- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- "Micronexit" Overshadows Golden Anniversary of the Pacific Islands Forum

GIGA Focus Asia

"Micronexit" Overshadows Golden Anniversary of the Pacific Islands Forum

Number 2 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-359X

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) faces the biggest crisis since its founding 50 years ago. All five Micronesian states, nearly one-third of PIF members, are to leave the organisation in 2022 because their secretary-general candidate was not elected in early 2021. Reforms may help to avert “Micronexit,” but challenges still abound for the Pacific’s premier regional body.

Since 1971, the PIF has been at the heart of Pacific regionalism. Regional integration remains shallow, but the Forum has a number of achievements to show for itself.

China’s growing regional engagement has provided Pacific Island Countries with increased agency and international attention. Australia and New Zealand, the established regional powers, have devoted more resources to the region while the United States is also showing interest again.

The PIF’s 50th anniversary in August 2021 could be used to make the most of that growing interest by highlighting climate change- and COVID-19-related regional challenges. Instead, the anniversary now threatens to be overshadowed by the spectre of Micronexit and a crisis of the University of the South Pacific, the region’s showcase cooperation project.

Micronesia’s grievances about South Pacific dominance need to be addressed. Possible institutional reforms include formalised rotation of the secretary-general job among the Pacific subregions.

If PIF member states fail to rise to the occasion, the Forum’s credibility in the eyes of external partners will suffer and the Pacific’s voice and weight on global issues such as climate change and sustainable ocean governance will weaken.

Policy Implications

A PIF that speaks for the whole region is a valuable partner for the European Union. The EU has thus signalled its interest in a “united, inclusive and balanced” PIF. Other PIF dialogue and development partners should follow suit. In its planned Indo-Pacific strategy, the EU should give adequate attention to the PIF and the region it stands for. Intensified political and strategic dialogue between the EU and the Pacific region would be desirable.

Crisis and Opportunity

Like other regional organisations, the PIF has seen its share of crises. The most severe one, up until recently, occurred in 2009. At the time, Fiji’s membership was suspended after Prime Minister (PM) Josaia Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama failed to restore democracy following the 2006 military coup there. The suspension marked a major departure from the non-intervention principle that had underpinned Pacific regionalism ever since 1971 (Fry 2019). Only after free elections were held in 2014 was Fiji allowed to return to the fold. And only in 2019, a full decade after the suspension of its membership, did Fiji start to participate again at the PM level in PIF summits. Upon his return to the Forum, Bainimarama offered to host the 2021 summit. He also wasted no time in late 2020 in inviting United States president-elect Joe Biden to attend the summit.

After four years of the Donald Trump administration walking away from the Paris Agreement and frustrating efforts to deal with the challenge of climate change, high-level US participation in the PIF summit would be more than welcome. It would provide Pacific Island Countries (PICs) with an opportunity to highlight the importance of the issue. It would also enable them to put more pressure on Australia to stop giving its coal industry precedence over combatting climate change.

Any high-level US participation in the August 2021 PIF summit is, however, unlikely unless the PIF can overcome its most recent institutional crisis of February 2021. In view of the PIF’s golden anniversary, essential background information on the regional organisation is first provided in the following – also taking note of its achievements and the recent renewal of geopolitical competition in the region. Then the PIF’s current crisis is elaborated on, with possible reforms that may help overcome it being highlighted. The policy implications for the European Union and beyond are offered in closing.

Pacific Regionalism: A Backgrounder

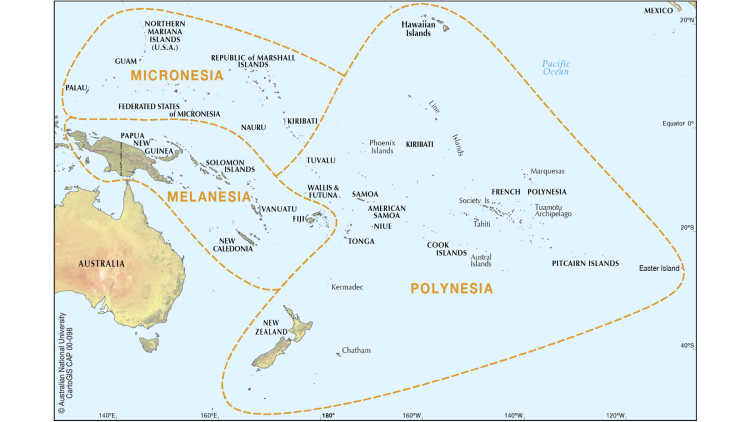

The PIF will celebrate this year the 50th anniversary of its founding in August 1971. The establishment of what was then called the “South Pacific Forum” – the founding members were all located south of the equator – took place against the backdrop of late decolonisation in the region. Newly independent nations in both the South and the North Pacific, from Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia (see Figure 1 below), joined the regional organisation in the following decades, also leading to the name change to “Pacific Islands Forum” in 1999. More recently, the PIF changed its policy of only accepting sovereign nations as full members. French overseas territories French Polynesia and New Caledonia thus joined in 2016, bringing the PIF’s core membership to 18-strong and making it even more inclusive.

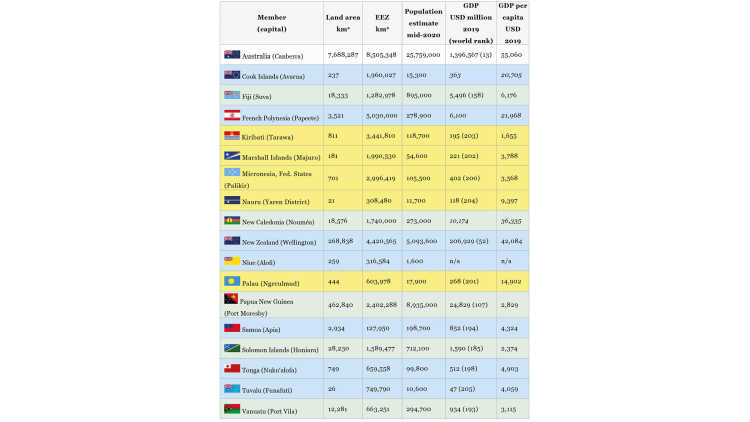

PIF member states are a diverse group, differing in development status and relations with regional powers. Apart from the region’s established powers Australia and New Zealand, and also Papua New Guinea, all PIF members are microstates. They have small economies, but nevertheless call large maritime Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) their own. The population of the PICs ranges from 1,600 people in the case of Niue to close to nine million in that of PNG (see Table 1 below). Fisheries, and in some cases tourism, loom large in the economies of many PICs. Only Melanesia is endowed with substantial non-marine natural resources. Collectively, the PICs constitute on a per capita basis the most aid-dependent region worldwide. The main development partners are Australia and NZ, with the People’s Republic of China, the EU, Japan, Taiwan, and the US also figuring prominently as providers of aid. The EU as well as 15 individual countries, including France, the United Kingdom, and, since 2016, also Germany, are PIF dialogue partners.

As the most inclusive and best-resourced regional organisation, the PIF is at the heart of Pacific regionalism. But it is not the only regional body. A host of regional agencies are linked to the PIF under the umbrella of the Council of Regional Organisations in the Pacific (CROP). In addition, subregional groupings not formally connected to the PIF exist in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Further cooperation and dialogue processes in the Pacific include those connecting the PRC and Taiwan to their respective diplomatic partners in the region, making the Pacific one of the “most workshopped […] regions in the world” (Beck 2020: 14). The Pacific’s complex “patchwork” regional architecture also includes the Pacific Community and the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF). The latter was set up by Fiji in 2013 while suspended from the PIF. The 12-member PIDF exemplifies Fiji’s activist foreign policy under Bainimarama. While Fiji has managed to punch above its weight in international affairs in recent years (see Wyth and Stünkel 2021), the country’s regional-leadership ambitions have rankled other Pacific states – including its old rival Samoa. Fiji also tried to dislodge Australia and NZ from the PIF, but ultimately failed.

As with most regional organisations, the cooperation of PIF member states does not involve the pooling of sovereignty. Overall, the level of regional integration has remained low. A successful exception is the Nauru Agreement, which regulates fishing in the vast EEZs of the Pacific. The University of the South Pacific (USP) is another showcase regional-cooperation project. Others, namely an airline and a shipping line, no longer operate as regional entities. Trade and capital flows among PICs are limited. Their main economic linkages are with Australia, NZ, and for some time now also with the PRC. The Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) Plus, a trade pact promoted by Australia and NZ, does not include the regional heavyweights PNG and Fiji as they were not convinced about the benefits of membership. Other countries only signed up to the pact in exchange for Australian and NZ concessions on labour migration.

On other issues also, Australia – the South Pacific’s “resident superpower” in terms of gross domestic product, defence spending, population, and development assistance (Wallis and Wesley 2016: 26) –, NZ as the other established regional power, and the PICs do not always sing from the same hymn sheet. Australia and NZ have had a huge impact on Pacific regionalism, but there has also been frustration on the part of PICs about their dominance in regional affairs – especially in the 1990s and first decade of the new millennium when the two Australasian allies pushed a neoliberal agenda of economic adjustment and a geopolitically focused security policy on the region (Fry 2019). The strategic priorities and foreign policy outlooks of PIF member states clearly differ, with Australia and NZ sometimes aiding, sometimes hindering a unified regional stance. Most prominently, the PICs differ from Australia in terms of climate policy. Perspectives on the PRC’s role in the region also diverge (Köllner 2020).

Diplomatic Achievements and Climate Policy Advocacy

Despite such challenges, the PIF matters in terms of both regional and global affairs. In its 50-year history, PIF members (with or without Australia and NZ) have manifested important diplomatic and other achievements, for example with respect to:

establishing terms, often as part of the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (ACP), with the EU on a host of trade and partnership agreements since 1975;

maritime governance, helping to develop the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), banning drift-net fishing, hindering Japan from dumping nuclear waste in the Pacific, and establishing fisheries agreements with major powers;

nuclear tests in the South Pacific, with the 1985 Treaty of Rarotanga (South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty) establishing a regional ban on nuclear weapons and their testing;

promoting decolonisation, reinstating New Caledonia (1986) and French Polynesia (2013) to the UN’s decolonisation list;

security cooperation, most notably in the context of the Australia-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (2003–2017); and,

establishing joint positions on climate change, most prominently in the run-up to the Paris Agreement (due to Australia and NZ’s diverging positions, the main coordinating body here was the Pacific Small Islands Developing States, PSIDS, grouping at the UN, with the PIF Secretariat providing support).

Importantly, Pacific regionalism is not only about intergovernmental cooperation but has also involved numerous civil-society and other bottom-up activities at the regional level, for example in the anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s and 1980s.

Given their vast maritime zones and the vulnerability of low-lying atolls in the Pacific, PICs have been particularly outspoken when it comes to ocean governance, climate change, and the related problem of rising sea levels. These issues have provided them with new platforms, ones used to emerge as a kind of global leader – both morally and more besides. They have used the PSIDS grouping at the UN to participate actively in international negotiations, to vote as a bloc, and to place candidates in selected international positions (Beck 2020). Especially with their prominent advocacy on climate change policies, PICs can appear to outsiders like a unified bloc – which, however, they are not, as the recent crisis underlines. But it is true that in terms of rallying effects, emotional commitment, and collective action the issue of climate change has become for PICs what nuclear testing was a few decades earlier (Fry 2019).

Guided by the “Blue Pacific” narrative, which seeks to replace the image of small, isolated, and fragile states with the notion instead of “large ocean states,” PIF member states and their citizens have also been moving towards a regional, “pan-Oceanic” identity. The narrative emphasises that the states and societies of the “new Oceania” share stewardship of the Pacific Ocean (Fry 2019). PICs have become more active and creative in asserting their agency, with the Blue Pacific concept emblematic of this new-found assertiveness (Morgan 2020).

Geopolitical Competition in the Pacific

The PRC’s increased regional engagement, alongside recent initiatives by Australia and NZ to balance this engagement by providing more aid and devoting more attention and diplomatic resources to the region, have increased the options open to PICs (Fry 2019; Köllner 2020). The US reduced its presence in the region after the Cold War, closing aid and diplomatic offices and withdrawing Peace Corps volunteers. But given the perceived regional challenge from the PRC it has recently shown more interest in the PICs again. In May 2019, Trump met at the White House with his counterparts from the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and from Palau, pledging increased support for them. Negotiations to renew these countries’ free association with the US commenced in August 2019 when Mike Pompeo paid an official visit to the FSM, a first for a US secretary of state. The momentum continued in 2020 too. The US secretary of defense at the time, Mark Esper, visited Palau, and in July the “Boosting Long-term U.S. Engagement in the Pacific” (BLUE) Pacific Act was introduced in Congress. If passed it would increase annual US assistance to the Pacific region by USD 1 billion over a five-year period, effectively tripling current spending levels.

Foreign policy and security establishments in both Washington and Canberra view the Pacific islands (again) through the prism of global geopolitics. They understand the PICs today as a subregion of the Indo-Pacific – an emerging geostrategic space and arena of PRC–US geostrategic competition (Morgan 2020). During the Cold War, Australia and NZ’s “strategic denial” approach aimed at preventing potentially hostile powers from establishing a foothold in the South Pacific, with the two allies serving as “gatekeepers” on behalf of the West. In the 1970s and 1980s it targeted primarily the Soviet Union. The approach has been revived – not officially, but in practice – in recent times to respond to the PRC’s increased regional presence. It is, however, unclear whether “strategic denial” was successful in its own right during the Cold War. And it is even more questionable what it can achieve today. At best, it might prevent the PRC from setting up a military base in the region – should such plans even exist. It will, however, not dislodge the PRC from the region given the scale of its engagement and the interest of most PICs in productive relations with the East Asian country (Fry 2019; Morgan 2020).

The PICs themselves have no interest in becoming pawns in some geostrategic game or, for that matter, in the militarisation of their home region. However, they do benefit from the increased attention and resources which the great powers and their allies and partners offer. As long as they are not forced to choose sides, the geostrategic dynamics at play in the wider region – including geo-economic initiatives like Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative – afford them greater agency.

The PIF Facing a Twin Crisis …

Reaching the PIF’s 50th anniversary would normally be reason to celebrate. The occasion could also be used to highlight how the Pacific has been affected by two key challenges: the longer-term existential one of climate change and the short- to medium-term health and economic issues posed by COVID-19. French Polynesia and PNG aside, PICs have been able to avoid large-scale infection rates. However, they have needed testing kits, protective equipment, and vaccines. Big donors such as Australia, New Zealand, and the PRC responded to demand by adjusting their development-assistance flows and providing humanitarian supplies. The economic effects of the pandemic loom much larger. Given the substantial role that tourism plays in their economies, some PICs were especially hard hit by international-travel restrictions. Economic activity in the region is estimated to have contracted by more than 5 per cent in 2020, with per capita income falling by around 9 per cent – “setting average living standards back by almost a decade” (Dayant 2021).

While individual PICs are struggling under the impact of the pandemic, the PIF recently encountered the biggest crisis since its founding. It erupted at a virtual leaders’ meeting in early February 2021, with the election of a new secretary general being the sole item on the agenda. The secretary general is the PIF’s most senior civil servant, managing a budget of close to EUR 70 million and, among other tasks, chairing the CROP and the specialist subcommittee on regionalism as well as serving as Pacific Ocean Commissioner. The outgoing office holder, Dame Meg Taylor, a former high-ranking World Bank official, has been credited with providing the PIF with new momentum and helping to make audible a distinct Pacific voice on both regional and global matters. Out of the five secretary-general candidates emerging in 2020, only two stood a real chance of succeeding her. The Micronesians had agreed on Ambassador Gerald Zackios, a representative of the RMI to the UN and a former foreign minister of his country. The other strong candidate, Henry Puna, had resigned as Cook Islands PM to run for the PIF secretary-general post (Sen 2020).

The Micronesian states believed that it was their turn. Since 1998, the post had been held by someone from either Polynesia or Melanesia. Even though the five Micronesian states are small even by Pacific standards, this does not make their candidates less eligible – provided they are qualified for the top PIF job. It is claimed that in 1978 a “gentlemen’s agreement” on taking turns among the subregions was born (Fry 2021). The agreement helped to address Melanesian grievances at the time about Polynesian dominance of the Forum. Now it was Micronesian grievances about South Pacific dominance which came to the fore, especially as two earlier Micronesian candidates had not been elected in 2003 or 2014 respectively. Micronesian leaders warned of consequences if their candidate was overlooked. These warnings were either ignored, not taken seriously, or seen as extreme in the first place. In any case, in the leaders’ meeting of 3 February 2021 Puna received one vote more in the final tally than Zackios. There was speculation whether a physical meeting would have led to a more consensual outcome, but the result ultimately stood. The presidents of the FSM, Palau, and the RMI subsequently made good on their earlier promise: they announced their impending withdrawal from the PIF, to become effective in a year’s time thence. Kiribati and Nauru were assumed to be set to follow suit, though official confirmation was still lacking as of late March.

While “Micronexit” was in the making, a second crisis engulfed the PIF too. With attention turned towards the contentious leaders’ summit, Fiji deported the vice-chancellor (VC) of the USP – whose main campus is located in Suva. Fiji accused VC Pal Ahluawalia of violating Fiji’s Immigration Act. More to the point, the USP vice-chancellor had been a thorn in the side of the ruling FijiFirst party, making public the financial mismanagement of his predecessor who was close to the government in Suva (Howes and Sen 2021). The deportation turned USP’s governance problems, which had been brewing for some time, into a genuine regional crisis that also demands institutional reform. It showed that domestic issues matter more to the Fijian government than the reputation of regional institutions. More generally, the USP crisis underlines how brittle institutionalised Pacific regionalism is and how easily national impulses can trump regional achievements and aspirations (Tukuitonga 2021). The irony is that, as the incoming chair of the PIF, Fiji will have to play a vital role in sorting out the twin crisis that now overshadows the Forum’s golden anniversary and the summit which it will host later this year.

As Ratuva and Teaiwa (2021) note, the twin crisis facing the PIF raises questions about the resilience and sustainability of formal institutionalism in the region. If the PIF is not able to successfully overcome these parallel challenges, substantial damage will be done to the Pacific’s premier regional organisation. Micronexit would reduce the PIF’s weight at the UN and in international negotiations. The PIF would no longer be able to speak for the entire Pacific, reducing its legitimacy as the region’s preeminent body. The organisation’s credibility in the eyes of external observers would decline, and so might the willingness of overseas partners to support regional activities.

Trying to further their own interests, the great powers might be tempted to try to play remaining members off against one another. Certainly, the leverage of PICs vis-à-vis external partners would decline; bilateral relations might increase in importance meanwhile (Pryke 2021; Ratuva and Teaiwa 2021). The US’s interest in the PIF would diminish again, as the subregion closest to it would no longer be a part of that organisation. There might also be pressure on the two Micronesian states with diplomatic links to Beijing (Kiribati and the FSM) and the only remaining South Pacific state with diplomatic links to Taipei (Tuvalu) to switch sides.

… and What Can Be Done About It?

How can the PIF ward off such a scenario? How can Micronesian member states be persuaded to rescind their withdrawal? For one, their grievances in face of South Pacific dominance would need to be properly addressed. A PIF statement apologising to the Micronesians for how things played out might be a good starting point. Concrete suggestions on how to move ahead include making a firm commitment that the next secretary general will come from Micronesia. Beyond that, informal norms and institutions – open to different interpretations such as the above-mentioned gentlemen’s agreement on rotation in leadership positions – would need to be replaced, or at least complemented by transparent formal procedures enabling greater reliability of expectations. A formalised rotation of fixed-term leadership positions among the Pacific’s subregions of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia – similar to what exists in the case of the ACP – or, potentially, the introduction of formal dispute-settlement mechanisms would also need to be implemented (Pryke 2021; Ratuva and Teaiwa 2021).

The role of existing subregional groupings – the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), the Micronesian Presidents’ Summit, and the Polynesian Leaders Group – could well increase as a consequence of the crisis (Tukuitonga 2021). They could be given caucus status within the PIF, and be used to vet and decide on qualified secretary-general candidates. In addition to the existing MSG Secretariat there could be similar offices for the two other subregional groupings. Even prior to making such changes, the PIF might want to give sufficient room to Micronesian issues and concerns – with perhaps a special mandate in this regard for the current deputy secretary general, who has lived in Micronesia for some time. In any case, Micronexit is not a foregone conclusion. Given the necessary political will exists on the part of PIF member states, it can still be avoided.

The USP crisis is perhaps an even thornier issue as it involves domestic politics and lacking respect for the rule of law. As long as Fiji treats the university as a national institution and issue, it cannot properly function as a regional organisation. Samoa’s recent offer to relocate the university’s main campus and headquarters to the Polynesian state may be a reminder to the Fijian government that other options are available than simply accepting interference in the USP’s governance. In any case, a decentralisation of the highly centralised Fiji-based university structure might be on the cards. It remains to be seen what impact such scenarios, coupled with the twin responsibility of serving as this year’s PIF chair and organising a successful golden anniversary summit later in the year, will have on the Fijian government. Clearly, the current USP crisis can only be resolved if Fiji works with the university’s council, composed of representatives of PIF member states, and not against it. If the crisis is allowed to fester it will also severely – if not fatally – damage the university’s reputation as an employer able to attract talent from both the region and beyond. The USP, the “jewel of Pacific regionalism” (Howes and Sen 2021) which has enabled an affordable tertiary education to so many Pacific Islanders, would no longer shine.

Policy Implications

A cohesive and comprehensive Pacific Islands Forum that can speak for the region on important issues, including global ones such as ocean governance and climate change, is a valuable partner for the EU. The latter has already communicated its interest in a “united, inclusive and balanced” PIF (EEAS 2021). Other PIF dialogue partners – such as Japan, the UK, and the US – should be encouraged to follow suit. To deepen engagement between the EU and PIF member states (and with other dialogue and development partners), high-level EU participation at the next PIF summit – for example by the Commissioner for International Partnerships – would be useful. Furthermore, the planned EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific should pay sufficient attention to working with the Pacific region and its premier regional organisation, the PIF.

Closer engagement with the region should also entail intensified political and strategic dialogue. Whereas such dialogue with Australia and NZ on the region is important in its own right, it cannot replace relevant dialogue with the region itself. Finally, the EU member states that have already issued Indo-Pacific strategies or policy papers (France, Germany, and the Netherlands) should make sure that their support for the Pacific region – in terms of development cooperation and beyond – aligns with the expressed ambitions. More concretely, the announced closure of the Pacific office of the Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) is a step in the wrong direction.

Footnotes

References

Beck, Collin (2020), Geopolitics of the Pacific Islands: How Should the Pacific Islands States Advance Their Strategic and Security Interests?, in: Security Challenges, 16, 1, 11–16.

CartoGIS Services (2020), Subregions of Oceania, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, https://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/mapsonline/base-maps/subregions-oceania# (12 April 2021).

Dayant, Alexandre (2021), Pacific Development Outlook for 2021, in: The Interpreter, 8 February, www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/pacific-development-outlook-2021 (19 March 2021).

EEAS (European External Action Service) (2021), Local EU Statement on the Decision of Five Micronesian States to Initiate the Process of Withdrawal from the Pacific Islands Forum, 12 March, https://eeas.europa.eu/regions/pacific/94819/local-eu-statement-decision-five-micronesian-states-initiate-process-withdraw al-pacific_en (24 March 2021).

Fry, Greg (2021), The Pacific Islands Forum Split: Possibilities for Pacific Diplomacy, DevPol Blog, 23 February, https://devpolicy.org/the-pacific-islands-forum-split-possibilities-for-pacific-diplomacy-20210223/ (26 February 2021).

Fry, Greg (2019), Framing the Islands: Power and Diplomatic Agency in Pacific Regionalism, Canberra: ANU Press, https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n6014/pdf/book.pdf (22 February 2021).

Howes, Stephen, and Sandhana Sen (2021), Pacific Regionalism in Crisis: Forum and USP Both Weakened in a Single Day, DevPolicy Blog, 5 February, https://devpolicy.org/pacific-regionalism-in-crisis-forum-and-usp-both-weakened-in-a-single-day-20210205/ (15 February 2021).

Köllner, Patrick (2020), Australia and New Zealand Face Up to China in the South Pacific, GIGA Focus Asia, 3, July, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/20031118-australia-new-zealand-face-china-south-pacific/ (16 March 2021).

Morgan, Wesley (2020), Oceans Apart? Considering the Indo-Pacific and the Blue Pacific, in: Security Challenges, 16, 1, 44–64.

Pryke, Jonathan (2021), What Next for Pacific Regionalism?, in: The Interpreter, 10 February, www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/what-next-pacific-regionalism (15 February 2021).

Ratuva, Steven, and Katerina Teaiwa (2021), Op-Ed: Pacific Regionalism on Trial: A Way Forward, Pacific Islands News Association, 2 March, www.pina.com.fj/?p=pacnews&m=read&o=1588815404603d99d7cc2a8b379396 (2 March 2021).

Sen, Sadhana (2020), The Pacific Islands Forum Leadership: Who and For What?, DevPolicy Blog, 12 November, https://devpolicy.org/the-pacific-islands-forum-leadership-who-and-for-what-20201112/ (22 February 2021).

Tukuitonga, Collin (2021), Dual Crisis at USP and the Pacific Islands Forum: The Chance For a Different Future?, DevPolicy Blog, 8 February, https://devpolicy.org/dual-crises-at-usp-and-the-pacific-islands-forum-the-chance-for-a-different-future-20200208-2/ (15 February 2021).

Wallis, Joanne, and Michael Wesley (2016), Unipolar Anxieties: Australia’s Melanesia Policy after the Age of Intervention, in: Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 3, 1, 26–37.

Wyeth, Grant, and Larissa Stünkel (2021), First Fiji, Then the World, in: Foreign Policy, 15 February, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/02/15/first-fiji-then-the-world/ (20 March 2021).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Asia

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Asia

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Köllner, Patrick (2021), "Micronexit" Overshadows Golden Anniversary of the Pacific Islands Forum, GIGA Focus Asia, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-72475-7

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.