- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Abortion Rights in Latin America: An Unsettled Battle

GIGA Focus Latin America

Abortion Rights in Latin America: An Unsettled Battle

Number 3 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Despite feminist movements’ many steps forward in Latin America, abortion rights remain an issue where political clashes continue. While other equal rights advances have been attained without any subsequent “rolling back,” abortion rights have exhibited a pendular back-and-forth dynamic in many countries of the region. They often become a high-profile public issue in polarised political contexts. This also affects the work of NGOs and development agencies.

Abortion rights are one of the most polarising and politically contentious issues in the Americas today, and one that is often aligned with left-wing (pro-liberalisation) and right-wing (pro-prohibition) positions. National and transnational advocacy on both sides has intensified, with little room left for meaningful dialogue.

Latin American and Caribbean countries exhibit some of the world’s harshest and most prohibitive abortion laws.

The legal status of abortion varies widely within the region, and pressure to change this status arises frequently. Argentina, Chile, Dominican Republic, and Mexico have all seen significant legal changes related to abortion in the last five years. While Chile and Argentina have taken steps towards legalisation, an attempt to legalise abortion in the Dominican Republic – only when there is a risk to the woman’s life – is still pending Congress approval. Mexico’s federal system has seen some states toughen abortion restrictions, while only one state has moved in the opposite direction.

While particular religious organisations constitute the core pressure group for restricting abortion rights, calls for liberalisation have received broad support among urban and secular sectors of society.

The pendular character of abortion rights can be expected to continue as part of the frequent left and right swings on the continent.

Policy Implications

Institutions and NGOs working in the field of reproductive rights face an ever-changing legal environment, which poses major threats to their activities. Especially those organisations dependent on US funding frequently suffer from the so-called “global gag rule,” which is enacted or repealed depending on the party in power in Washington, as it prohibits aid or partnerships with institutions that promote abortion rights.

Decades of Controversy

The practice of voluntarily interrupting a pregnancy has long been controversial. Where socially conservative, traditional mindsets persist, abortion remains one of the most contentious topics in sociopolitical life. We see this acutely in Latin America and the Caribbean. Legal prohibitions on abortion, however, do not keep abortions from happening. Instead, an abortion often becomes an illegal and risky procedure which puts the woman’s life, health, or future fertility at risk. Research data from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that illegalising abortion does little to actually prevent abortions (Shah, Ahman, and Ortayli 2014; WHO 2012: 87–90).

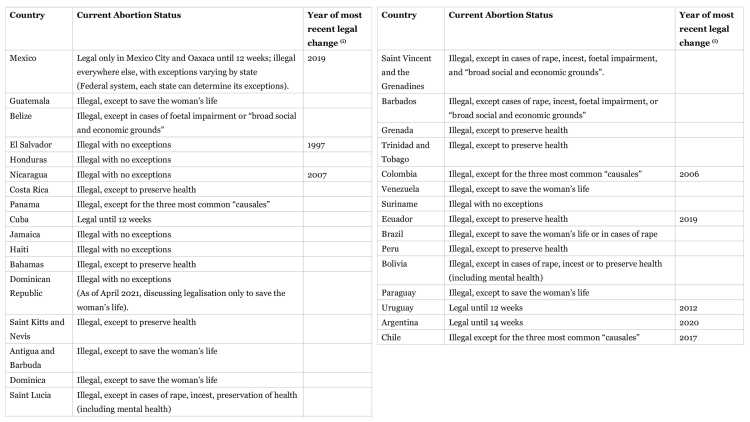

A closer analysis of the legal landscape of abortion (throughout the world in general and the Americas in particular) shows that the issue cannot be simplified into abortion merely being “legal” or “illegal.” Instead, we find laws with various nuances, including differentiated sanctions depending on context and circumstances (or differentiated between the woman and the personnel carrying out the abortion), or general prohibitions with exceptions. These exceptions to abortion bans are often called “causales” (causes) in the Spanish-speaking world. The three most common such exceptions are risks to the mother’s life if the pregnancy is continued, fatal abnormalities in the unborn child, or pregnancy as a result of rape.

Other, less common exceptions are pregnancy as a result of incest, risks to the mother’s “health” more broadly (which can include mental health); impairments in the unborn child, even if they are not fatal; or other “broad socio-economic grounds.” Similarly, where abortion is legal, it overwhelmingly tends to be subject to restrictions and regulations, most often gestational limits of approximately 12 to 16 weeks (i.e. how advanced the pregnancy is, counted in weeks).

Mapping the Current Legal Status

Building on the Center for Reproductive Rights’ “World Abortion Laws Map,” Table 1 shows the current legal status of abortion in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean (Center for Reproductive Rights 1992–2021). It also includes the date when the most recent legislative change occurred (where such data is available).

This map also shows where Latin American and Caribbean countries’ legislation stands with regard to abortion:

A Clash of Stakeholders

Diverse stakeholders throughout the region are engaged in advocacy either for or against the legalisation of abortion, often with clear policy change and legislative objectives. These stakeholders range from religious groups and political parties to governmental and non-governmental organisations, as well as prominent individuals from all walks of life. Religious groups in particular do not shy away from trying to influence debates, opinions, and votes, using abortion as a cornerstone of their discourse on family, gender roles, social life, and political activity. While the Catholic Church has always been a bulwark of anti-abortion policies, the rise of evangelical religions has given a new and aggressive boost to campaigns for more restrictive legislation.

In Mexico, Argentina, and Chile, for example, there has been at least one public demonstration every year for the past decade (usually around 8 March, which is International Women’s Day) with legal and accessible abortion as one of the common demands. But this has often also brought counter-protesters demonstrating against abortion, often encouraged by religious organisations, to the streets.

Important political figures and international NGOs have also played an active role in placing the topic on social and political agendas at the local, national, and transnational levels. They advocate for various possibilities on a spectrum that ranges from complete liberalisation to a total ban and the penalisation of abortion, with various nuances in between. Throughout the Americas, advocates opposing legal abortion call themselves “pro-life” and tend to identify with the political right and with a religion (especially Catholicism and evangelicalism); whereas those defending the legality of abortion generally call themselves “pro-choice” and tend to align with leftist policies as well as feminist groups.

These two groups (who indeed see and present themselves as two opposed groups) clash with each other via parallel protests in the streets; opposing proposals for legal reform, which are presented with some regularity; and their support for political candidates who promise further changes to abortion legislation (or conversely, who promise to maintain the status quo). Local chapters of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) – with diverse local names throughout the region – feminist groups, and the numerous national chapters of the Catholics for Choice organisation (Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir) advocate across the continent for the liberalisation of abortion laws. On the other side are numerous “pro-life” advocacy groups, most of them tied to religious institutions. During his 2018 campaign, current Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro stated numerous times that he would “veto any attempt to legalize abortion” (EuropaPress International 2018).

In public protests and media debates, it is possible to identify a strong tendency towards moral reductionism: both sides attempt to summarise their ideas in extremely simplistic and context-devoid manners, using emotionally charged terms such as: “Killing babies is wrong, period,” or “We will never allow this in Chile/ Brazil/El Salvador, here we protect children and the family.” Those pushing for more liberal abortion laws have not been exempt from such moral reductionism and “sloganism” and have also attempted to capture what is an enormously complex issue in short catchphrases: “My body, my rights,” “If I give birth, I decide,” or “Stop the rosaries in my ovaries!” Although simplification is a common way of conveying messages in a protest, the framing of the issue in this case is often highly inaccurate, with inflammatory words or examples of extreme cases exploited in an attempt to generate an emotional response followed by engagement with the issue. As is often the case with contentious topics, the depiction of the ideological opponents as a caricature of their most extreme representatives is a simplistic strategy commonly used by both sides in the abortion debate.

The two groups often have irreconcilable worldviews, and abortion thus represents a symbolic battlefield among a larger set of values. The differences cover a range of social norms regarding gender roles, religious ideas and paradigms on morality, principles about women’s agency over their own bodies, rules about what constitutes acceptable sexual behaviour, the legitimacy of individual reproductive choices, and philosophical views about the point at which “life” begins. Rather than entering into dialogue, both groups appear to be drifting further and further apart, galvanising their ideas into strong demands – often faith-based beliefs – that appeal to fundamental principles.

Transnational Advocacy Alliances

Although the issue of abortion itself is quite nuanced, the discourses seen in protests, both online and offline, are not. Through the use of digital media, advocacy for and against abortion has increasingly become transnational: NGOs and groups of advocates on both sides of the debate seek and create alliances with other advocates abroad and with “sister” or “parent” organisations in other countries (Ginella et al. 2017).

This transnationalisation was made clear in 2018, when Argentina was at the epicentre of protests and debates as Congress debated legalising abortion. Advocates on both sides of the controversy took to the streets in massive protests, simplifying their positions into uniformly coloured bandanas or handkerchiefs (blue for “pro-life” and green for “pro-choice”). These handkerchiefs and corresponding colours were taken as a signifier across the rest of the continent. Today, from Mexico all the way to Chile, on Twitter and in the streets, bandanas identical to those worn in Argentina are used as a personal flag to signal a clear-cut position within the abortion debate.

Paradoxically, most of the activists concerned with abortion who have some degree of expertise on the matter have opinions that fall somewhere between absolute prohibition and absolute permissiveness, with only a few vocal minorities at either extreme. Surveys on the issue show that when pressed to give a more detailed answer, most people have nuanced opinions, also within a range of possibilities (Navarrete and Ramírez 2021). Activists themselves often seem to forget this nuance, rooting their activism in a dichotomous “us versus them,” “good team/bad team” take on the issue. The simplification of the debate into short “tweets,” and effectively into two different colours of clothing accessories, seemingly makes the issue clear-cut. And despite the potential overlap that could exist between their worldviews – for example, much of the “pro-life” camp at least agrees with the “pro-choicers” that the idea should not be to punish women and often also agrees that the state should provide support for vulnerable single mothers – polarisation online and offline has increasingly made it harder to compromise and find common ground. This parting of ways is likely to intensify as politics within the region become increasingly polarised and the potential common ground is forgotten.

The influence of the United States on this issue cannot be overlooked. In North America abortion is highly controversial as well, especially for religious Christian groups and for politically active evangelicals in particular. Latin America has historically been influenced politically, economically, and socially by the USA; this is also the case in the realm of NGOs, development aid, and civil society actors, who exchange information with institutions and advocates from the USA. Examples include the linkages between the US-based Catholics for Choice and its Latin American chapters, Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir, or Pro-Vida in Mexico and American “pro-life” organisations. The US-based International Planned Parenthood Federation has a strong presence in the region, both through its own local offices and its financial support for local institutions that provide contraceptives, family planning services, tests and screenings for reproductive health, and abortion where it is allowed. Similar services are provided by the UK-based organisation Marie Stopes International in Mexico and Bolivia.

The most crucial aspect of US influence, however, is the back-and-forth enactment and repeal of the so-called “global gag rule.” This is a restriction on the provision of abortion services – or indeed even abortion information – by institutions that are recipients of US financial aid (often but not exclusively through USAID, the US government’s development aid agency). The rule is, almost as a matter of routine, reinstated whenever a Republican government is in office and withdrawn when a Democrat governs in the White House. This has happened without exception under every US administration since the “gag rule” was brought into existence in 1984. It is also called the “Mexico City policy,” because it was created within the framework of the UN International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which took place in Mexico City. Also notably, the repeal or reinstatement of the gag rule typically occurs as a “done on Day One of his mandate” kind of change, signifying the importance of abortion as a political signal (Marie Stopes International 2017).

Some still assume that “pro-life” groups in Latin America are comprised mostly of conservative people from generational cohorts over 40 years of age, or that women traditionally have little agency or less active voices. This is, however, inaccurate these days: across Latin America, churches and other traditional groups now manage to mobilise large groups of young people as part of their anti-abortion protests, and women are a strong and growing presence in “pro-life” advocacy groups.

A Back-and-Forth Pendulum

Thus, in quite a remarkable way, abortion is a political flashpoint in the United States and in Latin America, where it has become almost a political tradition that right-leaning governments attempt to restrict access while left-leaning governments aim to liberalise access, like a constant pendulum swinging back and forth. Unlike other issues where vulnerable groups progressively attain rights or social advancements without further mobilisation for “roll-backs,” abortion exhibits this peculiarity of constant change. As a consequence, throughout the region any agreement on legal abortion has a “temporary” feel to it, as though it is subject to change at the next gust of opposing political winds. The fickle nature of abortion laws in the region often affects the provision of services by national and international NGOs and development aid agencies.

Not only does the legal status of abortion within the region vary significantly, but attempts to change this legal status are also constant. Reform projects pushing for more permissive laws are represented throughout Latin America (although many end up being rejected by the congresses), and both these and the more prohibitive abortion laws are regularly challenged in courts. In Mexico (where abortion is under the jurisdiction of subnational politics), the liberalisation of abortion in Mexico City in 2007 led the National Commission of Human Rights to challenge the decision in the country’s Supreme Court (Olivares, Muñoz, and Sevin 2007). Similar challenges are common throughout the region: in Nicaragua, the full ban instituted in 2006 was challenged at the Supreme Court in 2008 – to no avail (Human Rights Watch 2017). The Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACHR) has condemned absolute prohibitions like that of El Salvador. This added fuel to the debate, as the court’s ruling was framed as an infringement on national sovereignty (Deutsche Welle 2021). Against this backdrop, legal changes in any direction appear fragile and temporary.

The following countries have all experienced important changes (or the initiation of reform projects) in their abortion-related laws in the last five years:

In April 2021 in the Dominican Republic, a legal reform that would change the law from a full abortion ban with no exceptions to allowing abortion only in cases of risk to the mother’s life was approved in a first reading by the lower chamber of Congress. At the time of writing, Senate approval is still pending (Human Rights Watch 2021).

In December 2020, Argentina liberalised access to abortion. A previous, unsuccessful attempt, which ignited region-wide protests on both sides, was presented in 2018.

In 2019, the state of Oaxaca in Mexico liberalised access to abortion, joining Mexico City as the only other state with liberalised access (since 2007). At the subnational level, legal reforms are presented regularly in Mexico, and most other Mexican states have banned abortion at some point since 2007.

In 2019, Ecuador began to permit abortion in cases of rape (fully approved only in April 2021).

In 2017, Chile’s law shifted from a total ban with no exceptions to accepting legal abortion in the case of the three most common “causales”: rape, risk to the woman’s life, and fatal abnormalities in the unborn child.

If we go further back than five years, we see more changes: Nicaragua fully banned abortion in 2006 with no exceptions, while Uruguay liberalised access in 2012. Brazil experienced a similar debate in 2012 and the courts decided to keep abortion illegal. The full ban in El Salvador came into effect in 2007, and Colombia decriminalised only the three common “causales” in 2006. Such legislative oscillation can be expected to continue throughout the region.

The case can also be made to “watch for federalism” in countries that have laws that vary at the subnational level, such as Mexico and Argentina. In these countries, national laws establish a basic common ground, but regulations at the subnational level are the final determining factor of what is accepted or prohibited, or of what policies are actually meaningful in practice and are not merely legal principles. Access to abortion is largely determined at the subnational level.

With respect to meaningful access, therefore, the most crucial laws delineating the legality of abortion are not those at the national level but rather at the subnational level, as well as the reforms permitting or prohibiting the passing of more regulations. In Mexico, such blocking attempts are called “blindajes” (“armouring,” as in “to armour” the local constitution against pro-abortion legislative reforms) – for example, all the reforms made over the past decade at the level of the subnational constitutions (in Mexico, each state or “estado” has its own constitution, as well as its own subnational criminal code). The articles in these constitutions have been amended to “protect life from the moment of conception” in an attempt to block any decriminalisation of abortion in the criminal codes or in other regulations.

What NGOs Can Expect

In these shifting contexts and given the uncertain legal situation, NGOs, development agencies, or institutions that deal with women’s reproductive rights including abortion (or even controversial contraception options such as the “morning-after pill”) may face serious problems in their operations and financing, as well as their opportunities for partnerships or government support. In areas where abortion rights become the target of aggressive campaigns by religious and conservative groups, such organisations may face hostility.

A notorious case has been that of the organisation “Women on Waves,” which provides abortion services by sending boats with medical personnel into international waters, just off the coasts of countries where it is prohibited. When such a vessel recently stopped near Guatemala, the Guatemalan courts issued a prohibition and the Guatemalan army announced its intention to impede the boat’s operations, after which the boat abandoned any procedures with Guatemalan women (Feliciano 2017).

In this as in other cases, the uncertain legal situation can threaten the activities of local or international organisations. This is already the case for many NGOs and aid agencies linked with the USA because of the aforementioned gag rule, which was expanded in scope under President Trump and repealed by President Joe Biden in January 2021. The gag rule also limits opportunities for NGOs to create partnerships with organisations that might provide or “promote” abortion, as USAID forces local agencies to sign refusals to provide or associate with anyone providing abortion services whenever the gag rule is reinstated. For such organisations, every change of administration in the USA thus means a renewed battle for funding, as well as a huge – and recurring – shift in their opportunities to secure funding, partnerships, and operational capacity.

Abortion rights remain a high-profile legal issue in Latin America and the Caribbean. Even if US pressure on NGOs operating in the region decreases under President Biden, European NGOs and development aid agencies are likely to face disruptions in their work with local partners as policy swings in the region continue.

Footnotes

References

Center for Reproductive Rights (1992–2021), World Abortion Laws Map, https://maps.reproductiverights.org/worldabortionlaws (28 May 2021).

Deutsche Welle (2021), CorteIDH aborda la criminalización del aborto en El Salvador (Inter-American Court of Human Rights Condemns the Criminalization of Abortion in El Salvador), 11 March, www.dw.com/es/corteidh-aborda-la-criminalización-del-aborto-en-el-salvador/a-56833283 (28 May 2021).

EuropaPress International (2018), Bolsonaro asegura que si gana las elecciones vetará cualquier intento de legalizar el aborto, (Bolsonaro Assures that if He Wins the Election, He Will Veto Any Attempt to Legalize Abortion), 13 October, www.europapress.es/internacional/noticia-bolsonaro-asegura-si-gana-elecciones-veta ra-cualquier-intento-legalizar-aborto-20181013040145.html (20 June 2021).

Feliciano, Omar (2017), Hacer olas por las mujeres: Women on Waves en Guatemala, (Making Waves for Women: Women on Waves in Guatemala), in: Animal Político, 7 March, www.animalpolitico.com/punto-gire/olas-las-mujeres-wom en-on-waves-guatemala/ (28 May 2021).

Ginella, Camila et al. (2017), A New Conservative Social Movement? Latin America’s Regional Strategies to Restrict Abortion Rights, Chr. Michelsen Institute, CMI Brief, 16, 5, 6: 1–5.

Human Rights Watch (2021), Dominican Republic: End Total Abortion Ban, 22 April, www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/22/dominican-republic-end-total-abortion-ban (28 May 2021).

Human Rights Watch (2017), Nicaragua: Abortion Ban Threatens Health and Lives, 31 July, www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/31/nicaragua-abortion-ban-threatens-health-and-lives (28 May 2021).

Marie Stopes International (2017), Re-Enactment of the Mexico City Policy, in: Reproductive Choices News, January, www.msichoices.org/news/2017/1/re-enactment-of-the-mexico-city-policy/# (28 May 2021).

Navarrete, Dirce, and Víctor Hugo Ramírez (2021), ¿Qué opinan las personas sobre el aborto en México? (What are People’s Opinions on Abortion in Mexico?), in: Animal Político, 13 January, www.animalpolitico.com/blog-invitado/que-opinan-las-personas-sobre-el-aborto-en-mexico/ (20 June 2021).

Olivares, Emir, Alma Muñoz, and Mirna Sevin (2007), Rechaza Carpizo impugnación de CNDH a la reforma sobre aborto (Carpizo Rejects Court Challenge by CNDH to Abortion Reform), in: La Jornada, 28 May, www.jornada.com.mx/2007/05/28/index.php?section=capital&article=038n1cap (20 June 2021).

Shah, Iqbal H., Elisabeth Ahman, and Nuriye Ortayli (2014), Access to Safe Abortion: Progress and Challenges since the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). ICPD Beyond 2014 Expert Meeting on Women’s Health, Background Paper 3, www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/Safe_Abortion.pdf (28 May 2021).

WHO (2012), Aborto sin Riesgos: Guía Técnica y de Políticas para Sistemas de Salud (Abortion Without Risks: Technical and Policy Guideline for Health Systems), Second Edition, www.paho.org/clap/dmdocuments/AbortoGuia2.pdf (28 May 2021).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Franco, Clara Yáñez (2021), Abortion Rights in Latin America: An Unsettled Battle, GIGA Focus Latin America, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-73978-0

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.