In Brief | 29/01/2015

LGBT Rights Are Not Politically Sensitive in Vietnam

Vietnam has abolished the ban on same-sex marriage – an unusual step in the region.

Vietnam’s National Assembly has made national history by enshrining into law provisions that acknowledge the existence of gay couples. The revised law has been in effect since January 2015. Although the government withdrew an option on full equality , the National Assembly has removed its ban on gay marriage.

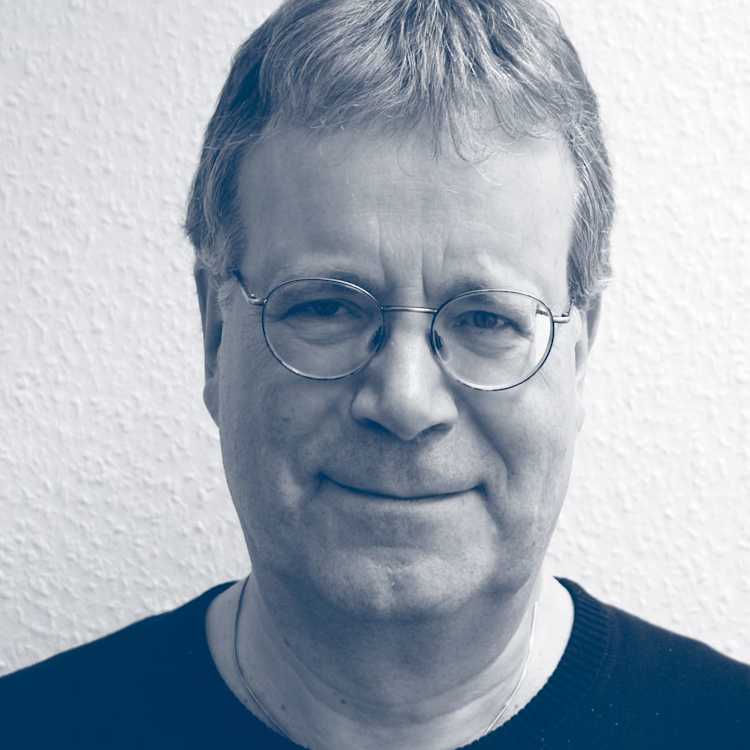

Dr. Jörg Wischermann, what does this say about Vietnam in the context of the region, where some countries, such as Singapore, continue to ban gay marriage and even gay behavior?

Jörg Wischermann: Vietnam is following a worldwide trend to give lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people the same rights heterosexual people and couples enjoy. But Vietnam is not the attraction that Singapore and Thailand – for example, Bangkok – are for LGBT people. Among other things, this might have to do with the fact that Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City still lack the infrastructure the LGBT community creates, likes and attracts (clubs, bars, salons, theatres, cinemas, etc.).

Moreover, Vietnam’s national and local governments do not seem to have recognized what Singapore’s government once realized: LGBT tourists are more often than not affluent people who spend a lot of money per day. But it might also be that Vietnam’s bad reputation in terms of human rights – that is, the absence of a "Rechtsstaat" (meaning that there is no rule of law) – makes LGBT people think twice before travelling to Vietnam.

Without a doubt Vietnam’s new law is something extraordinary in a region where many countries have deeply conservative societies and where many governments do not dare to give LGBT people the same rights heterosexual people enjoy, for religious or other reasons. But here one must keep in mind that Vietnam’s government didn’t embark on this path just because there was considerable pressure from local NGOs, local LGBT organizing rallies, etc.

Probably much more important was that in 2013 the communist government wanted to get a seat on the UN Human Rights Council (which it finally got) and urgently needed to do something to counter Vietnam’s extremely bad human rights record. As Human Rights Watch recently stated, in 2014 at least 29 activists and bloggers were sentenced to many years in prison for national-security-related crimes such as abusing the rights to freedom and democracy to infringe upon the interests of the state or undermining national unity policy.

In the same year, more than a dozen critics were arrested. Human Rights Watch estimates that 150 to 200 activists and bloggers are serving prison time in Vietnam simply for exercising their basic rights. Paris-based freedom watchdog Reporters Without Borders, which lists Vietnam as an "Enemy of the Internet," ranked the country 174th out of 180 nations in its press freedom index for 2014.

Hence, in the eyes of the Vietnamese government something had to be done and was done: lifting the ban on same-sex marriage, since this was, as one NGO director told me, "politically not sensitive". This is important to note: LGBT issues, including the issue of equal rights, are not seen by those in power as endangering the Vietnam Communist Party’s rule and the government’s position. Those in power could afford those steps without any risk in terms of their political rule.

The revised law on marriage and family without doubt indicates some progress in terms of recognition of people who in the eyes of some Vietnamese seem to be "different". This is a process which started in 2005/06 and is taking place in the context of Vietnam’s effort to prevent the further spread of HIV/AIDS. It has included a 2008 law which bans discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS and which was accompanied by the officially acknowledged formation of various new groups and new country-wide networks of people active in the field of HIV/AIDS prevention and care.

A broad ideological framework on human rights and gender equity has enabled the collaboration of LGBT groups with a wide range of Vietnamese civil society organizations, which have carefully avoided open confrontation with those in power.

It seems that a social movement to accept same-sex marriage has arisen in Vietnam. Is that unusual?

Wischermann: I would not call those various Vietnamese NGOs, groups, networks, etc. a social movement. Social movements aim to achieve societal and/or political change. Vietnamese NGOs, groups, networks, etc. engaged in this policy field ask for recognition of LGBT people and that LGBT people can enjoy the same rights heterosexual people have (e.g. the right to adopt children).

Vietnamese LGBT people want to have equal rights to heterosexual people and be respected like other people, and they aim for changes in laws and societal attitudes. One could even say that those in favor of same-sex marriage do what religious conservatives (at least in the US and elsewhere) have long begged them to do: they embrace family values.

But those engaged in this policy field in Vietnam do not intend to achieve, and do not realize, political change in terms of political structures and the power monopoly of the Vietnamese Communist Party. And one should not forget the deeply conservative Vietnamese society.

There might have been some changes in this society towards a more liberal stance vis-à-vis LGBT people, but my guess would be that many people in Vietnamese society (especially in the North) do not see LGBTs as "normal" people. You can bring your partner to your parent’s home in Vietnam, but you should not talk with your mother about the nature of your relationship.

What does this say about civil society in Vietnam?

Wischermann: A lot. First, civil society in Vietnam is under strong pressure from the Vietnamese Communist Party and the state. The latter control at least the mass organizations, most if not all professional organizations, and the business organizations. Thus, they control the important segments of civil society. The party and state also influence NGOs’ and faith-based organizations’ activities and organizing, and their relationships with a certain social clientele. Vietnamese civil society’s room to maneuver is limited.

Second, many if not all organizations primarily want to change the society, some want only to change Vietnamese society, and many keep away from "chinh tri" (party politics). One could even assume that most if not all organizations do not intend to achieve fundamental political change. They have this in common with many civil society organizations in Eastern Europe before 1989. As Vaclav Havel once put it, "The primary purpose of the outward direction of these movements is always to have an impact on society, not to affect the power structure, at least not directly and immediately."

Do you think this is something of a human rights win for Vietnam?

Wischermann: Within certain limits and to a certain extent, yes. However, the fact remains that there are hundreds of prisoners of conscience in Vietnam, and bloggers and social activists are often harassed, with the state threatening to put them in prison for long terms.

Interview: GIGA