- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- From Crisis to Comeback: The Global Story of Re-Democratisation

GIGA Focus Global

From Crisis to Comeback: The Global Story of Re-Democratisation

Number 4 | 2025 | ISSN: 1862-3581

Despite a retreat of democracy globally, all hope is not lost. Countries can and do return to democracy after setbacks. Re-democratisation is not rare, demonstrating that democracy can be rebuilt even after serious decline. As the German government looks for further partners in the Global South, it is important to recognise not only where democracy is declining but also where it is being rebuilt.

After its decline due to attacks from within, all efforts at defending and promoting democracy fall under the rubric of “re-democratisation,” including the successful re-establishment of democratic principles, institutions, and elections.

While watchdog organisations and media have highlighted a decade of global de-democratisation, autocracy is not the endpoint. As visible in the data, nearly one-third of affected countries have returned to democracy – meaning only slightly fewer than those that have not. This shows that re-democratisation, though never assured, is possible; as such, it warrants close international attention.

Between 1989 and 2023, re-democratisation followed regional patterns. Asia led with 9 of 19 countries returning to democracy. In Latin America and the Caribbean, only 3 out of 13 cases re-democratised. Other parts of the world show more variance: while democracy returned in some instances, in others it did not; many countries remain in flux.

Contrary to expectations, even cases with weak democratic institutions have recovered. The duration of the period of de-democratisation appears more important for ultimate success than the depth of initial decline.

Policy Implications

Re-democratisation offers not only hope but also a key opportunity for those seeking to support international partners old and new. For Germany, aiding democratic recovery in the Global South can reinforce values and alliances amid a series of democratic crises. Democratic actors must consistently back pro-democracy forces and avoid resorting to undemocratic means, even in democracy’s defence.

Re-Democratisation Exists

Global media as well as watchdog organisations (Gorokhovskaia and Grothe 2024; EIU 2025) have been warning of a global crisis of democracy for more than a decade now. Prominent cases from Hungary to India, Indonesia through the United States confirm the impression of democracy being in retreat. But does this mean democracy as a whole is doomed? We took a closer look at periods of autocratisation across 74 cases between 1989 and 2023. Our findings were surprisingly hopeful. In fact, whereas processes of autocratisation have played out in numerous countries worldwide, their trajectories have varied considerably. In some instances, the erosion of democratic institutions culminated in authoritarian consolidation. In others, the mobilisation of pro-democracy actors either curtailed such dynamics at an early stage or subsequently enabled democratic recovery. The most recent wave of protests in countries from Bangladesh (2024) to Nepal or Madagascar this year further support our assessment.

Examples of democratic decline captured by the dataset include Ecuador (2007–2013), Guatemala (2018–2023), Lesotho (1994–1995, 2015–2017), Madagascar (2006–2010), and the Philippines (2001–2005, 2016–2023). In Madagascar, for instance, President Marc Ravalomanana used a referendum on constitutional reform to increase his powers and dissolve parliament during his second term in office. Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa, meanwhile, began to dismantle democracy at home shortly after his election in 2007. Correa, who enjoyed widespread popular support, presented himself as an alternative to the political establishment. Via public referenda, he introduced various constitutional changes, thereby concentrating power in his own hands and gaining control over the legislature and judiciary (De la Torre 2015) while also attacking the media and restricting civil society.

Guatemala’s democratic polity has long struggled with corruption. When the United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was established in 2007, there were hopes that democracy and trust in institutions would be strengthened. However, disinformation campaigns and corruption scandals continued to erode faith in the government. This became evident in 2019 when then-president Jimmy Morales intimidated the Constitutional Court into ruling against the renewal of the CICIG’s mandate. This process has continued ever since, with President Alejandro Giammattei (2020–2023) limiting mechanisms of political accountability and impairing media diversity. A pact between Giammattei, senior military officials, members of Congress, and business elites undermined democratic oversight and expelled the UN-backed anti-corruption body. Judges and lawyers involved in investigations against corruption or war crimes were persecuted, as were critical journalists too. Although Giammattei refrained from pursuing constitutional amendments that would allow him a further term in office, the electoral process was still manipulated – with opposition candidates being barred from running on tenuous grounds (Stuenkel 2023). Furthermore, even supposedly consolidated and stable democracies, such as India or the US, have seen their democracy ratings drop. Donald Trump has turned to ruling by decree in his second term, ignoring inconvenient court rulings and interfering with federal states’ own competencies all while attacking civic spaces.

All these examples illustrate what is typical of contemporary autocratisation: the dismantling of democracy from within at the hands of elected officials. While processes of de-democratisation are similar across cases, however, outcomes are not. Looking at the “Regimes of the World” classification (Varieties of Democracy v14), the Philippines (2004–2009) and Madagascar (2010) became autocratic regimes whereas Ecuador’s and Lesotho’s trajectories ultimately proved different. In the South American country, Correa’s abolishment of presidential term limits paved the way for his indefinite re-election. Yet, surprisingly, he did not run in the 2017 polls. Instead he picked his former vice-president as successor, who then initiated re-democratisation and launched a formal investigation of Correa for abuses of office.

Lesotho experienced two democratic crises initiated not by elected leaders but unelected powerholders. The first occurred in 1994, when King Letsie III dismissed Prime Minister Ntsu Mokhehle’s government and dissolved parliament (Southall 2003). Though not a military coup in the traditional sense, rather a royal intervention, it was a direct constitutional breach supported by parts of the military. From 2015 until 2017, Lesotho slid into a second bout of crisis as intense rivalry within the fragile coalition government combined with the military’s defiance of civilian authority. This entanglement of partisan conflict and interference by the security forces undermined democratic rule and pushed the country into renewed instability. In both instances, democracy was eventually brought back to Lesotho through elite negotiations supported by regional mediation.

Cases like Ecuador and Lesotho suggest that the outcome of democratic crisis is not predetermined; in other words, not all countries suffering attacks on their democratic nature end up as autocracies. Some manage to fend off such assaults, others halt the decline, and a few are even able to restore key aspects of democracy. Such recovery can be referred to as “re-democratisation.” Are, then, Ecuador and Lesotho rare exceptions or part of a broader trend?

Re-Democratisation Happens More Often Than One Might Think

The world is full of stories of democratic crisis. These circumstances manifest in a number of different ways: elections becoming less free or fair, courts and parliaments losing their independence, more power being concentrated in the hands of the executive, and/or civil society and media facing growing restrictions. We identify these episodes of autocratisation using the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) from the V-Dem project (v14) (Coppedge et al. 2024). The EDI captures the quality of democracy, as observed in free and fair elections, checks on executive power, and core freedoms of association, expression, and information. The Episodes of Regime Transformation (ERT) dataset (Edgell et al. 2020) then identifies crises as sustained and significant declines per this index, signalling autocratisation within electoral democracies.

Yet, what is often overlooked are the stories of democratic recovery. Countries do not always quietly slide into autocracy never to return. Some fight back, and some even manage to rebuild. In our data, a re-democratisation episode is recorded when an increase in EDI score is noted within ten years of the onset of democratic decline. This way, we can capture when democratic quality first begins to recover: fair and free elections are restored, checks on power strengthened, and space for citizens to participate in politics unimpeded opens up again.

Figure 1. Distribution of Episodes

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on ERT dataset (Edgell et al. 2020); visualisation by Eduardo Valencia, T4T.

As shown in Figure 1, the global picture is more balanced than one might expect. Just over one-third (35.1 per cent) of countries that experienced such a crisis have not returned to democracy since. However, almost the same number again have managed to re-democratise (32.4 per cent); another third are still in the middle of that struggle (32.4 per cent). In short, nearly one-in-three cases end in democratic recovery.

Take Brazil, for instance: The country went through a deep political crisis starting in 2016, marked by the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff and the rise of Jair Bolsonaro. During the latter’s presidency, democratic checks and balances came under serious pressure. After the 2022 elections, though, the South American nation took a different turn. Despite Bolsonaro’s followers rioting and storming Congress shortly after the inauguration of President Lula Da Silva, Brazil still returned to the path of democracy. Strong resistance, especially from institutions like its courts of law, makes renewed impetus towards democracy clear here (Reder 2023).

Guinea-Bissau is another intriguing case. After a period of democratic decline marked by elite infighting and institutional paralysis (2012–2013), the West African country began to recover in 2014. This turnaround was characterised by political negotiations, electoral processes, and external pressure from regional actors. Civil society groups, including religious leaders and citizen movements, supported the call for elections and helped mediate between factions. Although its courts have remained weak since de-democratisation, the judiciary began to show signs of independence from 2014 onwards already. Despite fragile institutions and a low starting level of democratic quality, Guinea-Bissau managed to gradually recover – showing that even vulnerable democracies can rebound.

At the same time, many countries are still stuck in democratic decline. Even Mauritius, once a relatively stable democratic polity, has regressed – for example, following former prime minister Pravind Jugnauth’s concentration of power in his own hands. Alongside a crackdown on free media and civic spaces, as well as vote rigging, Mauritius became an “electoral autocracy” in 2023. The Philippines is another country still enmeshed in democratic decline. Since 2016, first under Rodrigo Duterte and later Ferdinand Marcos Jr., it has seen rising executive dominance, weakened checks and balances, and widespread attacks on media freedom and civil society. Extrajudicial killings during Duterte’s war on drugs and efforts to undermine independent institutions have contributed to a steady erosion of democratic standards. The Philippines remains an “electoral autocracy” (since 2023), with no clear signs of recovery.

Re-Democratisation: Regional Overview

When looking at countries that have experienced democratic crisis, both clear patterns and notable contrasts are evident across world regions (see Table 1 below). Asia-Pacific stands out with the highest share of re-democratisation cases at 47 per cent (9 out of 19). Nearly half of all those affected recovered their democratic quality eventually. This indicates a relatively strong tendency for countries in this region to restore democratic governance after periods of decline when compared to elsewhere in the world. In addition, successful pro-democracy protests in sclerotic political regimes from Sri Lanka (2022) to Bangladesh (2024), or Nepal this summer, underline the region’s striving for political change.

In contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as non-OECD Europe and the Caucasus, show much lower re-democratisation rates, at 23 per cent (3 out of 13) and 25 per cent (3 out of 12), respectively. With five each, both regions also have a relatively high number of instances of ongoing democratic decline. Sub-Saharan Africa presents a more evenly distributed picture. About one-third of cases have re-democratised (8 out of 26), another third have not (9), while the remainder are still in decline (9). The Middle East and North Africa have only four cases with two without re-democratisation. The rest is split evenly between re-democratisation and ongoing decline. This small sample size makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions, but underscores the mixed outcomes witnessed in the region.

Table 1. Distribution of Episodes by World Region

Region | Re-Democratised | Not Re-Democratised | Ongoing | Total |

Asia & Pacific | 47% (9) | 32% (6) | 21% (4) | 19 |

Latin America & Caribbean | 23% (3) | 38% (5) | 38% (5) | 13 |

Middle East & North Africa | 2%% (1) | 50% (2) | 25% (1) | 4 |

Non-OECD Europe & Caucasus Sub-Saharan | 25% (3) | 33% (4) | 42% (5) | 12 |

Sub-Saharan Africa | 31% (8) | 35% (9) | 35% (9) | 26 |

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on ERT dataset (Edgell et al. 2020).

These statistics do not reflect the overall state of democracy in each examined region. Rather, they speak only to the group of countries that experienced democratic crisis at some point between 1989 and 2023. Still, numerous instances of recovery being seen across world regions prompts the question: Why do some countries manage to bounce back while others do not?

Patterns of De-Democratisation

In comparing 24 cases of countries successfully returning to democracy, we are able to identify three patterns that help explain the when and how:

Re-democratisation is not time-bound

Prolonged autocratisation does not out rule re-democratisation. Out of the 24 cases, 8 returned to democracy within the first five years after the decline started, while 16 did so after five or more years. Rapid recoveries include Burkina Faso (2014–2016), which began to rebound just two years after decline first set in. By contrast, Tunisia (2013–2023) only saw the onset of re-democratisation a full decade later. This shows that while early recovery is possible, re-democratisation by and large takes a while to materialise. Thus, even when authoritarian rule has been consolidated for many years, opportunities for democratic resurgence can still emerge. The evidence, therefore, challenges the view that democracy must return quickly if decline is not to be terminal. Instead, both rapid and delayed recovery are viable pathways back to democracy.

Recovery is possible even for weak democracies

Prior democratic strength can aid swift recovery. Countries that were more democratic before decline took hold often bounce back with greater speed. We observe this, for example, in Brazil (2016–2023), which had high democracy scores on entering crisis and managed to return to democracy in a relatively short space of time.Strong democratic quality is, though, not a necessary condition for re-democratisation. Fiji (2000–2003, 2006–2015), Guinea-Bissau (2012–2019), and Mali (2007–2014) all had relatively weak democratic foundations and low democracy scores prior to decline. Still, they regained democratic qualities and rebuilt core institutions. This challenges the assumption that only strong democracies can bounce back after crisis. Weak starting points create obstacles but certainly do not rule out recovery entirely.

Plummeting does not always mean the end of democracy

Even countries experiencing steep drops in democratic quality recovered, like Mali (2007–2014) and Tunisia (2013–2023) for instance. By contrast, those suffering both deep decline and long periods of authoritarian rule, such as Venezuela (2002–2012) and Nicaragua (2007–2017), rarely return to democracy. Thus, both the depth and duration of these events shape the chances for eventual replenishment.

In sum, across world regions, we find instances of both quick recovery and long, drawn-out struggle. Moreover, re-democratisation occurs not only in countries with a strong democratic past but also in those with weaker such traditions. Even in cases of severe decline, the outcomes of democratic crisis are not pre-determined. Figure 2 below outlines the trajectories to democracy over time and across countries. To understand how exactly recovery works, then, we must ask: Who drives it?

Figure 2. Episodes of Re-Democratisation – Timeline by Country

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on ERT dataset (Edgell et al. 2020); visualisation by Eduardo Valencia, T4T.

Processes of Re-Democratisation

Re-democratisation is highly context-specific. This makes it difficult to draw general conclusions about its occurrence. Those who stop autocratisation and promote democracy vary according to setting. The following three illustrative cases show how different actors or institutions contribute to re-democratisation. Ecuador is an example of public pressure combined with elite defection. Lesotho illustrates the importance of regional organisations in supporting local pro-democracy actors. Guatemala showcases the power of mass protests against political and economic elites in the most difficult circumstances.

Ecuador

The South American country has suffered from constitutional instability throughout its history. Some 20 Constitutions since independence in 1830 illustrate this. They are meant to last and establish institutions, principles, and values that will endure irrespective of power changing hands. The rule of law is established hereby, creating reliability of expectations. When Constitutions are changed frequently, uncertainty prevails. Accordingly, in Ecuador, constitutional guarantees and the rule of law have continued to be unstable. The executive frequently interferes in courts, whose capacity to rein in elected officials’ autocratic tendencies has been compromised as a result. What transpired under Correa is a good example. When first elected in 2006 he was widely popular, representing a counter pole to established political forces (De la Torre 2015). He remained so even after repeatedly changing the Constitution and attacking the separation of powers, the media, and civil society organisations. Together, his popularity and successful constitutional engineering made it unlikely that the judiciary or the opposition would successfully stand in the way of autocratisation.

It was only when economic crisis and reports in the foreign press about corruption scandals in the country came together that he lost some support. Under pressure from street protests and civil society, he decided not to run again in 2017. Instead his handpicked successor, Lenín Moreno, went on to win. Surprisingly, once in office, Moreno turned against Correa and initiated a process of re-democratisation, including strengthening the judiciary (De la Torre 2018). In summary, it was popular discontent sparked by economic crisis that strengthened civil mobilisation, which opened up the path for a return to democracy.

Ecuador reverted to democracy by (re)strengthening its institutions, in particular the judiciary. However, Moreno too kept bending constitutional rules. Furthermore, his policies included defunding the prison system, as contributing to the country’s current security issues. As a result, Ecuador re-democratised but has recently entered crisis again. The polarisation between Correa’s supporters and his opponents, as well as the notorious disrespect for the Constitution, rule of law, and democratic institutions, have accelerated under current president Daniel Noboa. In fact, designed as a response to the country's growing organised-crime problem, Noboa’s security policies rely on states of exception and mass detentions that forego human rights, thus further contributing to the erosion of democracy. Nonetheless, the judiciary still demonstrates its independence (as under Correa’s presidencies), and has recently become more active – for example, in recognising indigenous rights.

Lesotho

In the Southern African country, re-democratisation came about differently in both episodes we looked at in detail. Here, a combination of internal actors – elites from within the monarchy, the military, and politics – dominated in both the breakdown and the rebuilding of democracy. Thus, Lesotho is one of the few examples where democracy returned not through courts or civil resistance but elite negotiation and regional diplomacy.

During its first episode of democratic crisis in 1994, regional actors stepped in within weeks. Back then, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) – led by Botswana, South Africa, and Zimbabwe – mediated a return to the constitutional order (Matlosa 2010). The government was reinstated, and King Moshoeshoe II, Letsie’s father, brought back to the throne. Although political stability took time, democratic quality improved steadily after 2002 when new electoral rules helped ease long-standing tensions – that is, until the next crisis began in 2015.

During this second, more recent episode of democratic crisis it was again the SADC who would take the lead. This time, South African deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa brokered negotiations that led to fresh elections in 2015 and again in 2017 (ACCORD 2015). While Lesotho’s political system remains unstable, its democratic credentials have not collapsed entirely. In 2022, elections produced a peaceful transfer of power from Moeketsi Majoro to the businessman Sam Matekane. During this period, Lesotho’s democracy improved modestly. Although recovery was weaker than following the earlier episode, it was enough to reverse the decline.

In both instances, civil society played only a marginal role in proceedings. The judiciary, constrained by political interference, was no bulwark against democratic decline either (Shale 2018). Instead, re-democratisation came from above. Elite negotiations among senior military officers, party leaders, and members of the monarchy, supported by external mediation, kept the political system from sliding further into the mire and eventually steered it back onto the path of democracy.

Lesotho’s experience highlights how outside pressure and elite recalibration can fill the gap when domestic institutions are too fragile to defend democracy themselves. Although this may not produce deep reform, it can prevent complete collapse; sometimes that is enough to keep the door open to eventual recovery. The limited depth to the country’s most recent recovery, though, suggests that without stronger internal democratic forces then the situation will remain delicate.

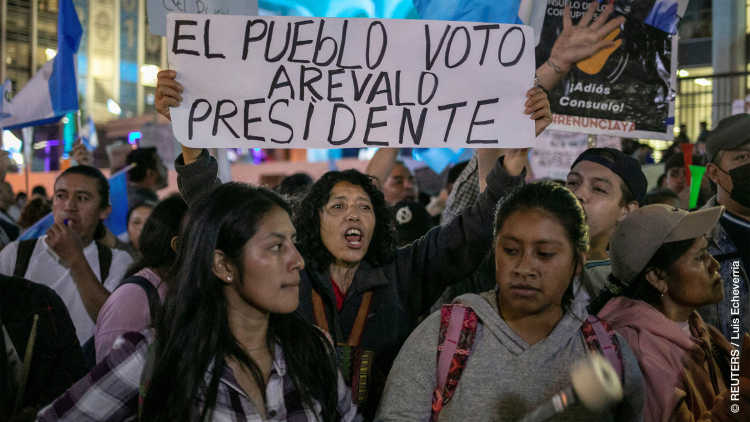

Guatemala

Although the Central American country’s Constitution excluded Giammattei from re-election in 2023, he maintained control over parliament and the judiciary. With critical journalists behind bars and prospective opposition candidates excluded from running, it was expected that Sandra Torres, his protégée, would win the presidency and continue Giammattei’s chosen political course. As such, the prospects for democracy were bad before the situation took an unexpected turn: underdog candidate Bernardo Arévalo emerged as the winner. Despite efforts by Attorney General Consuelo Porras, notorious for undermining anti-corruption investigations, to annul the elections, mass mobilisations – particularly by indigenous communities – ensured Arévalo’s inauguration went ahead in January 2024 (Kurtenbach, Reder, and Ripplinger 2024). His victory sparked new hope for Guatemalan democracy, though efforts at re-democratisation continue to run counter to the networks of corruption deeply entrenched in the country’s social fabric.

Notwithstanding some economic growth and increased public security, Arévalo’s popularity rating has dropped significantly: from 78 per cent in 2024 to 39 per cent in January 2025 (CID GALLUP). Without the necessary allies in the legislature and judiciary, his government’s hands are tied. As Congress is fragmented, lawmaking is slow and complicated, delaying necessary projects. Meanwhile, Arévalo finds himself under constant attack from the public prosecutor’s office. To rule more effectively, he could have the attorney general dismissed or start to rule by decree. This, however, would mean that he himself interfered with the separation of powers, disrespecting basic democratic principles (InSight Crime 2025).

Re-democratisation can, then, take very different paths. In Ecuador, the return to democratic governance was facilitated by a combination of a change of political leadership, growing public discontent, and sustained pressure from civil society. In Lesotho, democracy was restored via elite negotiations in tandem with regional counterparts becoming closely involved – thus with little help from its own courts or civil society. In Guatemala, civil society drove re-democratisation against all odds, but the process remains inhibited by endemic corruption. There is no one-size-fits-all solution: who spurs democratic recovery, and how it unfolds, vary from place to place.

What Germany and the European Union Can Do to Assist

German and European foreign policy should be grounded in the recognition that democratic recovery is not only possible but already happening. Thus, there is ample room for international support. Six concrete observations stand out here:

Even fragile democracies can recover if given space and backing. They should not be overlooked. Some of the most successful instances of re-democratisation occurred in countries with low starting levels of institutionalisation.

Re-democratisation is not time-bound. While some countries rebound quickly, most only begin to do so after many years of decline. Early engagement remains pivotal to preventing authoritarian consolidation, but long-term support is equally vital. Sustained involvement ensures democratic forces are ready when opportunities for recovery eventually arise.

Re-democratisation is context-specific. In some cases, courts and civil society lead the change; in others, it is elite negotiations and regional diplomacy that prevent collapse. Cases like Ecuador and Guatemala illustrate the risk of democratic backsliding on the part of actors who initially promised reform. Thus, German and EU democracy promotion must be flexible, recognising different recovery paths and constellations. Standardised toolkits are unlikely to succeed where political dynamics are highly localised.

Regional organisations often play a decisive role in such matters. German and European diplomatic and financial backing for regional mediation can be the difference between recovery and collapse. Examples include the African Union and the SADC, which have played key roles in stabilisation efforts in the past.

Invest in democratic depth, not just recovery. Re-democratisation does not guarantee democratic consolidation. As seen in Ecuador, Guatemala, and Lesotho, surface-level recovery may mask deeper institutional weaknesses. External support should thus go beyond just advocating for elections, also striving to strengthen the rule of law, judicial independence, civil society, and civic education while tackling elite-driven governance – even when the path forward is politically inconvenient. Without internal consolidation, any return to democracy remains vulnerable.

Defend democracy within established boundaries. The cases of Ecuador and Guatemala demonstrate the dilemmas faced by those attempting to protect and rebuild democracy. While it may seem necessary to exclude non-democratic actors or bend the rules, such actions ultimately undermine both plurality and public trust in democracy.

Footnotes

References

ACCORD (2015), Appraising the Efficacy of SADC in Resolving the 2014 Lesotho Conflict, 23 October, accessed 15 October 2025.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, et al. (2024), V-Dem V14, SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4774440, Rochester, NY, 7 March, accessed 15 October 2025.

De la Torre, Carlos (2018), Latin America’s Shifting Politics: Ecuador After Correa, in: Journal of Democracy, 29, 4, 77–88, accessed 16 October 2025.

De la Torre, Carlos (2015), Populist Playbook: The Slow Death of Democracy in Correa’s Ecuador, in: World Politics Review, 19 March, accessed 16 October 2025.

Edgell, Amanda B., Seraphine F. Maerz, Laura Maxwell, et al. (2020), Episodes of Regime Transformation Dataset (v2.0) Codebook, University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute, accessed 16 October 2025.

EIU (2025), Democracy Index 2024. What’s Wrong with Representative Democracy?, accessed 16 October 2025.

Gorokhovskaia, Yana, and Cathryn Grothe (2024), Freedom in the World 2024. The Mounting Damage of Flawed Elections and Armed Conflict, February, Freedom House, accessed 15 October 2025.

InSight Crime (2025), Arévalo, One Year On: Is Guatemala’s President Losing the Fight Against Corruption?, January, accessed 15 October 2025.

Kurtenbach, Sabine, Désirée Reder, and Alina Ripplinger (2024), Guatemala: A Vote for Turning the Tide, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), accessed 15 October 2025.

Matlosa, Khabele (2010), The Role of the Southern African Development Community in Mediating Post-Election Conflicts: Case Studies of Lesotho and Zimbabwe, in: Khabele Matlosa, Gilbert M. Khadiagala, and Victor Shale (eds), When Elephants Fight: Preventing and Resolving Election-Related Conflicts in Africa, Johannesburg: EISA, accessed 15 October 2025.

Reder, Désirée (2023), Gewalt in Brasilia: “Spaltung auch in Staatsinstitutionen”, interview by tagesschau.de, 9 January, accessed 15 October 2025.

Shale, Itumeleng (2018), Report of the 2018 Fact-Finding Mission on Effecting Judicial Reforms to Secure the Stability, Independence and Accountability of the Judiciary for the Enbhancement of the Rule of Law in Lesotho, African Judges and Jurists Forum, accessed 15 October 2025.

Southall, R. (2003), An Unlikely Success: South Africa and Lesotho’s Election of 2002, in: The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41, 2, 269–296, accessed 15 October 2025.

Stuenkel, Oliver (2023), Guatemala’s Farcical Elections Mirror Broad Democratic Backsliding in Central America, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 22 June, accessed 16 October 2025.

Editor GIGA Focus Global

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Global

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Reder, Désirée Marlen, and Monika Onken (2025), From Crisis to Comeback: The Global Story of Re-Democratisation, GIGA Focus Global, 4, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfgl-25042

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.