- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Dangerous Alliances: Populists and the Military

GIGA Focus Latin America

Dangerous Alliances: Populists and the Military

Number 1 | 2020 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Across Latin America, alliances between politicians and officers are again enabling the military to influence politics and policies. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has given a significant share of cabinet seats to current or former officers. While some have argued that soldiers may offer the incorruptible expertise needed for solving the region’s pressing problems, Latin America’s painful history suggests otherwise.

The military is once again stepping into the political arena. Soldiers have been granted greater operational autonomy, are being deployed internally, shielded from civil persecution, and again holding important cabinet and ministerial posts.

Although straight-out military regimes are unlikely to occur in the region any time soon, Latin America’s history offers a strong warning against the military’s expanding political role. Where soldiers gained political influence in the past, democratic institutions, civil liberties, and human rights came under pressure.

With the region’s structural problems of violence, corruption, and inequality unresolved, the demand for drastic solutions have intensified. Citizens and politicians alike see in officers the apolitical, incorruptible, and effective policymakers capable of solving the region’s most pressing problems.

The armed forces for their part have often gladly taken up the offer to enter the political arena. In search of purpose and orientation, assuming political roles promise the militaries new tasks, more resources, and the opportunity to restore lost prestige.

Policy Implications

The case of Brazil shows how swiftly soldiers can regain influence over political decisions in democracies. An increasing political role for the military seems likely across the region; with it, all the detrimental consequences for political opposition and civil society groups will ensue. Only if the political considerations of both government leaders and military decision makers change will it be possible to halt the militarisation of Latin American politics.

The Military’s Political Return

Across Latin America, the renewed influence of the military over politics can be witnessed. As protests spread across the region in the second half of 2019, presidents in Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador sent soldiers out onto the streets. Ecuador’s President Lenín Moreno and Chile’s President Sebastián Piñera appeared on television surrounded by soldiers dressed in military fatigues to declare states of emergency. Like in Bolivia and Colombia, the deployment of military forces triggered brutal crackdowns on social and political activists. What many thought impossible given Latin America’s painful past now seems palpable once more: Throughout the region, government leaders are seeking the political legitimacy and strength of the armed forces. The region, it seems, is on the brink of entering a new phase of political militarisation.

In various Latin American countries – including Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico – soldiers are currently undertaking police operations against criminal organisations and drug cartels. At the same time, troops have been equipped with more legal protection. Like the autocratic government of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, democratically elected governments in Brazil and Colombia has shifted jurisdiction for serious crimes committed by the armed forces from civilian to military courts. In Guatemala, former president Jimmy Morales, pressured by the military backers within his party, even ended the United Nations-sponsored International Commission against Impunity (CICIG) tasked with investigating human rights violations by the country’s security forces. In Bolivia, interim president Jeanine Áñez even gave soldiers carte blanche to crush domestic protests.

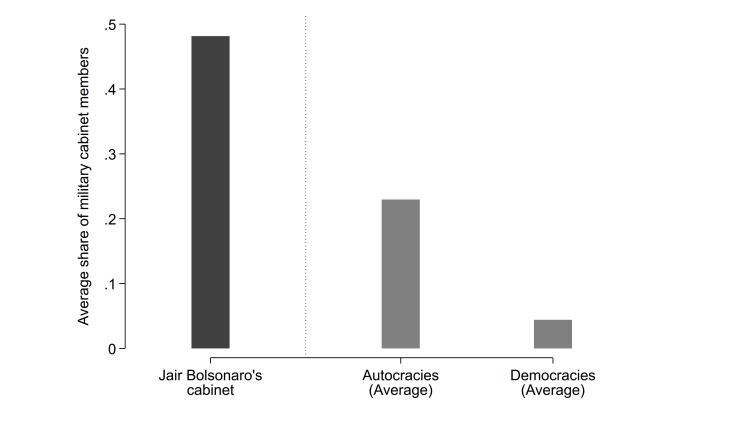

The internal use of the military hints at a deeper change taking place in Latin America: Across the region, officers are again gaining influence over politics and policies. In Bolivia, the armed forces played an important role in the resignation of President Evo Morales, which allowed conservative elites to augment their political power. The president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, recently stationed heavily armed soldiers and police officers inside the country's legislative assembly to pressure deputies into financing his security plan. In other countries, officers serve as ministers and secretaries, hold positions within government agencies, and advise presidents and political leaders. In Brazil, for example, individuals with military experience have occupied almost half of all cabinet seats since 2019, including President Jair Bolsonaro himself as well as retired army general and current vice president Hamilton Mourão (see Figure 1 above). When comparing these numbers to historical cabinets in both autocratic and democratic regimes, the unprecedented military dominance within Brazil’s current government is clearly visible. Brazil is no exception, either. In Guatemala, the Association of Military Veterans of Guatemala (AVEMILGUA) founded the party that brought Morales to power. Together with the country’s old civil–military elites, the association also played a critical role in advising the president to eventually abandon the CICIG.

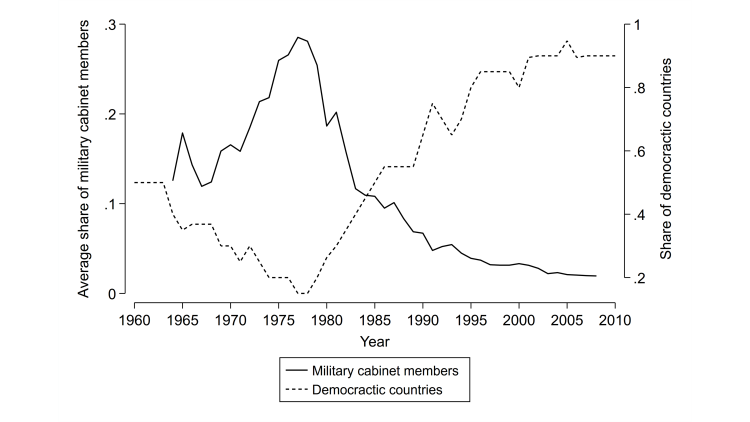

The developments in Brazil, El Salvador, and Guatemala are concerning. The mixing of political and military affairs recalls Latin America’s troubled past. During the 1960s and 1970s, cabinets were dominated by generals. Officers in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Guatemala ruled their countries with iron-fist policies that precluded serious attempts at democratic participation and accountability. The current developments are even more worrisome since most experts agree that keeping soldiers out of political affairs is a key feature of stable democracies. Over the last 30 years, Latin America’s drive towards democracy would be accompanied by a strong reduction of soldiers active in politics (Figure 2). Separating out civil and military matters, enhancing civilian oversight, and creating clear channels for command and control have been central aspects in the security sector reforms undertaken in the region (Pion-Berlin 2009). Only the autocratic regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela have given their armed forces a continuous say in politics. In these regimes, the political roles of soldiers are intended to protect leaders from coups, revolutions, or popular uprisings.

For the region’s democracies, the comparison with autocratic regimes highlights the risks of granting soldiers political influence. Involving the military in day-to-day partisan politics may re-politicise “an institution that Latin Americans spent the last generation collectively removing from politics” (Fisher 2019). A deeper look at Latin America’s history yields important lessons for better understanding the dangers of employing officers as cabinet members, ministry staff, or political advisers.

Lessons from Latin America’s Past

Recent news reports and op-eds indicate that some commentators are less concerned about the military’s political influence at least. For example, in Brazil the “military wing” has been described as the moderate faction within the Bolsonaro government. Three-star general Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz and Vice President Mourão have repeatedly been depicted as the more rational and pragmatic actors within the administration, balancing the radical president and his “ideological” (Casarões and Flemes 2019) or “conservative” (Stuenkel 2019) faction. Forgotten seems to be Mourão’s statement that a coup by Brazil’s armed forces may be justified in certain circumstances. Latin American history offers several examples of how the military’s influence over politics can have strong repercussions for democratic institutions and citizen rights. While full-blown military dictatorships are unlikely to occur any time soon, the region’s painful past shows that the soldiers’ political influence is often linked to authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights violations

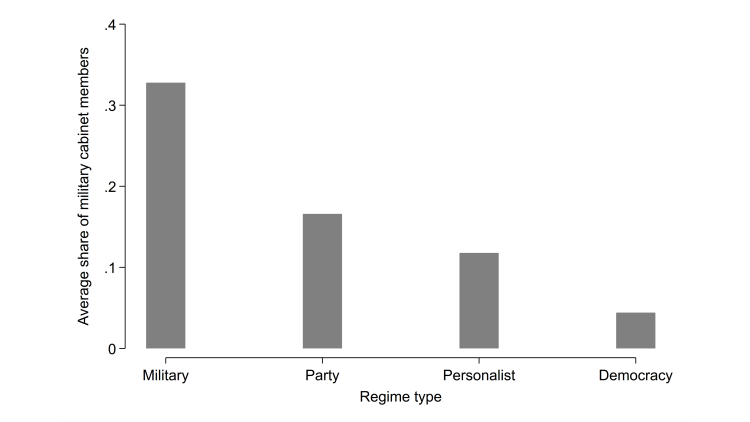

Historically, the involvement of soldiers in politics is a marked feature of autocratic regimes. Military dictatorships like the ones in Argentina (1976–1983) and Chile (1973–1989) had the highest average share of military cabinet members (Figure 3). After officers assumed power in such countries, which most did through coups, they commonly shut down channels of democratic participation. Free and fair elections became the exception, as the military considered itself superior to the questionable, volatile preferences of citizens and politicians. Similar thinking also dominated single-party regimes in Cuba or Mexico, as well as personalist regimes too – where political power was in the hands of individual leaders like Alberto Fujimori in Peru or Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. These regimes also featured comparatively high numbers of military personnel in government and allowed only scant political participation and accountability. In contrast democracies, which ensure the broad political participation of citizens through free and fair elections, historically featured the lowest participation of the armed forces in politics. And when officers held cabinet seats, they commonly served as defence ministers overseeing the armed forces. The political representation of the military was hereby often guaranteed by constitutions that were remnants of past autocratic regimes themselves (Albertus 2019). Before the generals retreated to the barracks, they made sure to preserve the military’s influence and shield themselves from reform or investigation.

Latin America’s history also shows how soldiers’ heightened political participation fostered corruption. Autocratic regimes and dictators usually included officers in cabinet to buy the loyalty of the armed forces. Like Maduro in Venezuela today, rulers used this form of co-optation to prevent soldiers from staging coups or defecting to the opposition. The military, on the other hand, regularly used their political weight to increase their involvement in the country’s economic sectors. Officers served as managers in state-owned companies or took up lucrative positions as board members. For soldiers, this generated abundant opportunities to enrich themselves, forging long-term nepotistic networks between economic and military elites like in Argentina (1976–1983) and Guatemala (1963–1986). The corruption incentivised economic mismanagement, fuelled the affected countries’ economic decline, and increased social inequality.

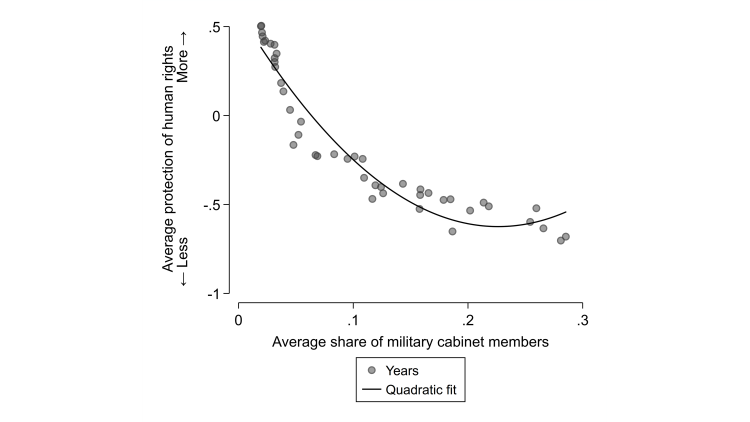

Finally, countries with a strong military dominance were also more likely to adopt iron-fist policies against political opponents and civil society at large. Historically, higher shares of military cabinet members correlate with the more widespread abuse of human rights (Figure 4). Military-dominated regimes frequently deployed military or paramilitary forces against internal opposition groups. Infuriated by political resistance, the security forces targeted whole segments of society in the hope of rooting out all forms of dissent. All too often, these heavy-handed operations resulted in gross violations of human rights. Regimes including the ones in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Uruguay illegally imprisoned, tortured, killed, and made disappear hundreds – in some cases even thousands – of individuals.

Taken together, in the course of Latin American history the military’s involvement in politics would often be accompanied by the suspension of elections and the erosion of democratic institutions. Where the military gained political weight, the economic sector was likely to suffer from mismanagement and corruption. Finally, military-dominated regimes ruthlessly cracked down on political opponents and civil society. As a result, citizens saw their civil liberties and their human rights violated on a massive scale. This begets the question of why we now again see alliances forming between politicians and military officers in the region. Why do Latin American citizens support politicians who make no secret of their plans to pull soldiers back into the political arena? And why are soldiers themselves keen to gain political influence once more?

Reasons for the Military’s Political Comeback

In the past, military officers assumed political roles through coups. Despite the notable exceptions of Ecuador (2000), Venezuela (2002), and Honduras (2009), illegal power grabs by the military have become rare in the region. Nowadays, democratically elected governments invite soldiers to step into the political arena. As Brazilian four-star general Augusto Heleno explained: “We are fully aware a coup is not the way forward. The path will be the next election” (Winter 2019). To make sense of this “consultative variant” (Mora and Fonseca 2019) of the military’s political involvement, it pays to look at Latin America’s unresolved structural problems and how they generate the motivation for politicians and soldiers alike to forge alliances.

Why Politicians Increase the Military’s Political Influence

Latin American countries have struggled with economic inequality, corruption, and weak democratic institutions for decades now. The election of left-leaning governments during the so-called pink tide of the first decade of the new century, which promised increased political and economic inclusion, generated high hopes for structural change. However the modest achievements of these governments, combined with persistent corruption scandals and low economic growth rates, have caused growing frustration among large segments of Latin American society. Social polarisation and class conflict still persist, feeding into a pervasive security problem (Kurtenbach 2019a). Events in Chile and Ecuador demonstrate how deep economic and political frustration run, and indeed how quickly they can destabilise a country.

In recent years, the desire for genuine improvement has led citizens to gravitate towards populist agendas (Ruth-Lovell 2019). For politicians eager to (re-)win elections, propagating simple but radical solutions to the region’s problems has become a viable political strategy. Politicians and government leaders like Jair Bolsonaro or Andrés Manuel López Obrador brand themselves as figures operating outside the realm of the corrupt political class, ones who understand the people’s problems – to which they offer real and simple solutions. To give credence to their image and political platforms, both political underdogs and ruling presidents have sought the political support of soldiers.

Despite its poor historical record as a governing institution, the military still enjoys high prestige throughout the Americas. In surveys the military consistently ranks among the most trusted institutions, while faith in elections, courts, or the police have declined year-on-year (Flores-Macías and Zarkin 2019; Mora and Fonseca 2019). Soldiers are considered to have integrity, be incorruptible, and to be equipped with the skills and determination to get the job done. Neither past nor current scandals – like, for example, the so-called Milicogate case in Chile where army offices enriched themselves with a comprehensive kickback scheme – seem to have affected this attitude. For most Latin American citizens, the military remains a moral authority. Politicians, in turn, hope to utilise the positive perception of the armed forces for their own political gain.

Political leaders increasingly rely on soldiers to formulate and implement policies. Leaning on the armed forces allows government leaders to bolster their own legitimacy and, if necessary, bypass democratic institutions. Recruiting officers as ministers, staff members, or political advisers is seen to demonstrate the political willingness and capability to address a country’s intractable problems head on. This process is particularly visible in the domain of internal security. While high crime numbers are one of the most pressing issues in Latin America, police forces – plagued as they are by corruption and a lack of trust among the community – have not been able to halt criminal and drug trafficking organisations. Mounting public pressure for results has led elected civilian governments to turn to the military, despite the dangers of empowering the armed forces with internal duties. In Mexico, President López Obrador – while highly critical of the armed forces at first – has tasked officers with the creation of a new, militarised national guard, despite clear evidence that such forces are detrimental to security and stability (Flores-Macías and Zarkin 2019).

For government leaders, there is a particularly strong incentive to benefit from the military’s robust standing in times of political crisis. When faced with mounting dissatisfaction from among the domestic population, leaders can draw on the military to signal that they have soldiers’ political backing. In Latin America, this has been exploited by those from across the political spectrum. Left-wing presidents in Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela placed officers at the cabinet table so as portray “themselves as leaders of a civil-military revolutionary vanguard beset by enemies foreign and domestic,” right-wing presidents in Brazil and Guatemala have used their militaries “as bulwarks of virtue and safety” (Fisher 2019). Throughout the region this has generated a political logic whereby, according to Aníbal Pérez-Liñán (Fisher 2019), political leaders who can count on the support of the armed forces know that they can defy political rivals as well as protesters in the streets, violate human rights, get away with corruption, and still remain in power – even beyond the presidential term limit set out in the constitution.

Why Soldiers Want to Influence Politics

In Brazil, soldiers have happily taken up the offer of President Bolsonaro to sit at the cabinet table. Latin America’s chequered history also helps us understand why militaries have again become willing to forge alliances with political figures. With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent decline of international and internal conflicts, democratic governments cut military budgets, scaled back the armed forces, and subjected soldiers to increased civilian oversight (Fisher 2019; Pion-Berlin 2009). Moreover, the atrocities of the 1970s stained and internally fractured most armed forces – leaving them within a crisis of meaning, and in fear of accountability. Since then, militaries have searched “for purpose; uncertain of their identity, their mission, and place in society” (Mora and Fonseca 2019). Latin American officers have sought ways to justify their professional value, salvage their reputation, and secure sufficient funding.

Being offered posts in cabinets or ministries promises the armed forces a way back to past glory. Generals have speculated that being involved in politics will demonstrate the virtue of a well-quipped military: a competent helper in times of crisis that stabilises the political arena, balances the radical notions of government leaders, and skilfully solves the country’s most pressing problems. It also promised protection from deeper political and judicial scrutiny. With past crimes by the military still remaining unresolved in many Latin American countries, generals have to fear that they will eventually face investigation and criminal persecution if they stay out of the political arena indefinitely. Against these expectations, taking up political roles offers a promising way to preserve the military’s standing while protecting it from far-reaching investigation and reform.

Overall, the interests of both political leaders and soldiers have generated strong motivation for both actors to forge pacts that expand the military’s role into politics. The drive for the greater political role of the armed forces carries, however, the danger that “[e]very cycle of crisis risks heightening perceptions of the military as a partisan institution and weakening taboos against its involvement” (Fisher 2019). This risk now seems more real than ever, after in December 2019 the Bolivian military successfully urged Morales to quit – potentially establishing a precedent for future military interventions in the region.

Slowing Down a New Phase of Militarisation

With comprehensive solutions to the region’s enduring structural problems currently not in sight, the military’s involvement in politics is likely to only persist. Despite this projection, the preceding analysis offers several implications for how a new phase of full militarisation in Latin America may at least be slowed down. First, a strong motivator for officers to move into politics is the protection of the military organisation and their own economic well-being. This implies that soldiers will be less likely to adopt political roles if they know that their organisation is well funded, their careers are not at risk, and their promotions are free from political interference. Securing such benefits may reduce soldiers’ willingness to step into the political arena, and could generate political leverage to confine the armed forces to their original role.

Second, another potential way to curb the military’s influence is to raise awareness about the dangers of taking up political roles within the armed forces themselves. Professional military training has an important role to play here. It may reduce the long-term incentives of soldiers to meddle in civilian affairs if it couples military professionalism with the virtues of civilian oversight and inculcates officers with democratic norms. To this end, training needs to be more contextualised (Agüero 2019). It must clearly transmit the historical repercussions of military rule not only for states and citizens, but also for military organisations themselves. International partners may support such depoliticisation efforts by providing foreign training programmes that are geared towards this goal.

Furthermore, with the military deployed on the streets in several Latin American countries, expanding military training on citizens’ civil liberties and human rights seems equally paramount. Both domestic and foreign-sponsored training programmes commonly include such topics. Yet in practice, content often rests on the discussion of general and abstract normative concepts while avoiding clear links to the military’ own history (Agüero 2019). Teaching historical and contemporary developments can help in educating particularly those officers who did not experience the dictatorships of the past, and therefore may be overly optimistic about the military’s enhanced role.

Finally, analysis suggests that a further militarisation of the region is unlikely to be prevented unless the incentive structures for government leaders are changed. Given the severity of Latin America’s political and economic problems, this only seems feasible in the long run. In the past, international constraints – for example under the Inter-American Democratic Charter of the Organization of American States – have helped to protect democracies from military interference (Mora and Fonseca 2019). This requires vigilance on the part of the international community and, if necessary, the willingness to build up coordinated diplomatic pressure both within the Americas as well as between the United States and Europe.

However, the chances for such concerted responses currently seem slim. The crisis in Venezuela has deepened the political rifts within the Organization of American States (Kurtenbach 2019b). The US as one of the most important actors in the region, currently lacks both the political credibility and indeed the will to halt the military’s heightened political influence in allied countries. And with China and the US competing for global economic influence, Europe’s opportunities to initiate a rethink among Latin American government leaders remain limited at best. Together this suggests that a further militarisation of Latin American politics will be difficult to curb from the outside. As long as the region’s structural problems of economic inequality, weak institutions, corruption, and insecurity remain unresolved, the motivation of governments and militaries to include more soldiers in politics is likely to prevail.

Footnotes

References

Agüero, Felip (2019), After Chile, It’s Clear Militaries Evolved Less Than We Thought, in: Americas Quarterly, 17 December, www.americasquarterly.org/content/evolution-latin-americas-armed-forces (9 January 2020).

Albertus, Michael (2019), The Fate of Former Authoritarian Elites Under Democracy, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63, 3, 727-759.

Casarões, Guilherme, and Daniel Flemes (2019), Brazil First, Climate Last: Bolsonaro’s Foreign Policy, GIGA Focus Latin America, 05, September, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/brazil-first-climate-last-bolsonaros-foreign-policy (22 January 2020).

Fariss, Christopher J. (2019), Yes, Human Rights Practices Are Improving Over Time, in: American Political Science Review, 113, 3, 868-881.

Fisher, Max (2019), "A Very Dangerous Game": In Latin America, Embattled Leaders Lean on Generals, in: New York Times, 31 October, www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/world/americas/latin-america-protest-military.html (9 January 2020).

Flores-Macías, Gustavo A., and Jessica Zarkin (2019), The Militarization of Law Enforcement: Evidence from Latin America, in: Perspectives on Politics, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719003906.

Geddes, Barbara, Erica Frantz, and Joseph G. Wright (2018), How Dictatorships Work: Power, Personalization, and Collapse, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kurtenbach, Sabine (2019a), The Limits of Peace in Latin America, in: Peacebuilding, 7, 3, 283-296.

Kurtenbach, Sabine (2019b), Latin America – Multilateralism without Multilateral Values, GIGA Focus Latin America, 07, December, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/latin-america-multilateralism-without-multilateral-values (22 January 2020).

Mora, Frank, and Brian Fonseca (2019), It’s Not the 1970s Again for Latin America’s Militaries. Here’s Why, in: Americas Quarterly, 17 December, www.americasquarterly.org/content/new-role-latin-americas-militaries (9 January 2020).

Pion-Berlin, David (2009), Defense Organization and Civil–Military Relations in Latin America, in: Armed Forces & Society, 35, 3, 562-586.

Ruth-Lovell, Saskia P. (2019), The Side Effects of Courting the People–Populists and Liberal Democracy, Focus Latin America, 03, May, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/the-side-effects-of-courting-the-people-populists-and-liberal-democracy (14 January 2020).

Stuenkel, Oliver (2019), How Bolsonaro’s Rivalry with His Vice President Is Shaping Brazilian Politics, in: Americas Quarterly, 18 April, www.americasquarterly.org/content/how-bolsonaros-rivalry-his-vice-president-shaping-brazilian-politics (9 January 2020).

Winter, Brian (2019), “It’s Complicated”: Inside Bolsonaro’s Relationship with Brazil’s Military, in: Americas Quarterly, 17 December, www.americasquarterly.org/its-complicated-bolsonaro-military (9 January 2020).

White, Peter B. (2017), Crises and Crisis Generations: The Long-term Impact of International Crises on Military Political Participation, in: Security Studies, 26, 4, 575-605.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Scharpf, Adam (2020), Dangerous Alliances: Populists and the Military, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-66812-6

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.