 representatives belonging to numerous parties with different political orientations from post-independence, Islamic, and socialist backgrounds. Officially defined as a constitutional monarchy, the Kingdom of Morocco places much of its political agenda in the hands of the royal palace. King Mohammed VI appoints key heads of various ministries, including Interior, Religious Affairs, Foreign Affairs, and National Defence. Nonetheless, elections are held regularly, even though the result affects only a segment of the agenda-setting institutions. Citizens are generally aware of this limited room to manoeuvre by elected parties and, therefore, often refrain from voting. According to the official elections website (Al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya 2021), the average participation rate in the elections between 2007 and 2016 was around 41 per cent. Voter turnout has been further negatively affected by the pandemic and by bureaucratic obstacles to voting registration, especially as it concerns the Moroccan diaspora. To increase overall turnout, municipal, regional, and legislative elections in 2021 were combined and scheduled to take place on the same day, which led to an increase in voter participation to over 50 per cent (Al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya 2021).

Rising and Falling Political Trajectories

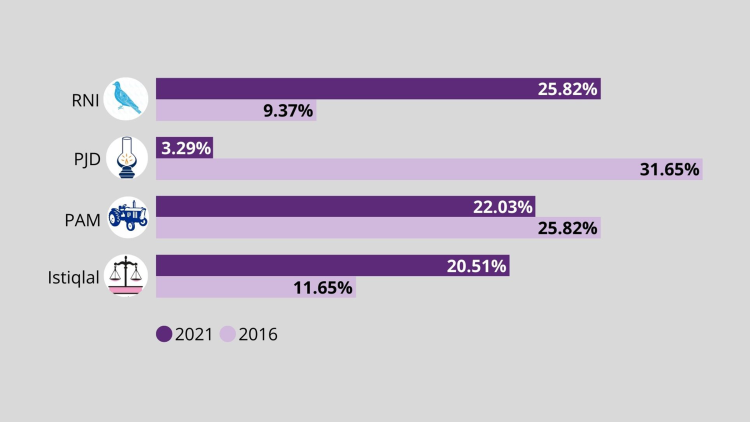

Several parties, such as the royalist Authenticity and Modernity Party (Parti Authenticité et Modernité, PAM), the nationalist Independence Party (Istiqlal), the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (Union Socialiste des Forces Populaires, USFP), and the Popular Movement (Mouvement Populaire, MP), actively competed in the elections of September 2021. But, given their leading positions during previous governments, the liberal RNI and the Islamist PJD were the main protagonists of this electoral contest. From its roots as part of the long-standing political opposition, the PJD developed into an Islamist party that not only recognised the superiority of the royal palace but also accepted the Moroccan electoral rules, eventually winning parliamentary elections in 2011 (with 22 per cent of the votes) and in 2016 (with 31 per cent of the votes). In the recent election, the PJD lost almost half of its previous candidates, who decided not to stand in these elections, probably because they felt disappointed by the party’s years in government, while almost all other parties augmented their candidate numbers. Different explanations exist for this PJD defeat. Among them are the internal differences between the former prime minister, Saadeddine Othmani, and the current general secretary, Abdelilah Benkirane, which shook the leadership of the Islamist party in 2016. Additionally, general dissatisfaction with the crisis management of the PJD government during the pandemic played a role. This included no or last-minute communication about drastic measures, such as the closing of internal and national borders. Further, the failure to fulfil earlier promises and meet the expectations of the previous electoral campaigns such as the rise in the retirement age, the reversal of wage cuts, and the abolition of teachers’ temporary employment contracts contributed to the waning trust in the party. In this respect, decisions made under pressure from the king, such as the normalisation of relations with Israel in 2020, further led to a distancing from the party’s ideals on the part of party members and voters alike.

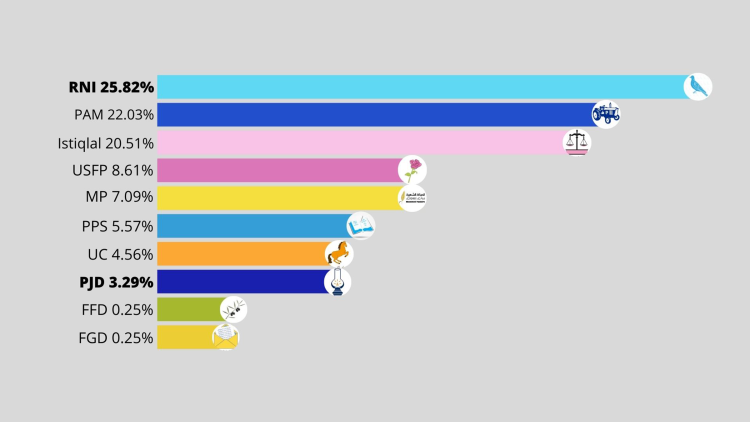

Figure 1. Results of the Elections for the Moroccan House of Representatives, September 2021

Source: Al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya 2021.

Note: PPS = Party of Progress and Socialism (Parti du Progrès et du Socialisme); UC = Constitutional Union (Union Constitutionnelle); FFD = Front of Democratic Forces (Front des Forces Démocratiques) ; FGD = Alliance of the Left Federation (Alliance de la Fédération de Gauche).

The RNI, on the other side, turned out to be the big winner of the 2021 parliamentary elections by almost tripling its votes since the previous elections five years earlier. This party is composed of elites, executives from the business sector, and high-profile representatives of the state. The RNI cannot be dissociated from its leader, Aziz Akhannouch, who is the co-founder of the fuel distribution company Afriquia and the second-richest man in the country after King Mohamed VI – and even a personal friend of the king. Akhannouch is not a new political actor: he played a crucial role in the formation of the second PJD government in 2017 as Minister of Agriculture and newly elected head of the RNI (as of 2016).

Figure 2. A Comparison of Election Results between 2016 and 2021

Source: Al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya 2021: visualisation by Eleonora Landucci.

Social Media before the Elections

To understand the changing role of social media within Morocco’s political landscape, we first need to take a look back. The government in power until September 2021 was formed by the PJD – a conservative-Islamist party that acknowledges the Moroccan monarchy and commits itself to democratic procedures and which was led by Saadeddine Othmani. During his government, several nationwide protest movements emerged in which social media was directly or indirectly involved. In 2016 the Hirak Rif Movement spread throughout the country following a viral video showing a fishmonger being crushed to death in a garbage truck after trying to save his allegedly illegal fish merchandise. Two years later, responding to the increasing prices, unemployment, and corruption, the online boycott of three big consumer brands (Danone, Sidi Ali, and Afriquia) led to political actors reconsidering the role of cyberactivism in Morocco. Social media coverage of these events not only helped to spread the activities of these movements and to polarise the public debate by triggering the direct intervention of the royal palace, but also contributed to diffusing a message already widespread during the Moroccan spring of 2011: that the government is incapable of responding to the population’s demands and that the king is the only stable political interlocutor (Mekouar 2018). Considering how useful social media has proven in mobilising for protests and boycotts during the last couple of years, it is no surprise that a leaked draft bill (decree 20.22) on social media regulation caused much outcry among Morocco’s civil society in spring 2020. The proposed bill on the criminalisation of consumer boycotts with penalties of up to a year in prison and a fine of up to the equivalent of USD 5,000 stirred anger and was perceived as a threat to the right of freedom of speech. This resulted in a large mobilisation and petition against the bill. With 75 per cent of the population having access to the internet, social media continued to play a significant role in social and political activism in Morocco, especially among the urban youth. The role of social media became even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic when offline protests were almost impossible. The general elections of September 2021 are a prime example of this.

In the pandemic context, the nature of political campaigning had to change because of the measures implemented by the Ministry of Interior. Restricted mobility, quarantine rules, and the discussion of possible election delays impacted the campaigns of all political parties. Moreover, the pandemic situation precluded political rallies and larger gatherings, as the group size for street protests was restricted to 25 people. Yet, in comparison to other contexts in the world, these restrictions can be seen as relatively mild. The lifting of several measures coincided with the abridged two-week election campaigns (the campaign started on 26 August and voting day was 9 September). In addition to that, the remaining measures were often circumvented. Consequently, campaigns on the ground remained a crucial tool, especially in terms of outreach to those in rural regions with less internet access. The possibility of having in-person campaign events was especially relevant for parties such as the PJD that had a great number of local supporters widely mobilised, particularly in larger municipalities.

The Changing Use of Social Media during Electoral Campaigns

As electoral campaigns are communicative events whose aim is to reach, inform, and persuade as many voters as possible, the use of media is at the very heart of any electoral campaign. Traditionally, Moroccan political parties used to depend on the combination of established media and face-to-face encounters in their electoral campaigns. This has changed over the last decade as many political actors started to use social media, especially since the Arab uprisings. Online communication was fostered especially in the last elections and, given the pandemic circumstances, political parties went the extra mile in using social media platforms to reach out to constituencies. In this regard, the strategic use of these platforms plays a significant role in increasing one’s visibility, enhancing self-image, and maximising chances of success to gain office. This resulted in the emergence of “digital campaigning,” the use of various social media platforms, such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram in the campaigning process, as a relatively new formal media practice in the context of Moroccan politics – particularly vis-à-vis elections. The question that arises is how these digital campaigns contributed to the victory of the RNI over the PJD.

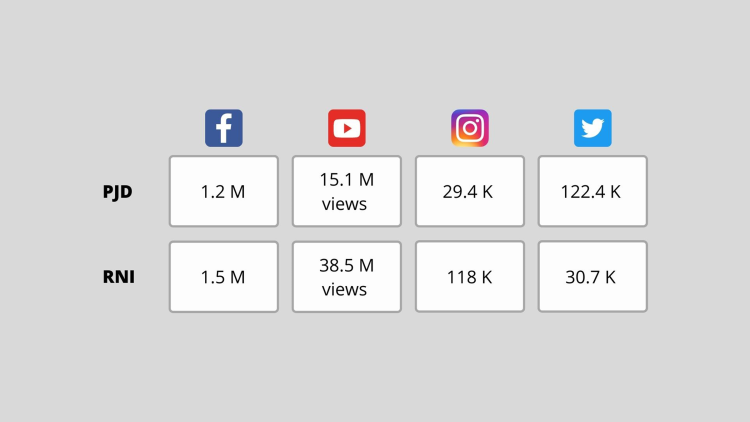

While all political parties converged in their recourse to online spheres, they clearly diverged in how they used social media in their electoral campaigns. While most of the parties’ online campaigns used ordinary tools such as pictures, posts, or live streaming videos that tend to be similar to or even the same as the established materials used by Moroccan parties (e.g. flyers, face-to-face interaction, speeches), they also worked on their communicative strategies and enhanced their online visibility, particularly as the elections approached. Overall, the RNI’s campaign was more effective and creative than those of other parties. Aziz Akhannouch was the most visible political candidate on various social media platforms before and during the elections. This success was the outcome of a range of interrelated factors: the RNI’s digital campaign was run by professionals, such as the British consultant Richard Bailey, whose strategy included hiring young people, combining online and offline tools, and producing various materials for different social media platforms. As shown in Figure 2, except on Twitter, the RNI outnumbered the PJD in terms of followers and traffic across the three other popular social media platforms in Morocco, namely Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram.

Figure 3. The Presence of PJD and RNI on Social Media Platforms

Source: Channels and accounts on the respective social media outlet (accessed 27 January 2022): visualisation by Eleonora Landucci.

Zooming in on the parties’ official YouTube channels, there is a clear disparity in their online content in terms of the number of videos, their structure, and their themes. Apart from the fact that the RNI’s content outsizes the PJD’s, the former is also better organised, more inclusive, and more up to date. For instance, unlike the visual presentation of the PJD’s YouTube playlist, the RNI’s choice of a vertical format not only gives the impression that the number of videos is much bigger but also allows various thematic playlists to be viewed at once. Furthermore, these playlists are organised into folders that vary according to target, length, and topic: some playlists focus on distinct subjects (e.g. achievements, upcoming projects), while others target specific groups (e.g. women, youth, people with disabilities, artists, Moroccans living abroad). The RNI’s playlists are also labelled with catchy titles such as “We promised and we kept our promise,” “A story and a commitment,” and “What I want for my city.” Such a strategic use of social media included the nature of the content produced, the ways in which it was managed, and the use of language to create a more sophisticated image of the party, highlighting values of hard work, effective communication, and trust.

A remarkable approach that exemplifies the superiority of the RNI’s online campaign was the creativity the party displayed in producing short videos that were not only suitable for social media, but that also targeted various groups. A good example is a short video which exceeded two million views and mainly addressed first-time voters, encouraging them to vote by explaining the new voting process in a simple, humorous, and casual way (RNI 2021a). Similarly, the party has produced several creative short videos in collaboration with some famous Moroccan actors (RNI 2021b). These videos were in the form of movie clips that reflected daily life interactions, using both Moroccan Arabic and Amazigh languages while encouraging citizens to vote and highlighting the party’s vision and logo.

Another innovative strategy that the RNI used was to combine offline and online realms. While the RNI has spent generously on its digital campaign, it has also invested in offline campaigning. Akhannouch’s initiative 100 Villes, 100 Jours (“100 Cities, 100 Days”) is a significant example. As its name suggests, RNI supporters visited 100 cities to meet citizens, listen to them, and collect their proposals. This initiative has allowed the party to connect with a larger public in various cities while it constituted a rich source of content for its online platforms. A considerable amount of the RNI’s online content was born out of this initiative’s testimonies from all over the country, which demonstrated the party’s wide reach. Moreover, Akhannouch announced the outcomes of the initiatives during an offline event, whose coverage provided extra material for their online campaign. By promoting the RNI’s offline activities on social media platforms, the party succeeded in highlighting its ability to communicate with the citizens in a time when its main competitor, the PJD, was suffering from these particular flaws.

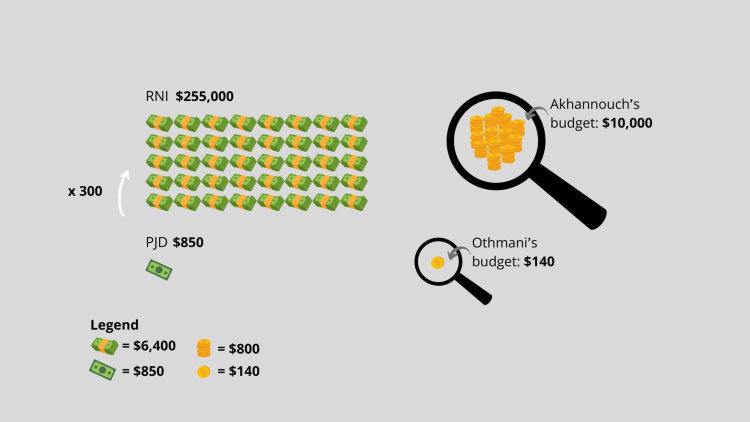

One of the most striking indicators of the disparity between the two parties’ media use is the resources allocated for their electoral campaigns. The RNI spent generously on advertising, which boosted its online presence and outreach, as more ads for the RNI compared to any other party ran on various websites around election time. This implies that the party might have benefitted from data science to better understand, if not predict, the behaviour of its target audience on common social media portals. Political parties and candidates also varied tremendously in the amount of money spent on their online campaigns. For instance, the RNI allocated USD 252,633 for its digital campaign, USD 10,010 of which was spent just on Aziz Akhannouch’s page on the RNI official website. By contrast, the PJD spent a measly USD 851 on its entire official site, only USD 138 of that going to Saadeddine Othmani’s page.

Figure 4. Digital Campaign Budgets of the RNI and the PJD

Source: Najdi 2021: visualisation by Lena Richter.

Note: $ = USD.

The RNI’s approach to its electoral campaigning reflects its conviction of using the online sphere to mobilise voters and reach out to a larger public. This is a lesson that the RNI’s leader must have learnt after the boycott campaign of 2018 which targeted, among others, his own company, Afriquia. The following year, Akhannouch spent generously and hired experts to use the same online tools that were used against his company to prepare for the parliamentary elections scheduled for 2021. Compared to the RNI, the PJD has invested very little in digital campaigning. While the PJD also used social media platforms during the elections, it relied mainly on the “ordinary” expertise of its volunteer members and supporters to produce and promote its digital content (Al-Quwiti 2021).

The Future of Social Media Campaigning in Morocco

The differences in the use of various media during the last elections has proved the power of online campaigning as well as the persistence of its offline counterpart, even in times of crisis. Accordingly, the political actors and parties that invested in both online and offline campaigning were more visible and, therefore, increased their chances of success in the elections. This was a strong contributing factor in the victory of the RNI over the PJD. Overall, Morocco evinced a big change in terms of using social media in the elections, but since the last elections took place under exceptional circumstances, it is difficult to draw comprehensive conclusions about the efficiency of online campaigns in “normal times.” Put differently, online campaigning may not remain as central as it was in the last elections; instead, a hybrid approach of online and offline communication is expected to be utilised in the next elections. The specific conditions under which the Moroccan elections of 2021 took place have revealed crucial insights for the organisation of voter mobilisation both offline and online. Today, social media is no longer a tool exclusively used by Morocco’s civil society to demand accountability for political decisions. Online campaigning has developed into a powerful avenue that has been increasingly recognised by political parties as crucial to winning elections.

The eager consumption of social media by citizens remains crucial to providing a comprehensive picture of the elections. During the campaign, for instance, some media outlets hosted political debates with various parties’ leaders, broadcasting these meetings live on social media. Given the interactive aspect of these platforms, namely the comments section, observers were able to get a better idea of the social media users’ opinions not only of the parties’ agendas but of the idea of voting and politics in general. Also, during the 2021 elections, social media was present in places where international election observers, who mostly stayed in the areas around Casablanca and Rabat, were absent: social media users were able to bring attention to protests taking place in some regions during the closing of polling stations. This helped to complement and sometimes contradict the prevailing narratives of the elections, which were elsewhere described as “calm, orderly, and transparent” (Council of Europe 2021). Furthermore, even after the elections, social media users kept the politicians on their toes by continuing to remind the public of the winning RNI’s promises, which were already criticised for being too ambitious.

Whether in offline or online spheres, citizens’ voices constitute an indispensable element in the electoral process. Thus, their right to freedom of speech should not be restricted. This implies that any legal procedure that criminalises consumer boycotts or other forms of online activism should be prevented. The opportunity to express one’s viewpoints online might also be attractive to groups within the Moroccan population vulnerable to disenfranchisement: most notably, members of the Moroccan diaspora, along with those who face obstacles in accessing polling stations, such as persons with disabilities.

While the use of social media is no panacea for inequitable access to political participation, it does offer new opportunities. Online campaigns during the 2021 elections were found to be efficient in maximising the visibility and thereby the chances of success of some parties and candidates over others. Moreover, these campaigns might stimulate voter participation among different groups, as a large part of the population can be reached via digital campaigning. Yet, while social media has an almost inherent ability to reach out to certain groups, namely young people, other groups are often excluded.

The power of social media also comes with risks. The huge discrepancies between political parties in terms of their financial capabilities tends to breach the principle of equal chances, which is at the core of democratic elections. Therefore, it is crucial to have legal and institutional frames to guarantee fair electoral campaigns. In this regard, it is a good first step that the High Council of Audiovisual Communication issued new decisions to monitor the electoral campaigns to ensure neutrality and pluralism between political parties in public media (Haute Autorité de la Communication Audiovisuelle 2021). Nevertheless, in light of the hegemony of some private media outlets over others, more independent institutions, such as the Court of Accounts, should be involved in controlling the public finances, ensuring more transparency, accountability, and thereby re-establishing confidence in politics among the broader public in Morocco.

Footnotes

References

Al-Mamlaka al-Maghribiyya [Kingdom of Morocco] (2021), Intikhabat [Elections], accessed 15 November 2021.

Al-Quwiti, Sana’ (2021), Ja’iha kuruna wa fadha’ al-shabab al-mufadhdhal…al-hamalat al-raqmiyya tafridh nafsaha fi al-intikhabat al-maghribiyya [Corona Pandemic and the Favourite Social Space of the Youth … Digital Campaigns Impose Themselves During the Moroccan Elections], Aljazeera, 2 September, accessed 11 November 2021.

Council of Europe (2021), Congress Concludes Electoral Observation Mission in Morocco, 9 September, accessed 10 November 2021.

Haute Autorité de la Communication Audiovisuelle (HACA) (2021), Supervision by The HACA of The Electoral Campaign in The Audiovisual Media: Equitable Access for Parties to the Air and Impartial Media Treatment to Preserve Voters’ Freedom of Choice, 3 August, accessed 12 November 2021.

Mekouar, Merouan (2018), Beyond the Model Reform Image: Morocco’s Politics of Elite Co-Optation, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, June, accessed 11 November 2021.

Najdi, ‘Adil (2021), ‘Al-dijital’ yafridh nafsahu fi al-intikhabāt al-maghribiyya 2021. Al-‘Arabi al-Jadid [The ‘Digital’ Imposes Itself in the Moroccan Elections 2021], in: The New Arab, 8 September, accessed 12 November 2021.

RNI (2021a), Ila nawi tasawwat, had al vidiyu kay-yashrah kayfiya al-taswit nahar 8 shutanbir … allī ka-takhtālaf ‘ala kull al-marrat alli fatu! [To the One Who Intends to Vote, this Video Explains How to Vote on the Day of September 8th...Which is Different From all the Previous Times!], accessed 30 November 2021.

RNI (2021b), Al-halaqa al-ula min kabsula al-fidiraliyya al-wataniyya li-l-fannanin al-tajammuʿiyyin al-khaṣsa bi-tashjiʿ al-muwatinin ‘ala al-taswit [The First Episode of the Capsule of the National Federation of Collective Artists Aiming at Encouraging Citizens to Vote], accessed 30 November 2021.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Douhan, Hayat, Eleonora Landucci, and Lena Richter (2022), Social Media in Morocco: From Grassroots Activism to Electoral Campaigns, GIGA Focus Middle East, 4, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfme-22042

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.