- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Mind the Gap! Comparing Gender Politics in Japan and Taiwan

GIGA Focus Asia

Mind the Gap! Comparing Gender Politics in Japan and Taiwan

Number 5 | 2018 | ISSN: 1862-359X

Japan and Taiwan share common cultural characteristics, and their economics have developed in similar ways too. They perform equally well on educational attainment, infant mortality, and unemployment meanwhile. Yet, Japan lags far behind Taiwan when it comes to gender equality – including the significantly less prominent and active role of women in parliament in the former. The difference between the two countries in this regard can be explained by three key political factors.

First, women’s movements in Taiwan benefitted from the momentum created during the democratisation phase of the early 1990s. They have since become a powerful force, pushing for gender equality measures such as mandatory gender quotas. In contrast, women’s movements in Japan tend to be fragmented, decentralised, or focussed only on specific issues.

Second, the major center-right Kuomintang party in Taiwan has actively taken advantage of gender equality issues for electoral purposes. By contrast, in Japan the move towards greater gender equality has faced a strong backlash from various conservative forces ranging from the ruling center-right Liberal Democratic Party to right-leaning media, or even to conservative female academics.

Third, the Japanese political system makes it harder to promote gender issues there compared to in the Taiwanese case. Japan’s parliamentary system marginalises the role of legislators, which in turn limits female parliamentarians’ efforts. Also, even if both countries have two electoral “tiers” – one to represent the district, and the other that of the political party – the latter one in Japan features a loophole, and thus has not been used to represent diverse interests within society.

Policy Implications

As the comparison shows, politics has played a significant role in creating a gap in the two countries’ gender balances. Considering that Japan has continued to be highly self-conscious about its international standing, there should be constant external pressure for women’s political empowerment, career advancement, and better work–life balance. Corrective measures could include the adoption of a gender quota in politics and business, or more incentives for both men and women to take parental leave.

Gender Gap in Politics: Women’s Presence in Parliament

Japan and Taiwan are two advanced democracies in East Asia both well known for their significant progress across various dimensions of human development. For instance, according to the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) – which includes statistics on life expectancy, education, and income per capita – both Japan and Taiwan are categorised as “very high human development” countries. They ranked 20th and 21st worldwide in 2014, respectively.

Shifting our attention to gender promotion, newspaper headlines often give an impression of the two countries’ similar degrees of advancement. In Japan, often dubbed the man behind the country’s “Womenomics” campaign, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has positioned himself as a passionate advocate of gender equality by promoting women’s participation in the workforce. Moreover, in addition to becoming the first elected female governor of Tokyo in 2016, Yuriko Koike challenged Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in May 2017 by creating a new party ahead of the general election of that year.

In Taiwan, meanwhile, Tsai Ing-wen became the first female president in 2016 and was chosen by Forbes magazine as one of the world’s three most powerful female politicians alongside the German chancellor and the British prime minister in 2017. Despite the surface-level similarities, however, the levels of gender equality vary dramatically between the two countries. For instance, based on sub-indexes such as political empowerment or economic opportunity, the Gender Inequality Index (GII) by the UNDP and the Gender Gap Index (GGI) by the World Economic Forum both capture a substantial difference existing in women’s status in each country – Taiwan and Japan were ranked 5th and 22nd worldwide in 2014 by the GII, and 38th and 111th in 2016 by the GGI.

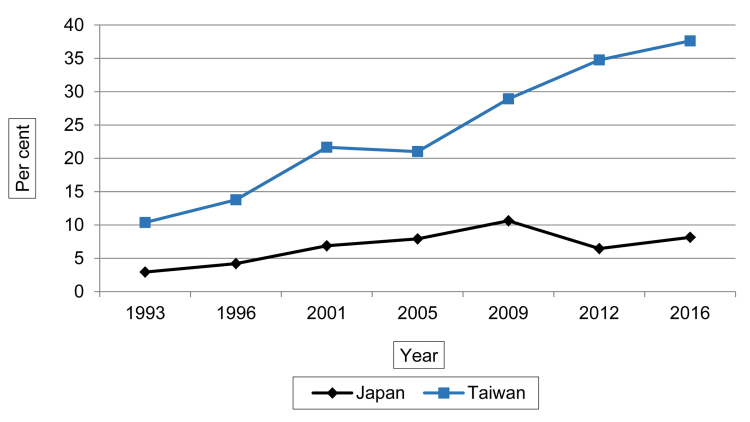

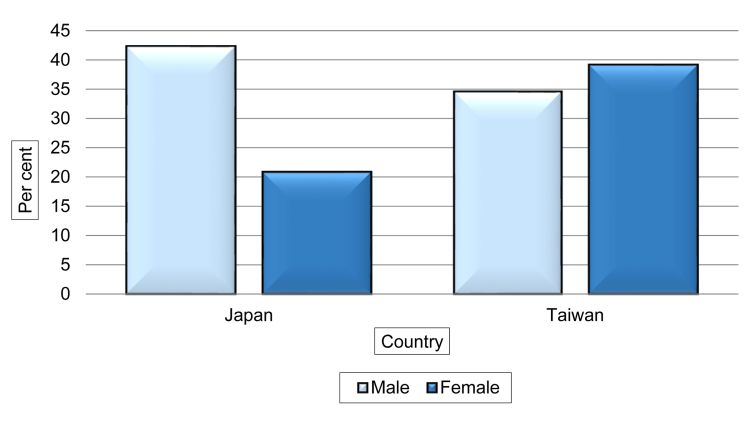

Among other things, Figures 1 and 2 below clearly show the gap in women’s political empowerment between the two countries. As for the presence of female legislators in parliament, Taiwan saw a significant increase therein between 1992 and 2016, moving from 10 per cent to 38 per cent; the equivalent figure for the lower house in Japan stayed between 5 and 10 per cent, meanwhile. Further, in contrast to Taiwanese female candidates’ equally strong success rate in elections (calculated by dividing the number of elected legislators by the number of candidates) compared to their male counterparts, Japanese female candidates fared twice as unfavourably during the observed period.

This gap is problematic because empirical works drawn from various world regions show that when there are a higher number of female legislators, they are more likely to voice concerns about women’s issues and ultimately produce relevant political results. That is, the presence of women in public office has the potential to transform representation by reflecting women, their lives, and their perspectives in the policymaking process – which in turn increases government responsiveness to women’s needs, interests, and views (Burrell 2006). Taiwan is no exception in this regard, since many female legislators have been at the centre of important legislative changes there. These include measures such as financial loans to domestic violence victims, protecting mothers’ right to breastfeed in public areas by setting up relevant public facilities, or extending the number of days of paid parental leave.

Considering that these two developed East Asian democracies share several important characteristics – including roots in Confucianism, similar economic and social developmental paths, a lack of strong trade union and leftist parties, and the legacies of one-party dominance until two decades ago – the apparent gender gap appears to be a puzzle. Although the earlier gap can be explained by Taiwan’s introduction of reserved seats for women (enshrined in the 1946 constitution), the widening differences in the past two-and-a-half decades are found to stem from three key political barriers that Japanese female legislators have faced. The following sections will analyse each of these barriers, and thereafter a discussion of the implications for Japanese and Western policymakers will ensue.

Democratisation and Women’s Movements

A plethora of empirical works have repeatedly demonstrated that, in addition to committed political parties, women’s movements led by related organisations are crucial to advancing gender issues. In this regard, Taiwan has had in place much more favourable conditions since the early 1990s than Japan has. Riding on the wave of momentum created by the democratisation trend that first started in the late 1980s, women’s organisations have been a powerful force behind gender politics in Taiwan (Clark and Lee 2000). To begin with, the diversity and the number of feminist groups increased dramatically after the lifting of martial law in 1987 (Clark and Clark 2008). Another crucial moment that led to the mainstreaming of gender issues came at the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women, which was held in Beijing in 1995 and attended by 40,000 non-governmental organisation (NGO) and 181 state representatives. The conference set in place 12 action plans to further women’s rights, and spurred transnational information-sharing on quotas via academic networks and personal contacts between female bureaucrats, feminist politicians, and women’s movements.

Although Taiwan was unable to participate in the 1995 Beijing conference as an independent country, it was still affected through various feminist channels (a good example is that of United States feminist Jo Freeman, who insisted on the importance of the number of women reaching one-quarter of total members so as to have a substantial impact within any organisation). As a result, feminist activists attempted to increase the number of reserved seats for elections at all levels and a strong women’s group – The Awakening Foundation – pressured the prime minister to convene the Commission for the Promotion of Women’s Rights in 1995. With respect to other key legislative changes, activists helped bring about ones in the late 1990s that made divorce law and parenting law more women-friendly – and also helped secure the provision of parental leave and childcare facilities for employees in 2002 and 2007, respectively. In the second decade of this century, meanwhile, women’s rights advocates in Taiwan have closely monitored and reviewed laws and administrative measures that go against the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

Despite Japan’s longer history of women’s movements, beginning with the suffragettes in the 1930s, women’s organisations have played only a relatively marginal role in promoting gender equality as compared to in Taiwan. As often noted by students of Japanese gender politics (Gelb 2003; Gaunder 2015; Dalton 2015), women’s movements in Japan can be characterised as fragmented, decentralised, single-issue focussed, and/or short-lived. And oftentimes their primary interests – for example, with the Housewives Association (Shufuren) – never lay in securing equal rights and opportunities for working women but rather with protecting consumer rights and preventing environmental pollution instead (McKean 1993). Although women’s organisations have played a crucial role in issues such as the banning of prostitution or the advancement of abortion rights, they never went as far as becoming a unified and consistent political force pushing for women’s political empowerment on the back of a mandatory gender quota.

So, why has Japan lacked large-scale, nationwide umbrella women’s organisations or a broad coalition of groups with ambitions encompassing feminist goals? Despite the lack of systematic research hereon to date, two potential reasons can be pointed out. First, Japanese social movements in general have not had an opportunity to politicise issues through a democratisation movement; women’s issues are no exception to this. This is a huge contrast to Taiwan, where social movements have been politicised through various advocacy NGOs since multiparty competition began in earnest in the early 1990s.

Second, there is a marked difference in the intersection of gender issues with key political cleavages. In both countries, nationalistic issues emerged as significant ideological divisions between left and right during the democratic transition period. Taking either a diplomatic or military stance towards mainland China has been the core cleavage in Taiwan, while in Japan the primary political divide has been on the recognition of its wartime crimes and on the approval or rejection of the country’s peace constitution Article 9 (which renounces Japan’s right to wage war). Unlike Taiwan, where the core aspects of gender promotion never overlap with the country’s key political dividing line, feminist movements by their very nature in Japan often go against what right-wing forces stand for. A clear example can be found in the strong reactions to feminists trying to politicise the issue of the comfort women exploited and sexually abused by the Japanese occupiers during World War II. This is similar to women’s health concerns such as breast cancer or osteoporosis in the US, which can run the risk of becoming highly contested healthcare issues – or, alternatively, women’s reproductive rights potentially overlapping with conflictual religious cleavages in Latin America.

Partisan Bias on Gender Promotion

In light of the previous scholarship, the ideological spectrum of the incumbent government is often identified as a crucial factor affecting gender promotion. Several empirical works have pointed out the effect of partisan bias: there is a noticeable difference between left-wing and right-wing governments (Swers 2013). The key point of these works is that women’s issues tend to be better represented under left-wing governments, who often emphasise progressive values such as inclusiveness, diversity, and equality.

In this regard, there seems to be no clear partisan bias on gender issues in Taiwan. It was the centre-right Kuomintang (KMT) party that adopted reserved seats for women in the 1946 constitution. Moreover, the adoption of party-level gender quotas at the turn of the twenty-first century is another clear example indicating minimal division between key Taiwanese political parties on gender issues. Initially adopted by the centre-left Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 1996 as a 25 per cent quota for women candidates, the KMT followed in its footsteps in the year 2000 – both parties eventually agreed to put in place the 50 per cent nomination rule (at the party level) during the 2005 constitutional reform, meanwhile.

Beyond these quota-related developments, there are other pieces of evidence supporting the notion that the KMT is not an anti-gender-promotion party. For instance, in 2004 several legislators from the center-right Pan-Blue coalition – consisting of the KMT, the People First Party, and the New Party – formed the Female Legislators Alliance to promote women’s welfare in the Legislative Yuan. Also, the KMT elected Hung Hsiu-chu as the first chairwoman of the party in 2016. Moreover, even when it comes to sponsoring important bills promoting women’s interests, the KMT did not lag behind the centre-left DPP at any point between 1992 and 2016 (Shim 2016b).

Unlike Taiwan, gender-promotion efforts regarding work–life balance, equal employment and promotion, and domestic violence have met with a marked backlash on various fronts in Japan. To begin with, the long-ruling LDP is known for its anti-women stance. Reflected in its last-place rank among major political parties in Japan regarding the proportion of female legislators it counts among its numbers, the LDP is known for opposing the introduction of any kind of gender quota on the grounds that it could be a form of “reverse discrimination” (Yoshida 1999: 61). Going further, right-wing male politicians have also been outspoken in their denigration of gender issues – like, for example, Masakuni Murakami (a former Diet member), who once equated “gender equality” with being a communist idea and criticised its alleged challenge to traditional family values (Gelb 2003). Conservative press outlets like Yomiuri and Sankei have echoed this sentiment, and “gender equality issues” have often come under attack from ultra-right wing groups such as the Nihon Kaigi – whose credo is “going back to the pre-war structure” (Hayashi 2000).

Beyond the “usual suspects,” the conservative influence stemming from certain women themselves was also not negligible however. Female academics such as Hasegawa Michiko, who advocates the traditional male-breadwinner model, have played a significant role in advancing the conservative agenda – particularly by attacking basic gender equality law (Osawa 2015). Furthermore, in the early years of the new century, conservative women’s groups – for example the Japanese Women’s Association (Nippon Josei no Kai) – actively engaged in public and political campaigns to defend a woman’s role as wife and against feminist ideas (Osawa 2015). To make matters worse, even the centre-left Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) did not actively push the gender issue to the forefront of politics when it was in government. Empirical works on gender politics show that the adoption of a gender quota in the legislature tends to be taken up by imitation by leftist parties across countries, and then either becomes law or further support follows from other key parties (Caul 2001). Japan goes against this trend, since the DPJ never adopted a party-level gender quota even during the period of its stable majority rule (2009–2011).

Constraining Political Institutions

For countries like Japan lacking both a strong social-democratic party and unified women’s interest groups, having a presidential structure could have provided a channel through which entrepreneur legislators actively promote women’s issues. Because legislators’ independence is guaranteed for a fixed term within this structure, higher levels of legislative activism by individual legislators have been reported in presidential democracies than in parliamentary ones (Olson and Mezey 1991). Taiwan is not an exception to this general pattern, where each legislator perceives himself or herself as an independent law-making institution (Shim 2016a). Reflecting this, Taiwanese legislators are much more likely to deviate from the party line, are better resourced with more full-time staff, and also each sponsor a substantially higher number of bills.

Considering that many of the articulated gender issues resonate well with the public (such as fixed parental leave or childcare benefits), active engagement with these matters can be a particularly tempting choice. This is specifically true for newly elected legislators, ones without a strong political base such as organised support groups or local constituents, or those who have fought for equality before. Reflecting this, based on my own calculations, more than 90 per cent of all bills related to gender promotion (concerning such issues as abortion rights, maternity leave, subsidies for mothers, domestic violence, workplace/employment discrimination, female career advancement, maternal healthcare, long-term care for the elderly, and childcare) are submitted by legislators in Taiwan – particularly by newly elected ones with a civil society background – while the equivalent figure was less than 50 per cent thereof for Japan between 1992 and 2016. This gap appears even starker when comparing the average number of bills concerning women’s interests supported per legislator – more than 20 times higher in Taiwan than in Japan.

In addition to the limited initiatives by female legislators in Japan under parliamentary rule, an institutional loophole in that country’s new electoral rules blocks another potential avenue for gender promotion. Both Japan and Taiwan changed to two-tiered electoral systems (where voters now cast two votes: one for a district-level candidate, and one for a party-level one – but, at the same time, without any linkages between the two tiers in allocating total seats) in 1994 and 2005, respectively. Under the new system, the party tier is designed to serve nationwide interests. In the case of Taiwan, it has indeed fulfilled that function since the KMT and DPP have nominated a wide array of national-level specialists or representatives – for example, child experts, nurses, doctors, the disabled, or those working for NGOs. On the contrary, Japan allows the same candidate to be listed at both the district and party tiers and has used the latter to revive the “best-placed losers” from the district tier. In other words, even if a candidate did not win in the district that they ran in they can still be elected at the party tier if the vote number gap left them close to the winner as compared to the other candidates.

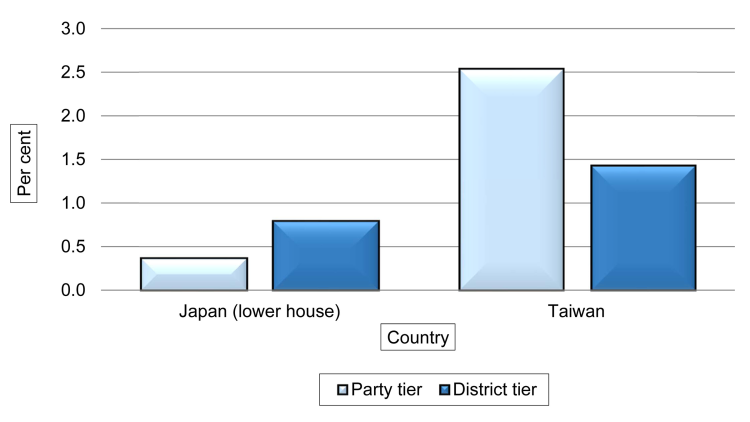

And, in fact, roughly 60 per cent of elected Japanese candidates at the lower house party tier have been elected this way since the electoral reform of 1996. This rule has incentivised candidates to be district-oriented, and has specifically disadvantaged female candidates in Japan for the following reasons: Preparing to be a district-tier legislator is not favourable for female candidates, because it necessitates a substantial amount of constituency face time through presenting oneself physically in person (Miura, Shin, and Steele 2018). For female candidates who have family obligations outside of work, this poses a significant barrier. Moreover, after being elected, maintaining one’s district requires legislators to build local-level networks through sports clubs, alumni associations, or personal political apparatus, leaving little time to design and promote policies with nationwide implications like gender promotion. As presented in Figure 3 below, the evidence clearly supports this: when it comes to promoting gender issues through sponsoring related bills, party-tier legislators in Taiwan are 70–80 per cent more likely to back gender issue bills than their district-elected counterparts are. In contrast to this, both party- and district-tier legislators in the Japanese lower house almost entirely disregard gender issues – and there is no tangible difference between the two on this.

How Should Europe Facilitate Gender Promotion in Japan?

Looking back, most of the drivers of gender promotion in Japan came from external factors and for instrumental reasons. For instance, corruption scandals such as the Recruit Scandal led to the “Madonna Boom” in the 1989 upper house election – large numbers of female candidates were thereafter fielded by the Social Democratic Party of Japan with success. Similarly, cut-throat political competition in the first decade of this century led to the nomination of several female candidates by Junichiro Koizumi in 2005 and Ichirō Ozawa in 2009 – often labelled as “Koizumi Children and Ozawa Children,” respectively. Moreover, Prime Minister Abe’s Womenomics is designed to solve low fertility and ageing society problems by tapping into a “underutilised resource” – thus furthering economic growth.

As can be seen from its high levels of UN budget contribution (the second-highest of any country in the world), Japan remains acutely self-conscious about its international standing. That is, the country’s policymakers and opinion leaders have long shown an active interest in maintaining its place in international society in addition to preoccupying themselves with whether Japan is meeting international standards. Considering the rising number of foreigners visiting Japan – according to the Japan National Tourism Organization, the number thereof increased from 8.4 million in 2012 to 28.7 million in 2017 – it is high time for European policymakers to politicise the issue of promoting gender equality by exerting strong pressure from outside.

In this sense, events such as the fifth annual World Assembly for Women! (WAW!) meeting in Tokyo, scheduled to be held in March 2019, can serve as an invaluable opportunity – one that will bring together representatives from all over the world. The pressure applied should materialise beyond mere rhetoric, given the previous tendency of overpromising and under-delivering in Japan. During speeches given at the UN General Assembly in September 2013 and the World Economic Forum in January 2014, for instance, Prime Minister Abe emphasised the need to incorporate women into Japan’s workforce – and started his 2014 cabinet with the highest-ever number of female ministers included (7 out of 18). However, today the number thereof has dropped to just one with his recent cabinet reshuffle; unsurprisingly, so did Japan’s gender gap ranking in 2017 too (114th out of 144 countries). Also, we should bear in mind that most of the female politicians who entered into politics as a result of the external factors/instrumental reasons specified above ultimately faded into the background rather quickly.

Therefore, external pressure regarding gender promotion in Japan should go beyond measures for achieving only temporary window dressing; it should rather be about making concrete attempts to institutionalise this issue area in the long term. As for the political empowerment of women in Japan, there should be clear pressure from European policymakers for the adoption of mandatory gender quotas at both the local and national levels. Given the two-tiered electoral system of Japan, at least half of party-level nominations should include female candidates. This means closing the current electoral loophole in the lower house party tier, which allows the dual nomination of district-tier candidates, as well as shifting the whole incentive structure so as to attract female candidates who can promote nationwide interests – similar to in Taiwan.

In addition, there should be clear measures in place on women’s career advancement and work–life balance within the private sector. When Womenomics was at its peak in 2014, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare earmarked some JPY 120 million (EUR 940,000) in subsidies for companies hiring women for managerial positions – but ended up receiving zero applications. In a similar vein, although a generous 12-month paternity leave period exists by law in Japan, the take-up rate of it is only 2–3 per cent (OECD 2016). Given Japan’s male-oriented work culture, mere recommendations or weak incentives are not expected to bear much fruit. What should be pushed by European policymakers is, rather, either legalising gender-promotion measures, enforcing strict penalties for not applying them, or creating stronger incentives – as applied in other countries. For instance, similar to the schemes applied in the Nordic countries, Japan could make paternity leave mandatory for a family to be eligible for the full amount of parental leave benefits available to both parents combined. Considering the potential burden this could cause to small enterprises, these measures might first be applied to firms with a large number of employees (say 300 to 500).

Despite its slow progress in the advancement of gender equality, we should not forget that Japan is one of the countries that went through the fastest modernisation process of the late nineteenth century. With the right amount of nudging from outside, Japan hopefully will be able to internalise the significance of gender promotion and spearhead the progress among other Asian countries too – just like it once did with its economic development.

Footnotes

References

Burrell, Barbara (2006), Looking for Gender in Women’s Campaigns for National Office in 2004 and Beyond: In What Ways Is Gender Still a Factor?, in: Politics and Gender, 2, 3, 354–362.

Caul, Miki (2001), Political Parties and the Adoption of Candidate Gender Quotas: A Cross-National Analysis, in: Journal of Politics, 63, 4, 1214–1229.

Clark, Cal, and Janet Clark (2008), Institutions and Gender Empowerment in Taiwan, in: Kartik Roy, Hans Blomqvist, and Cal Clark (eds), Institutions and Gender Empowerment in the Global Economy, World Scientific Studies in International Economics, 5, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 131–150.

Clark, Cal, and Rose J. Lee (2000), Democracy and “Softening” Society, in: Rose J. Lee and Cal Clark (eds), Democracy and the Status of Women in East Asia, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 185–192.

Dalton, Emma (2015), Women and Politics in Contemporary Japan, Abingdon, OX, New York, NY: Routledge.

Gaunder, Alisa (2015), Quota Nonadoption in Japan: The Role of the Women’s Movement and the Opposition, in: Politics and Gender, 11, 1, 176–186.

Gelb, Joyce (2003), Gender Policies in Japan and the United States: Comparing Women’s Movements, Rights and Politics, Heidelberg: Springer Nature.

Hayashi, Michiyoshi (2000), Fashizumuka suru feminizumu (Fascism-Turning-Feminism), in: Shokun, 7, 88–98.

Legislative Yuan (n.d. a), Legislative Yuan, Republic of China (Taiwan), www.ly.gov.tw (11 July 2018).

Legislative Yuan (n.d. b), Legislation Search, http://lis.ly.gov.tw/lgcgi/lglaw (11 July 2018).

McKean, Margaret (1993), Equality, in: Takeshi Ishida and Ellis Krauss, Democracy in Japan, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 201–224.

Miura, Mari, Kiyoung Shin, and Jackie F. Steele (2018), Does “Constituency Facetime” Reproduce Male Dominance? Insights from Japan’s Mixed-Member Majoritarian Electoral System, paper presented at the 2018 International Political Science Association Meeting, Brisbane, Australia.

National Diet Library (n.d.), Legislation Search, http://hourei.ndl.go.jp/SearchSys/ (19 September 2018).

OECD (2016), OECD Statistics on Employment: Length of Maternity Leave, Parental Leave, and Paid Father-Specific Leave, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54760 (19 September 2018).

Olson, David M., and Michael L. Mezey (1991), Legislatures in the Policy Process: The Dilemmas of Economic Policy, 8, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Osawa, Kimiko (2015), Traditional Gender Norms and Women’s Political Participation: How Conservative Women Engage in Political Activism in Japan, in: Social Science Japan Journal, 18, 1, 45–61.

Shim, Jaemin (2016a), Welfare Politics in Northeast Asia: An Analysis of Welfare Legislation Patterns in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, PhD Dissertation, Oxford: University of Oxford.

Shim, Jaemin (2016b), Gender and Politics in Northeast Asia: Legislative Patterns and Performance of Female Legislators in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, paper presented at the 6th European Political Science Association, Annual General Conference, Brussels, Belgium (23–25 June).

Smith, Daniel M., and Steven R. Reed (2017), The Reed-Smith Japanese House of Representatives Elections Dataset, Harvard Dataverse, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/QFEPXD (19 September 2018).

Swers, Michele L. (2013), Women in the Club: Gender and Policy Making in the Senate, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Yoshida, Rie (1999), CHEER UP! – Josei to Seiji no Ii Kankei (Cheer up! Good Relations between Women and Politics), Tokyo: Kindai Bungeisha.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Asia

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Asia

Regional Institutes

How to cite this article

Shim, Jaemin (2018), Mind the Gap! Comparing Gender Politics in Japan and Taiwan, GIGA Focus Asia, 5, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-60540-9

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.