- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Gender Justice as an International Objective: India in the G20

GIGA Focus Asia

Gender Justice as an International Objective: India in the G20

Number 3 | 2017 | ISSN: 1862-359X

The G20 states have made a commitment to drastically lower the gender differential in their labour markets. All G20 states, including India, will have great difficulty doing so, as the disparity is a consequence not of formal deficiencies, but of informal norms and value attitudes. It will take both time and holistic approaches on the domestic and international levels to change this.

Gender justice will feature more prominently at this year’s G20 summit under the German presidency. At past summits, the issue was rather neglected. The 2014 Brisbane Declaration represented a watershed moment, as the G20 states committed to reduce the gender gap in the labour market participation rate by 25 per cent by the year 2025.

Women’s employment rates in some countries are, however, stagnating – in India they have even dropped. Neither economic growth nor statutory requirements or strides in women’s education have improved the situation. Given all this, the question arises of how the stated objective can be reached.

The Modi government has developed a new strategy to increase women’s participation in the labour market that includes attracting textile and other manufacturing industries and promoting self-employment and professional qualifications.

It remains to be seen whether the measures will succeed; whether low-paying jobs in the textile industry will truly lead to good jobs; and whether this will increase women’s levels of societal, political, and economic participation. A change in discriminatory value attitudes is particularly crucial.

Policy Implications

The G20 states are in at least verbal agreement that gender justice is fundamental to sustainable and socially just economic growth. The increase in women’s labour market participation should be seen as just one step in the right direction. To help create vital jobs in India, Germany should advocate for holistic political measures in the context of its G20 presidency, and the EU and the G20 should support India in its attempts to open markets and attract direct investment.

The G20 and Global Social Problems

It may come as a bit of a surprise that the informal club of the economically and politically most powerful countries on Earth is now also dedicating itself to “soft” topics. Since its significance increased in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008/09, the G20 has dealt primarily with “hard” economic and financial issues. In recent years, however, the group has taken on topics such as the globally increasing concentration of wealth, global unemployment (especially among young people), poor working conditions, and, last but not least, inequalities between men and women in the workplace. This trend emerged from a context in which the original approaches to overcoming the financial crisis tied in closely with topics of financial market regulation; the dampening of global economic imbalances; the avoidance of fiscal and monetary competition; energy and climate policy; the fight against corruption and terrorism; and the promotion of development, social inclusion, and a more equitable distribution of wealth. In that context, the topic of eliminating, or abating, global gender discrimination was close at hand. The recognition that gender inequality is not only a question of social justice but also one of immense economic importance contributed to this trend (OECD, ILO, World Bank, and IMF 2014).

One can, of course, question whether this broadening of the G20 agenda really led to an increase in the impact of its action plans or the dedication of its member countries to the group’s jointly declared objectives. The 2012 G20 summit in Mexico, for example, resulted in more than 50 recommended individual actions in its final declaration, for which 27 international organisations were called upon for assistance (Knaack and Katada 2013). The Turkish proposal for the 2015 summit in Antalya contained 35 broad areas of action, while the German proposal for the upcoming summit in Hamburg contains no less than 16. When looked at in a positive light, the multiplication of the fields of action could be seen as a movement toward a holistic perspective of global development. However, when seen negatively, it could be regarded as a reaction to the ineffectiveness of earlier, more narrowly based recommendations in the political core areas of economic and financial policy. In this respect, things are not looking very good, especially for the less developed members of the G20 (Kirchner 2016), nor does this bode well for the promotion of gender equality, though fatalism would be out of place.

In the following, we seek to highlight the context in which gender equality became a topic at the G20 level. To illustrate this process, we examine the current situation in India with regard to the participation of women in the workforce. Based on this, we develop possible solutions to be derived within the G20 and discuss the role of Germany and other industrialised countries.

The G20, the W20, and the Demand for Gender Equality

The international debate on the empowerment of women and gender equality goes back several decades and celebrated its first success at the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), adopted in 1979 – and ratified in 1993 by India as well. CEDAW was followed by the Beijing Declaration in 1995, which includes a number of gender equality principles. At the level of the European Union (2002) and the African Union (2005), gender equality has likewise been officialised through contracts. In 2015/16, the international community also agreed on the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) (Agenda 2030), with Goal 5 explicitly requesting gender equality and Goal 8 demanding full and productive employment for women and men alike as well as equal pay for work of equal value by the year 2030.

At the G20 level, gender inequality was first addressed at the 2012 Los Cabos summit, where the low social and economic participation of women was identified as a major obstacle to economic development. At the Saint Petersburg summit a year later, the demand was made for more financial education for women, among other things as a means to develop women’s entrepreneurial potential. The Brisbane Action Plan (G20 2014), for its part, stated as its first concrete goal that the gender gap in labour market participation be reduced by 25 per cent by 2025 – albeit in a somewhat diluted form due to the phrase “taking into account national circumstances.” In the following year at the summit in Antalya, the obligation to monitor the participation rate of women then became more binding. The Antalya summit was also where the initial steps were made for Women 20 (W20), a G20 dialogue group dedicated to the promotion of women in the member countries and constituted solely of female delegates from the G20 countries.

The W20 meets regularly before each G20 summit and met most recently in Berlin from 24 to 26 April 2017. At the 2016 G20 summit held in Hangzhou, the G20 action plan did not add anything new as regards gender, which might have been due to the fact that China wanted to keep the agenda rather limited and that gender equality was not one of the main goals (see Biba and Holbig 2017). Moreover, although the summit had pledged to play a pioneering role in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and to orient its own action toward the sustainable development goals (SDGs), Goal 5 (gender equality) was not given any particular priority (see G20 2016). Nonetheless, the W20 evolved and became stronger with this summit too. For the summit in Hamburg this year, under the presidency of Germany, the German federal government formulated a priority plan that focused mainly on the core themes of the G20. These are: economic development; strengthening the global financial architecture; international trade and employment; and, somewhat secondarily, the elimination of discrimination against women in employment, pay, and digital inclusion, as well as access to loans for business start-ups.

The W20 is, in comparison, much more concrete in its support for women. For example, it calls for gender-based tax revenue assessments, analyses, and budget planning in all areas, as well as the preparation of national action plans regarding the Brisbane gender gap goal, including the monitoring of progress with the help of the OECD and the ILO. It also pursues the targeted promotion of female entrepreneurs and women’s cooperatives; the special digital support of girls and women; and the complete closing of gender gaps in training, education, and pay. Finally, the W20 calls for the elimination of legal barriers to women’s economic ownership and aspires to break societal norms that discriminate against women and to fight against violence against women – all measures that have been sorely missed in the G20 action plans (Women 20 Germany 2017).

It is striking that women’s increased participation in the labour market, in the allocation of loans, and in terms of digital inclusion has thus far been seen in all action plans primarily in light of the contribution to economic progress and increased productivity, in other words, as purely functional. This means that the reduction of social inequalities, and the associated dangers of such inequalities to social stability, has played only a secondary role and has almost never been seen as a human value to be promoted in and of itself. Yet all the while, ensuring that half of the world’s population can participate equally in all areas of life should be, or is, a matter of protecting human rights and social justice. A hint of hope is that this year’s G20 is putting an increased emphasis on the quality of labour and employment relations, pay gaps, and old-age poverty of women. This can be seen from the final declaration of the meeting of the G20’s labour ministers on 18 and 19 May in Bad Neuenahr (G20 2017), which extended well beyond matters concerning economic growth.

Mixed Success among the G20 Members

The evaluation of progress made in the consideration of women’s rights in the G20 leaves little room for euphoria and optimism. The fact that it was possible to even agree on a definite goal, in Brisbane, for closing the gender gap in labour by 25 per cent can be attributed to the demographic development of some the member countries. The EU28 countries as well as China, Japan, Korea, and Russia are anticipating, some to significant degrees, a decline in their overall labour force participation rates (with a corresponding impact on growth and economic momentum) if the participation rate of women does not increase (OECD, ILO, World Bank, and IMF 2014). Germany, for example, anticipates a decline in its labour force participation rate of up to 10 per cent by 2025 should nothing change in the current situation. At the same time, the goal of increasing the G20’s gross domestic product over the next five years by 2 per cent beyond the expected growth would hardly be possible without a rise in the women’s employment rate.

The G20 member countries by no means finish first when it comes to achieving gender equality. According to the aggregated indicator of the Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum 2016), they tend to be in the lower or middle ranks among the 144 countries for which complete data sets are available. Germany ranks 13th, which is relatively good, but is surpassed by the Scandinavian countries and even a few developing countries. Saudi Arabia ranks number 141, while Turkey, South Korea, and Japan are also far behind. China, Indonesia, India, Brazil, and Russia are likewise on the lower end of the spectrum. When only the indicator “economic participation and opportunities” is taken into account, the emerging markets fall back even more in the ranking, in particular India, Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil. That said, many other countries fail to get good marks in this respect as well, including Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Korea, Japan, Italy, and South Africa. This is far from being an impressive result.

In the following, we present the situation of women, alongside associated government measures, in India. The country seemed to offer a useful example given the enormous population size and the global media attention garnered by gender issues, especially violence against women. In addition, unlike the case for the highly populated China, for example, reliable data on gender discrimination is available for India.

Participation of Women in India

India still has a young and growing population and will replace China as the most populous country in the world in the foreseeable future. Over the past 10 years, India’s population has grown by about 180 million to about 1.26 billion people. This means that India’s labour pool will be growing for a longer time, which constitutes a competitive advantage. That said, a growing reserve labour pool can also become a burden when an economy is unable to provide sufficient jobs.

Since 2000, India’s economy has repeatedly seen growth of 8 per cent or more. At 7.5 per cent, India is currently the fastest-growing G20 economy. However, despite high economic growth, the number of jobs has grown only slightly – a phenomenon which economists refer to as “jobless growth.” In India, this is due mainly to the services sector, which is responsible for most of the growth yet which has created few jobs. In addition, India has to contend with weak industrial growth, a declining agricultural sector, the global downturn as a result of the financial and economic crisis in 2008, and the increasing mechanisation of formerly labour-intensive industries.

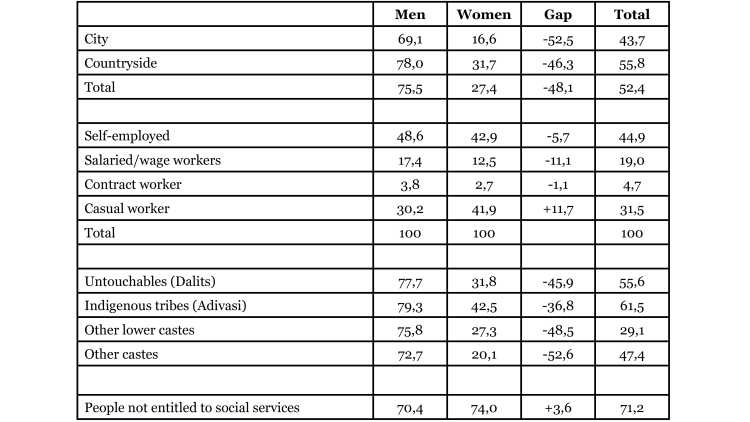

According to the Indian government’s current employment report (Government of India 2016a), only 27.4 per cent of women are currently employed, compared with 75.5 per cent of men (aged 15 years). This corresponds to a gender gap of approximately 48.1 percentage points. Indeed, this places India second to last, after Saudi Arabia, of all G20 countries with regard to the participation of women. In addition, compared to Saudi Arabia, the women’s employment rate in India has even declined over the last decade. According to calculations done by Lahoti and Swaminathan (2016), the women’s employment rate (for 25- to 59-year-olds) decreased by 25 percentage points between 1983 and 2012.

One likely reason for the decline in the women’s employment rate is that women are increasingly pursuing lengthier training and education programmes and pathways, resulting in their postponed entry into the labour market. In addition, with an increase in India’s median household income, women are less compelled to generate an additional income – although this often sets them back into the role of the housewife. Another main reason is that, compared to China and Bangladesh, India’s growth is based primarily on domestic demand (ADB 2017) and relies only to an insignificant degree on the export-oriented, processing industry. In rural areas, employment opportunities for women have dwindled and have not been offset by new jobs outside agriculture. In addition, the need for women with better-educated backgrounds is rather low in the service sector.

India’s working women work primarily under precarious terms and conditions, a situation that has been exacerbated by the increase in informal employment. Most newly created jobs have been generated in the organised sector, yet have nonetheless been informal in nature. Formal employment, for its part, has even declined. According to official data (see Table 2), the majority of women in employment are either self-employed (42.9 per cent) or are employed as casual workers (41.9 per cent). The proportion of employees and regular wage earners is just 12.5 per cent. This means that approximately 74 per cent of the female workforce is not entitled to social benefits (Government of India 2016a). As in the industrialised countries, women in India are, on average, paid less for equal work. It is estimated that the average hourly wage gap is higher than 30 per cent (ILO 2016).

Overall, the rate of women’s employment in India is higher in rural regions than in cities. In addition, it varies significantly across regions – for example, between 10 (Bihar) and 68 per cent (Himachal Pradesh) in 2009/10. Differences in the participation of women are also found between social groups. Women belonging to the Dalit caste (untouchables) or an Adivasi tribe are more employed than women from other disadvantaged castes or higher castes (see Table 2). The lowest labour participation rate is found among women of the Muslim minority.

The deep-rooted gender inequality in the labour market – and beyond – results from the fact that India is still a male-dominated society. Men control the political, economic, religious, social, and cultural spheres. Society’s dominant patriarchal norms and values not only hamper the entry of women into the labour market but also the success of working women. These norms and values are often passed on and even legitimised within the family, caste, community, and religion. This is reflected in discriminatory practices such as gender-specific abortions, violence of all kinds against girls and women, and gender disparities in education and health (see Drèze and Sen 2014). For example, in spite of all efforts at state intervention, India still has an alarmingly low ratio of females to males, which has worsened in the past two decades. According to recent surveys, there are only 919 female children per 1,000 male children (Government of India 2016b).

Measures Taken by the Indian Government

Due to its population trend, India faces the challenge of having to provide sufficient and good jobs for its young and growing population. Given that the current economic growth has created fewer jobs than hoped for, the current government coalition under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been, since 2014, pursuing a clear strategy for achieving employment-intensive economic growth.

One of the most important measures under the motto “Make in India” is to expand India into a global production location. Plans are to increase the share of industrial production in the gross domestic product from 15 to 25 per cent by 2022, thereby creating 100 million new jobs. A total of 25 industry sectors have been selected as investment targets and partly opened to foreign direct investment (Neff 2015). One of them is the textile and clothing industry, which mainly employs women.

From a purely mathematical point of view, however, a total of about 64 million jobs for women would have to be created in order to close the gap in the labour force participation. In view of the current decline in the rate of women’s participation in labour, this objective does not appear to be realistic. At the same time, the question arises whether the world economy still has room for a “second China” that is focused on labour-intensive products. For even if labour-intensive production sectors were to withdraw from China, the increase in the number of jobs for India might well be small given the growing automation and digitisation of labour that is affecting all sectors. Moreover, jobs in the textile industry are generally poorly paid and thus hardly contribute to the economic empowerment of women.

In addition to the goal of creating jobs in the manufacturing sector, India’s government under Modi is also supporting, through its “Start Up India” initiative, entrepreneurs through loans, tax cuts, and a reduction of bureaucracy. These efforts are explicitly targeted to women alongside the other disadvantaged social groups. Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel demanded in April 2017 at the W20 meeting in Berlin that women entrepreneurs be promoted specifically through loans. However, in India many women work as micro and small entrepreneurs, and can barely keep themselves above water. Moreover, contrary to expectations, the majority of these entrepreneurs are not creating additional jobs but are only active for a lack of alternatives.

What Can Germany’s G20 Presidency Do?

On 1 December 2016, Germany took over the G20 presidency. Among its priorities for the summit in Hamburg on 7 and 8 July 2017 is the goal of increasing the benefits of globalisation and distributing them more broadly (G20 2017). The identified priorities are to strengthen the economic power of the member countries and sustainable development. The topics of digital inclusion – a favourite of the federal chancellor – and the empowerment of women are subsumed under sustainability.

Since the W20 is likewise supportive of grouping gender equality under sustainability, the German federal government has the opportunity to have significant influence on the agenda and action plan at this year’s summit. However, whether successful negotiations will then translate into actual improvements for women in practice is another question. It has often been pointed out that improvements in the legal framework or the establishment of institutions for the advancement of women do not always manifest in actual improvements. This applies even more to international agendas and communiqués, which include neither binding international obligations nor sanctions – all of which is well-known. It would therefore be advisable to plan all the measures carefully and by drawing on professional expertise in order to be able to implement them in a targeted manner (Narlikar 2017). In addition, it would be useful to complement the often flowery declarations of intent through verifiable objectives and timetables, which would open up the possibility of collective criticism and peer pressure from other member states. A suitable instrument would be, for example, performance monitoring under the aegis of the W20. The members of such a committee should, in accordance with the W20 recommendations, be offered insight into the G20 negotiations and Sherpa meetings.

Essentially, the problem of all policy measures for advancing equality is that they are planned individually and do not have an overview of the bigger picture of gender relations. Within the framework of the decisions of the G20 countries, it has become clear that although it is possible to agree on the financial and, probably soon, digital inclusion of women, the task of promoting the social and political participation of women will remain with the individual member countries. Compared to other global problems such as climate change, gender equality is viewed primarily as a problem to be solved at the national level. For this reason, a stronger focus on SDG Goal 5 at the G20 level would not suffice to ensure significant progress.

Against this background, it is all the more important to make sure that the more holistic policy measures identified by the G20 ministers in 2014 and most recently in 2017 (see G20 2014; G20 2017) are implemented in the individual countries. These measures include, in addition to lifelong education and training, the expansion of childcare and the provision of care for the elderly; paid parental leave; family-friendly jobs; the abolition of legal restrictions with negative impacts for women; the fight against discrimination in the workplace, including that related to remuneration and promotions; the expansion of the social safety net (especially for workers in the informal sector); and an increase in the proportion of women in management positions. Here as well, intensive monitoring could have a positive effect.

However, the tenacious anti-feminist norms and values that still prevail in India are hardly something that can be quickly dissolved or transformed. Nonetheless, it is safe to assume that economic development and better education for women and, to a certain extent, increased formal employment opportunities for women alongside corresponding incomes would contribute to a change in values. A prominent example of this is India’s neighbouring country, Bangladesh, where the sex ratio at birth is fully in line with the biological standard. The factors contributing to this success – a combination of a labour-intensive industrialisation strategy (with a focus on clothing), a greater supply of jobs for women, and the expansion of state-funded education for women – have increased the economic participation of women within two decades and have, together, allowed for the normalisation of gender relations. That said, the level of women’s earnings in Bangladesh is still far from providing women with real financial empowerment and women are still subject to discrimination.

The Western industrialised countries could, from the outside, advance the cause of women in India by supporting women’s development cooperation with India (which has been stagnating since 2008) – namely, by supporting new and existing industries (as suggested by the G20 labour ministers) and by providing women with professional training opportunities for medium-level jobs. The latter measure is important since the labour-intensive industrialisation policy pursued by India calls for a massive pool of labour, especially female, with a mid-range rather than university-level education.

The Federal Republic of Germany is well positioned to provide career and job training assistance of this type, and the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ, Agency for International Cooperation) – one of Germany’s main development aid agencies – is already active in the “Skill India” initiative in India. Furthermore, to realise this strategy at the EU and G20 levels, open markets, alongside appropriate direct investments, should also be encouraged, as should the support of Indian women’s associations. Finally, Germany and the EU must not underestimate the value of setting a good example in closing the gender gap in pursuing these goals. That said, it is worth remembering that the main responsibility for improving these societal conditions lies with India itself and that only a limited amount of progress can be achieved from the outside.

Footnotes

References

ADB (Asian Development Bank) (2017), Asian Development Outlook 2017. Transcending the Middle-Income Challenge, Manila: ADB.

Biba, Sebastian, and Heike Holbig (2017), China in the G20: A Narrow Corridor for Sino–European Cooperation, GIGA Focus Asia, 2, Hamburg: GIGA, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/china-in-the-G20 (27 May 2017).

Drèze, Jean, and Amartya Sen (2014), Indien: Ein Land und seine Widersprüche, München: C.H. Beck.

G20 (2017), Towards an Inclusive Future. Shaping the World of Work, G20 Labour and Employment Ministers Meeting 2017, Ministerial Declaration, www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Pressemitteilungen/2017/g20-ministerial-declaration.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (22 May 2017).

G20 (2016), Action Plan on the Agenda for Sustainable Development, www.b20germany.org/fileadmin/user_upload/G20_Action_Plan_on_the_2030_Agenda_ for_Sustainable_Development.pdf (25 May 2017).

G20 (2014), Brisbane Action Plan, Melbourne, www.g20australia.org/official_resources/brisbane_action_plan.html (20 April 2017).

Government of India (2016a), Employment and Unemployment Survey, Vol. 1, Vol. 2, and Vol. 4, Chandigarh: Ministry of Labour and Employment Labour Bureau.

Government of India (2016b), National Family Health Survey – 4, 2015/16, India Fact Sheet, Mumbai: International Institute for Population Studies.

ILO (International Labour Organisation) (2016), Global Wage Report 2016–17, Wage Inequality in the Workplace, Geneva: International Labour Organisation.

Kirchner, Stephen (2016), The G20 and Global Governance, in: Cato Journal, 36, 3, 485–506.

Knaack, Peter, and Saori N. Katada (2013), Fault Lines and Issue Linkages at the G20: New Challenges for Global Economic Governance, in: Global Policy, 4, 3, 236–246.

Lahoti, Rahul, and Hema Swaminathan (2016), Economic Development and Women’s Labor Force Participation in India, in: Feminist Economics, 22, 2, 168–195.

Neff, Daniel (2015), Beiträge im Wirtschaftslexikon: Amtsschimmel, Demografie, Infrastruktur, Make in India, Ungleichheit, Internationale Politik, Sonderheft Indien, 3.

Narlikar, Amrita (2017), Can the G20 Save Globalisation?, GIGA Focus Global, 1, Hamburg: GIGA, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/can-the-g20-save-globalisation (18 May 2017).

OECD, ILO, World Bank, and IMF (2014), Achieving Stronger Growth by Promoting a More-Gender-Balanced Economy, www.oecd.org/g20/topics/employment-and-social-policy/ILO-IMF-OECD-WBG-Achieving-stronger-growth-bypromoting-a-more-gender-balanced-economy-G20.pdf (18 May 2017).

World Economic Forum (2016), The Global Gender Gap Report 2016, Geneva.

Women 20 Germany (2017), Implementation Plan, Putting Gender at the Core of the G20, www.w20-germany.org/fileadmin/user_upload/W20_IP_2017.pdf (24 May 2017).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Asia

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Asia

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Neff, Daniel, and Joachim Betz (2017), Gender Justice as an International Objective: India in the G20, GIGA Focus Asia, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-52138-9

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.