- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The New Turkey and its Nascent Security Regime

GIGA Focus Middle East

The New Turkey and its Nascent Security Regime

Number 6 | 2020 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Much attention has been paid to the ongoing Islamisation under AKP rule in Turkey. Yet while President Tayyip Erdoğan nowadays relies more on coercion, the focus on the aforementioned ideological transformation overlooks the key relevance of the new security regime now dominating Turkish politics. Efforts to establish the New Turkey have culminated in the politicisation of the military and the militarisation of politics.

Erdoğan backtracked on the European Union’s proposed path of establishing “objective control of the military” in legal-institutional terms and opted instead for its “subjective control,” specifically by fusing together the civilian and military spheres and politicising the latter.

Along with a highly militarist discourse, Erdoğan is diversifying the country’s military and paramilitary instruments in both domestic and foreign politics as a strategy of coup-proofing and regime survival.

The nascent security regime is not without its defects. Beside fractures within the ruling coalition that might endanger loyalty to Erdoğan, the effect of paramilitarisation on coup-proofing is open to question.

Policy Implications

European Union authorities need to build a more comprehensive approach that covers such a diverse array of armed organisations, and considers the militarisation of domestic and foreign politics together. They should be in political dialogue with the Turkish state for a full-fledged civilianisation of the regime along the Copenhagen criteria.

Attempts to read Turkey’s authoritarian turn predominantly focus on the top-down Islamisation of state and society during the last two decades under the rule of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP). However, the overemphasis on the aforementioned ideological transformation overlooks what the limits of this self-admittedly non-achieving social and political engineering project are. The Turkish youth is gradually distancing itself from religion, illustrating an organic, bottom-up secularisation. Likewise, President Tayyip Erdoğan long lost his narrative to win the hearts and minds of society, making him rely less on consent and more on coercion. More importantly, the overwhelming ideational readings of AKP politics fail to notice another dimension of Turkey’s ongoing transformation: the emerging security regime enhancing the state’s coercive capacity in all facets of domestic and foreign politics.

Erdoğan is a true survivor. He faced successive Kemalist offensives such as the military’s 2007 e-memorandum and the 2008 AKP’s closure trial at the Constitutional Court. Then, in 2013, the massive anti-government Gezi Protests and the corruption probe against his entourage posed serious challenges to his rule. Erdoğan nonetheless pulled through each time, even though any single one of these events would have been enough to depose a political leader in Turkey’s past. Lastly, the 15 July 2016 failed coup attempt, for which Ankara blames the religious leader Fethullah Gülen and his followers, contrariwise granted him the most extensive powers any Turkish leader has ever had. Institutionalised by Turkey’s 2018 transition to a hyper-presidential system, the survival of his nascent autocracy amidst economic slumps, political tensions, and diplomatic crises required him to pull all the strings at his disposal. Especially since the 2016 coup attempt, Erdoğan has sought, on the one hand, to maintain political control by purging the military and counterbalancing it via a network of paramilitary forces. On the other, buttressing his confrontational rhetoric, he has increasingly relied on hard power to mobilise the masses and suppress dissent at home while gaining diplomatic leverage abroad too. All these have ultimately led to the politicisation of the military and the militarisation of politics in Turkey.

Politicisation of the Military

Non-democratic leaders reasonably fear their armies. A recent study covering the years 1946 to 2010 shows that military coups, though in decline, are the most common way of overthrowing them (Geddes et al. 2018: 179). Moreover, the costs are higher than losing office merely. According to another study, only 20 per cent of ousted leaders escape post-tenure punishment such as murder, imprisonment, or exile (Goemans et al. 2009). Fears must be more grounded in a country where the army has the habit of intervening in politics almost every decade (in 1960, 1971, 1980, 1997, 2007, and 2016), albeit in different forms. Non-democratic leaders, therefore, heavily invest in coup-proofing measures ranging from establishing personal loyalty among officers on ethnic, religious, ideological, and/or material grounds to building up armed forces parallel to the regular military.

Based on mutual suspicions, AKP in its initial years proceeded quite cautiously and held onto power mainly by leveraging Turkey’s European Union candidacy – which, along with the acquis communautaire, obliged the country to curb the military’s political prerogatives. One of the popular terms of this period was “the military tutelage” (askeri vesayet), which the AKP elite kept targeting in their speeches as a defining practice of “Old Turkey” and a dark force clouding the national will. The legal amendments legitimised by the EU conditionality reached their apex during the 2010 constitutional referendum, which allowed the trial of military officers in civilian courts should they commit crimes against the state. Such reforms aimed to institutionalise the “objective control of the military” in Huntingtonian terms, resting on the clear separation of the civilian and military spheres and coming along together with civilian-oversight mechanisms and military professionalism. Yet, Erdoğan gradually opted for the more typical path taken in the Middle East – that is, the “subjective control of the military” that anticipates a balanced fusion of both spheres. Yet in practice, it mostly involves politicising the military in the mirror image of the incumbent(s). That was a clear deviation not only from the EU’s proposed path, but also from Old Turkey practices. Be it directly or indirectly, the Turkish military intervened in politics regularly; however, it did not aim to fully dismantle the multiparty politics or attain the executive post definitively. Instead, it paid utmost attention to protecting its “above politics” image, acting in unison as the self-appointed guardian of the state. To now ensure his form of civilian control, Erdoğan: a) purged non-loyal officers in the military; b) tried to staff it with loyalists; and, c) reshuffled the military structure to ensure his own supremacy.

In every August, dismissals from the army for reasons of “reactionary” [read “Islamist”] activities used to be the default agenda of the Supreme Military Council (Yüksek Askeri Şura, YAŞ) meetings in Old Turkey. After the 1997 intervention, the military intensified its efforts to cleanse religious elements and gain a more homogeneous secular structure. Yet, none of these purges could be compared to the overhauls within the army during the AKP era. Based on a series of trials, most prominently the 2008 Ergenekon and 2010 Sledgehammer cases, the first wave of purges targeted the Eurasianists in the army and sent hundreds of both retired and active-duty officers to jail for plotting to topple the AKP government (Taş 2014). It came out that what was at the time celebrated as a fatal blow to the Turkish “deep state” did not aim much higher than playing with the internal line of promotions and at the fast-tracking of loyal/Gülenist officers. From the August 2010 YAŞ meeting onwards, AKP managed to impose its own list of promotions and retirements, while vetoing the promotions of the officers affiliated with the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases. The growing rift between AKP and the Gülenists culminated in the 2016 abortive coup and the second, ongoing wave of purges. Some 149 generals and admirals out of 325 in total were purged by a statutory decree on 20 July 2016 over alleged Gülen links, whereas more than 20,000 military personnel have since been expelled.

When the post-coup purges significantly reduced the ranks of the military, this created a golden opportunity for Erdogan to reshape the institution in his own self-image. Some 51,144 new personnel had been recruited to the military by 2019. Loyalty appears to be the main criterion for promotion. The forced retirement of Generals Metin Temel and Zekai Aksakallı, or the denial of promotion for Cihat Yaycı – who all played an important role in the suppression of the 2016 abortive coup or in the subsequent Gülenist purge – show that ideological loyalty is not enough; personal loyalty (to both Erdoğan and Defence Minister Hulusi Akar) is also necessary. Erdoğan’s long-term ambition for the army is also evident in the closure of all existing military academies, assumed to be castles of Kemalist indoctrination, and in the establishment of a National Defence University as an umbrella body for military education.

Amidst purges, forced retirements, and promotions, Erdoğan has tightened his grip over the military by certain institutional manoeuvres to diminish its autonomy. Successive statutory decrees have heavily restricted the chief of general staff’s duties and powers, while the Land, Naval, and Air Force Commands are subordinated to the minister of national defence. The president has now the authority to nominate the service commanders, receive information from, and give direct orders to them. Furthermore, the number of civilian members in YAŞ has also been increased to strengthen civilian control (Akça 2018).

The micro-engineering of the army by the AKP elite has harmed the spirit de corps along with also leading to increasing politicisation across military ranks. Overriding professional norms and meritocratic promotion based on competence and seniority, officers’ career trajectories have increasingly been aligned to favourable ties to the political leadership. It is now commonplace to see the photos of middle- and high-ranking officers in AKP’s events and local offices. Despite the growing image of the army as the party’s branch, one may still find it difficult to call the Turkish army Erdoğan’s army. The split between the (pro–North Atlantic Treaty Organization) Atlanticists and (anti-Western) Eurasianists among the higher echelons of NATO’s second-biggest army is not a new one. Since 2014, Erdoğan has recruited several high-ranking officers convicted in the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials to buttress the anti-Gülenist front in the military, but now he is again quietly eliminating them from YAŞ promotions. Erdoğan still does not enjoy a loyal base of human capital, especially among the higher military ranks. In fact, the whole system is contingently based on the mutual trust between Erdoğan and Akar and the latter’s career as the former chief of general staff (Gürcan 2020). Again, whether the working relationship between Akar and the current chief of general staff, Yaşar Güler, can be sustained between their heirs is another question.

The Militarisation of Politics: New Turkey in Arms

Unlike his anti-militarist agenda in the early years, civilianisation is not a major concern of the Turkish president. From the suppression of the Kurds in southeast Anatolia to foreign military interventions, Ankara has increasingly resorted to coercive power. While investment in military power in a war-torn, fragile region reflects a rational calculation, the ruling AKP elite has deliberately adopted the militarisation of domestic and foreign politics as a strategy to consolidate the regime.

Militarisation in Turkey can be traced both horizontally (across policy spaces) and vertically (multiplication of armed instruments). Horizontal militarisation, the growing reliance on military and militarist language in both domestic and foreign politics, rests on a populist framing of politics as Turkey’s “Second Liberation War” against the Western imperialist elite and their domestic collaborators. At home, it helps Erdoğan consolidate his mass support and deter opposition. While any challenge (from the depreciation of the Turkish lira to women’s rights) has become cast as part of a larger conspiracy, the militarist liberation war rhetoric makes any social or economic problem only secondary to the “survival of the nation” (milletin bekasi).

Moreover, the country’s interventions in Syria, Libya, and Azerbaijan, along with a “boots on the ground” narrative, have increased Erdoğan’s popularity and fanned nationalistic sentiment, surpassing the traditional AKP base and consolidating his de facto coalition with the ultra-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP). Sustaining a vigilant civilian support base and keeping the army busy abroad are also significant strategies for coup-proofing. Above all, without undermining his pragmatism and U-turns in the past, militarisation might be the only thing left at Erdoğan’s disposal since the normalisation of politics and rule of law appear much less likely prospects for the future. Again, hard power is Erdoğan’s sole leverage to dictate terms internationally, given the country’s increasing isolation in the Middle East and North Africa.

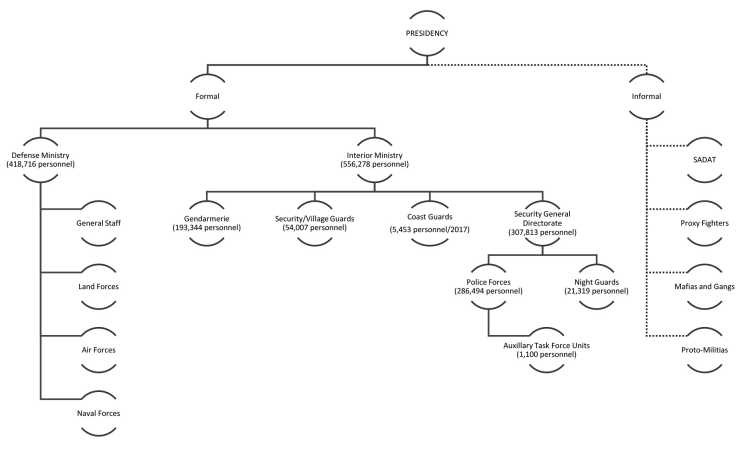

As for vertical militarisation, Turkey has witnessed either the increasing paramilitarisation of the existing security forces with stronger ties to the office of the president or the establishment of multiple new layers of paramilitary forces. In the new structure, the Interior Ministry commands as large an armed force as the regular military does. These include the gendarmerie, the security guards, the police forces, the night guards, and the coast guard. Then, another layer of paramilitary forces (including, but not limited to, SADAT, proxy fighters, mafia, and proto-militias) is informally linked to the regime in order to insulate Erdoğan from military threats and to diversify his coercive instruments.

a) Armed units under the Interior Ministry

Gendarmerie: Turkey’s paramilitary police force, the Gendarmerie, together with the Coast Guard Command, was subjugated to the Ministry of the Interior, limiting its ties to the military to times of military mobilisation. Last year, it also signed a memorandum of understanding with the Russian National Guard, Rosgvardiya, in the fields of public security, protection of state facilities, and combatting extremism.

The Security (Village) Guards: Originally set up in 1985 as a temporary measure to protect Eastern villages and to aid the military, the village guard system has gradually been integrated into the security structure. Their name was changed from village guards to security guards, their work field was extended beyond villages – with the right to possess and carry personal arms. The government retired in 2017 more than 18,000 village guards and recruited over 25,000 new guards to rejuvenate the ranks.

The Police: The paramilitarisation of the police forces with military-grade equipment and extensive authority to suppress urban dissent gained momentum after the 2013 Gezi Protests and was materialised by the 2015 Domestic Security Reform Package (İç Güvenlik Paketi). A new, mobile law enforcement unit called the Auxiliary Task Force Police Unit (Takviye Hazır Kuvvet Polis Birimi) was instituted with branches in Ankara (2018) and Istanbul (2020) to protect Erdoğan.

The Night Guards: In 2016, Erdoğan re-established the old practice of neighbourhood watch abandoned in 2008 again under AKP rule. With a legal amendment in 2020, the now 21,000-strong network of night guards is also granted extensive powers to carry out identification checks, body checks, search cars, and to use lethal force if needed.

b) Forces outside the formal security structure

SADAT: Adnan Tanriverdi, a former one-star general dismissed in 1996 over Islamist links, established in 2012 – in the midst of the Arab uprisings – SADAT International Defense Consulting – a private firm providing training on irregular warfare. He was appointed as Erdoğan’s chief security advisor after the 2016 abortive coup, but resigned after his apocalyptic public statement in December 2019 that their struggle was all to pave the way for the imminent arrival of the awaited Mahdi – a Messianic figure in Islam. Several observers and media reports say that Ankara “outsourced” some paramilitary activities – such as the recruiting, training, logistics, and transfer affairs of militias – in Libya and Syria to SADAT, which has continued to completely deny such allegations (Eissenstat 2017).

Proxy fighters: Based on a 2015 agreement signed with the United States, Turkey hosted several militia groups as part of the train-and-equip programme for moderate opposition Syrians. The use of proxy forces in Turkey’s foreign interventions was taken to another level, however, when Erdoğan acknowledged the presence of Syrian mercenaries alongside the Turkish army in its Libya operations. Similarly, despite Ankara’s denial, international media reports indicate that Turkey has been deploying Syrian mercenaries to support Azerbaijan in its recently renewed fighting with Armenia over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh area. This trend resonates with SADAT founder Tanrıverdi’s 2019 statement that Turkey needs to establish a mercenary company like Blackwater (used by the US in Iraq after 2003) or Wagner (used by Russia in Syria and Libya since 2015) for operations abroad. In domestic politics, the Esedullah Team – a special forces unit that appeared during the 2015 urban conflict in Turkey’s predominantly Kurdish southeast and which was responsible for several human rights violations and killings at the time – allegedly included al-Nusra members.

Mafia and Gangs: The Turkish (deep) state’s relations with mafias and gangs are quite old. However, what used to be conducted in covert operations has now been performed openly, somewhat as the usual order of things. While the general disregard for the rule of law and the systemic overhaul of the security forces provided fertile ground for mafias and mobs to flourish, some leading mafia leaders like Sedat Peker have organised rallies to support the AKP–MHP coalition in general and presidential elections. A transnational example of these collusive practices is the close links between AKP deputy Metin Külünk and a violent gang, Osmanen Germania, which, according to the German media, was responsible for several acts of deterrence targeting dissidents abroad (ZDF 2017).

Pro-government proto-militias: Alarmed by the Islamist threat under AKP, 2007 saw the sudden mushrooming of several organisations, usually under the banner of National Forces (Kuvayi Milliye), to save Turkish independence from the Western imperialists and their collaborators – namely, AKP (Cevik and Tas 2013). A decade later, another wave of vigilant mobilisation came to prominence exactly with the same militarist discourse, yet now supporting AKP in its “Independence War.” From the People’s Special Operations (Halk Özel Harekatı), with members in armed camouflage patrolling the streets with vehicles resembling police cars in the aftermath of the 2016 abortive coup, to the Ottoman Hearths (Osmanlı Ocakları), known for mob attacks against journalists or branches of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP), these organisations showed their determination – and that they were willing to forfeit their lives for the chief, Erdoğan. Beside their militarist discourse exalting martyrdom, media reports indicated some of their leaders and members received training and fought in Syria.

The government also laid out the legal framework for the new security regime. First, on 14 July 2016, the day before the abortive coup, Erdoğan promulgated Law No. 6722 granting to the security forces blanket impunity for any damage and right violations perpetrated during the curfew. Largely considered as the reintroduction of the EMASYA protocol (The Protocol on Security, Public Order and Assistance Units), this assigns the military not only a legal shield, but also a commanding position over all the security forces in the war on terror so as to re-establish public order in the country. Second, Article 37 of Law No. 6755, dated 8 November 2016, exempts state employees from any legal or administrative responsibility for their decisions taken to suppress the 2016 coup attempt and terror incidents in its aftermath. With a broad and vague stipulation of terrorism that might cover any kind of dissent in Turkey’s present political context, this decree lifts criminal liability for all state employees open-endedly. Third, Article 121 of Decree No. 696, dated 24 December 2017, broadened the same sweeping immunity, again without a limited time frame, to civilians who were involved in the suppression of the coup attempt and of ensuing acts of terrorism. By these legal amendments, the government not only allows but also indeed encourages official initiatives, the formation of militia groups, and individual armament alike for the survival of the regime.

New Turkey’s security regime is still a work in progress (see Figure 2 below). Whether there is a master plan is unknown; however, the transitivity among such diverse formations (e.g. Syrian militants getting Turkish citizenship and position in the Turkish army, members of pro-AKP organisations fighting in Syria, mafia figures showing off in AKP local branches) is fairly intriguing. Again the collusion between multiple different forces as partners-in-crime reminds us that none of these elements should be considered in separation. For instance, the case of Ahmet Kurtuluş, former deputy-head of AKP’s Izmir branch, who was shot dead on 31 May 2019 in his residence provoked debate about a local organised crime network encompassing AKP politicians, mafia groups, the judiciary, intelligence, and the security forces. The alleged network blackmailed business people for money to clear their names from any Gülen-linked investigations and was also involved in a plan to murder the American pastor Andrew Brunson (McKay 2020).

Turkey’s Military and Paramilitary Juggernaut: Objectives and Threats

By transforming Turkey’s security structure and diversifying his instruments, Erdoğan primarily aims to respond to possible elite and popular threats that might include another coup attempt to overthrow him, an anti-government popular upheaval like the Gezi Protests (after ever-increasing pressures on secular lifestyle, or in case Erdoğan loses elections and does not relinquish power), and a civil war linked to Kurdish insurgency. Formal or informal, the paramilitary organisations will be handy to coordinate popular resistance against any attempt to overthrow Erdoğan. In fact, even the credible threat of using such forces against opponents is quite the deterrence against any upcoming wave of new Gezi Protests. Nevertheless, the government still reacts quite harshly against any kind of public demonstrations (be they on women’s rights or environmental issues) that might trigger broader street mobilisations.

Beside the multiplicity of armed formations, by its behaviour AKP also reveals a deliberate intention and effort to organise and arm its broader base, preparing it for a worst-case scenario. Each day, another news item (e.g. Diyanet’s 2016 circular for the formation of youth branches to be associated with the country’s 45,000 mosques, or the recent public debate about the proliferation of armed Salafi associations in Turkey) signals that societal militarisation goes beyond chants or the extensive appeal of popular Turkish historical television series like The Resurrection (Diriliş). While a large number of military-grade weapons and ammunitions distributed to pro-government vigilantes during the night of the 15 July 2016 abortive coup went missing, many regime supporters later shared photos of themselves on social media, posing with MP5 machine guns, for instance, and declaring their readiness to use weapons against the enemies of the nation. A pro-government writer, Sevda Noyan, recently said in a TV show: “Our family can carry off 50 people. We are very well equipped, materially and spiritually. We stand by our leader and will never forgo him. They [the secular opposition] should watch their steps. There are still several of them in our condo. My list is ready” (Gürsel 2020). Besides, Statutory Decree No. 676 also lifted restrictions on individuals who had been constrained from purchasing and possessing guns. According to the Umut Foundation, there are currently more than 20 million guns in Turkey and 90 per cent are not registered. These all make sense within the larger militarist discourse of Erdoğan, who sees “every young man as a potential commando candidate” to protect the nation.

It is not all about mere coup-proofing, for sure. The collusion with paramilitary organisations allows the regime to conduct irregular activities that may not be possible within the formal military structure (Cubukcu 2018). Moreover, Erdoğan needs this coercive power to establish the new regime in his own self-image. The night guards, acting like the moral police and exerting control over the public, illustrate this trend.

The construction of a new security regime does not eliminate certain threats for Erdoğan, who is walking through a political minefield. A first question is of maintaining loyalty. Erdoğan either needs to keep the ideological bonds alive or sustain a level of economic power able to ensure the continued distribution of material incentives for his supporters; on both grounds, his regime is shakier than ever. In addition, feeling threatened by rival power-elite groups, the personalisation of the regime was indeed a survival strategy for the Turkish leader in order to share power with as small a group as possible. Nevertheless, the lack of human capital in bureaucracy and diminishing shares of the vote in elections have pushed Erdoğan to make formal and informal coalitions with both left- and right-wing ultranationalists, who enjoy the spoils of incumbency more than ever. This marriage of convenience between distrustful partners has paved the way for the (re-)emergence of alternative centres of power. The rise of anti-Erdoğan mafia leader Alaattin Çakıcı, supported by MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli, and a recent viral photo of him together with other figures of Turkey’s old deep state such as former police chief and former interior minister Mehmet Ağar, former general Engin Alan, and former colonel Korkut Eken illuminates this possible fracture in the ruling power coalition.

A second question is if coup-proofing really works. According to recent studies, such strategies – most prominently counterbalancing the military with other security forces – are only partially successful, and the general coup risk remains in the absence of the regular succession of incumbents (Albrecht 2015). On the contrary, the introduction of paramilitary forces may increase the risk of coups in backlash (De Bruin 2018). The AKP government enjoys bringing up the issue of a possible Kemalist military intervention regularly, in order to solidify its conservative base and keep the anti-Kemalist victim discourse alive. However, by repetitive reminders keeping that possible threat on the table and attributing tangible power to the Kemalist forces, the government puts flesh onto this assumption, normalises it, and familiarises the public with such a potential future scenario.

Amidst sensational moves like the reconversion of the Hagia Sophia to a mosque, a more profound dimension of Turkey’s transformation is obscured. New Turkey rests on a wide network of diverse military and paramilitary organisations. EU authorities have so far focused on the democratic control of the armed forces by institutional means. The European Commission’s “Turkey 2020 Report,” for instance, examines the legal and institutional frameworks governing the security and intelligence forces, without taking notice of the larger trend of paramilitarisation. However, this formal approach neglects not only the current functioning of politics without constitutional constraints but also the both political and informal dimensions of civil–military relations. Likewise, the end result in the Turkish case illuminates the limits of the overarching EU model in its promotion of civilian control (Cizre 2004). Especially in light of current developments towards the increasing militarisation of Turkish politics, EU authorities should develop a more comprehensive framework that extends beyond a formal, institutional approach and takes the specificities of the candidate countries into consideration. Moreover, in EU “Progress Reports,” militarisation in Turkish domestic politics is still debated only as a local affair in relation to the urban conflict in the Kurdish-dominated southeast. Yet a more comprehensive approach should include the broader armament of society, along with the diversification in military and paramilitary formations. Finally, despite the EU’s close attention to Turkey’s use of hard power in its assertive foreign politics, it must be understood that militarisation in domestic and foreign politics complement each other and hence should be considered together. Not only the same populist militarist rhetoric but also the same instruments and strategies play a role in the formulation and implementation of these two policy fields.

Old or new, Turkey needs the EU both politically and economically; this grants the latter substantial leverage over the former. The EU also needs a stable, normalised Turkey for its own security. While EU leaders’ public criticisms only fan anti-Western sentiment in Turkey and give substance to the AKP’s populist rhetoric, bilateral political and bureaucratic channels need to be established or reinvigorated to reach the desired effects.

Footnotes

References

Akça, İsmet (2018), The Restructuring of Civil-Military Relations during the AKP Period, in: Confluences Méditerranée, 107, 4, 59–71.

Albrecht, Holger (2015), The Myth of Coup-Proofing: Risk and Instances of Military Coups d’état in the Middle East and North Africa, 1950–2013, in: Armed Forces & Society, 41, 4, 659–687.

Cevik, Salim, and Hakki Tas (2013), In Between Democracy and Secularism: The Case of Turkish Civil Society, in: Middle East Critique, 22, 2, 129–147.

Cizre, Umit (2004), Problems of Democratic Governance of Civil-military Relations in Turkey and the European Union Enlargement Zone, in: European Journal of Political Research, 43, 107–125.

Cubukcu, Suat (2018), The Rise of Paramilitary Groups in Turkey, in: Small Wars Journal, 3, March, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/rise-paramilitary-groups-turkey (3 November 2020).

De Bruin, Erica (2018), Preventing Coups d’état: How Counterbalancing Works, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62, 7, 1433–1458.

Eissenstat, Howard (2017), Uneasy Rests the Crown: Erdoğan and ‘Revolutionary Security’ In Turkey, POMED Snapshot, 20 December, https://pomed.org/pomed-snapshot-uneasy-rests-the-crown-erdogan-and-revolutionary-security-in-turkey/ (3 November 2020).

Geddes, Barbara, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz (2018), How Dictatorships Work, Cambridge: CUP.

Goemans, Henk E., Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, and Giacomo Chiozza (2009), Introducing Archigos: A Dataset of Political Leaders, in: Journal of Peace Research, 46, 2, 269–283, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343308100719 (3 November 2020).

Gürcan, Metin (2020), Erdoğan’s Ties with Turkish Army Gets Alarmingly Personal, Al-Monitor, 13 January, www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/01/turkey-erdogan-ties-with-army-become-increasingly-personal.html (5 November 2020).

Gürsel, Kadri (2020), Is a Coup Really Looming in Turkey?, Al-Monitor, 13 May, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/05/turkey-coronavirus-akp-reignites-coup-talk-economy-worsens.html (5 November 2020).

McKay, Hollie (2020), Jailed Turkish Mob Boss Claims Government Officials Dispatched Him to Kill American Pastor Andrew Brunson, Fox News, 1 September, www.foxnews.com/world/jailed-turkish-mob-boss-claims-government-officials-dispatched-him-to-kill-american-pastor-andrew-brunson (5 November 2020).

Mutschler, Max M., and Marius Bales (2020), Global Militarisation Index 2019, Bonn: Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC), https://gmi.bicc.de/in%20dex.php?page=ranking-table (5 November 2020).

Taş, Hakkı (2014), On the Illegitimate Use of Force: The Neo-Jacobins of Europe, in: The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms, 19, 5, 556–567.

ZDF (2017), Vertrauter Erdoğans zündelt in Deutschland, 12 December, www.zdf.de/politik/frontal-21/osmanen-germania-104.html (5 November 2020).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Taş, Hakkı (2020), The New Turkey and its Nascent Security Regime, GIGA Focus Middle East, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-70612-3

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.