- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Beyond the Model Reform Image: Morocco’s Politics of Elite Co-Optation

GIGA Focus Middle East

Beyond the Model Reform Image: Morocco’s Politics of Elite Co-Optation

Number 3 | 2018 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Since coming to power in 1999, Morocco’s King Mohamed VI has strengthened his rule by reinforcing his father’s strategy of elite co-optation and rotation. However, after two decades of economic predation, the gradual waning of rent-distribution channels, and the lack of genuine democratisation, the king’s strategy of power consolidation may be running out of steam.

Mohamed VI’s rule has coincided with the adoption of large-scale neo-liberal reforms, which have created new opportunities for economic co-optation and strengthened the monarchy’s alliance with local economic and political elites. However, this neo-liberal turn has come with important costs for low-income groups.

The last 20 years have been marked by an increase in the obedience of the local elite and the weakening of formal channels of political participation. The king has also been able to take credit for successful policies while simultaneously blaming the administration or elected officials for failed ones and contributing to the de-institutionalisation of the country’s politics.

Increased inequality and an established culture of contempt towards the “losers” of liberalisation and privatisation policies mean that those dissatisfied with the regime will increasingly turn to coping mechanisms that have a direct impact on European security (e.g. drug and human trafficking, international terrorism, and violent political contestation).

Policy Implications

A stable and prosperous Morocco is vital to Europe’s security. However, inclusive and sustainable economic growth is only possible if genuine democratic reform allows for effective implementation of the rule of law, respect for human rights, and the development of robust democratic participatory channels through which popular grievances can be addressed.

Elite Co-Optation through Neo-Liberalism

As with other authoritarian regimes, the Moroccan palace has long been aware that elite opposition rather than mass-based opposition represents the most serious political danger. All three Moroccan kings who have ruled the country since independence in 1956 have thus used two main instruments to pre-empt mobilisation: carefully timed policy concessions on the one hand, and the active co-optation of potential challengers on the other. While policy concessions have often been symbolic and have never significantly weakened the king’s prerogatives, the Moroccan palace has been able to create a relationship of dependence with most of the country’s economic, political, and cultural elite – who have traded their loyalty for privileged access to the state’s rent distribution channels.

While the logic of economic co-optation was a constant feature of Moroccan politics under Mohamed V (who rewarded loyalist rural elites with access to state rent channels in exchange for their support during his struggle with the nationalists) and later Hassan II (who used the same strategy to reward loyalist leftist parties who supported his marginalisation of Islamic movements), King Mohamed VI currently benefits from a distinctive international economic context which has allowed him to expand the monarchy’s strategy of economic co-optation to unprecedented levels.

Whereas Mohamed V and Hassan II dispensed rent through relatively limited channels (usually in the form of transportation, fishing, or mining licenses), Mohamed VI has overseen large-scale neo-liberal reforms since 1999 – which have created new opportunities for economic co-optation – and strengthened the monarchy’s alliance with the local economic and political elites. As noted by Guazzone and Pioppi (2009: 6) and Boukhars (2011: 53), the adoption of neo-liberal policies in the form of privatisation, liberalisation, and administrative deregulation and the concomitant retreat of the state from the delivery of public goods served a double function. On the one hand, it freed the authorities from the financial burden that came with the state’s former responsibilities. On the other, it increased the resilience of the state by helping produce a new generation of business elites dependent on the state for regulation, arbitration, and access to economic opportunities. Although the king and his close associates were the main beneficiaries of the neo-liberal turn of the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century, traditional supporters of the palace, loyalist families, and most of the country’s historical opposition members also witnessed a major improvement of their economic status. For Amal, a Moroccan academic, “large parts of the economic elite are in a win-win relationship with the palace, which is involved in a number of lucrative economic activities” (Amal, personal interview, 18 May 2017). These elite know that their mere proximity to the king will translate into added economic profits, even though a minority is also dissatisfied with what seems to be unfair competition from the monarchy in certain business activities such as banking or renewable energy. For Amal, the proximity to the palace is so economically rewarding that “nowadays, it is not the regime that seeks to co-opt people but rather, people that are trying to get co-opted” (Amal, personal interview, 18 May 2017). Similarly, for Fouad Abdelmoumni, head of Transparency Morocco, the country’s economic elite are “a direct creation of the palace” (interview with F. Abdelmoumni, Rabat, 22 May 2017).

According to Ghassan Wael, a young Moroccan journalist, the “main mechanism of co-optation and therefore of political resilience in the country is the use of public policies to promote major public projects, such as electrification projects in the rural sector, real-estate development, or the automobile industry, who benefit from heavy state support” (interview with G. El Karmouni, Rabat, 18 May 2017) and whose profits are channelled by the palace and its associates. Under Mohamed VI, real estate and urban redevelopment – especially in the big cities of Casablanca, Rabat, and Tangier – have become major conduits for the clientelist networks cultivated by the king and his associates. In particular, the privatisation of communally owned land unleashed an unprecedented process of capital accumulation for the regime’s clients. Additional mechanisms of economic co-optation include the privatisation of state-owned enterprises subsequently purchased by some of the regime’s associates. The neo-liberal turn was so extensive that by 2008, 90 of the country’s biggest public companies were partially or fully privatised, with the most profitable ones privatised before 2005 (Maggi 2016: 103).

Bureaucratic duplicity between the administration and private actors is a complementary win-win mechanism through which the resources of the state are mobilised to protect specific commercial enterprises usually labelled “national champions” through fiscal and administrative exceptions and/or privileges. These so-called national champions are one of the numerous channels through which the alliance between the palace and some of the country’s economic elite is cemented. A case in point is the country’s Plan Vert project, an ambitious agricultural project which is officially designed to re-energise the country’s agricultural sector. In reality, some of the country’s best rural land was made available below market price to private actors (most close to the regime), who benefit from the government’s generous agricultural fiscal policies without being subject to any form of public oversight. Public–private partnerships in newly privatised activities such as waste collection or electricity provision are also being used to bolster local cronies who have been granted the most lucrative contracts in murky if not outright illegal conditions. Companies owned by these associates have often been allowed to operate without any supervision, all at the expense of users who were forced to pay more without any significant improvement in the quality of the services provided.

The symbiotic relationship between the economic elites and the authorities also stems from the deep dependence of the former on the latter and the relative vulnerability of Morocco’s big industrial groups to globalisation. Despite benefiting from the country’s liberalisation policies and often publicly supporting liberal policies, many of Morocco’s business elites are not able to survive without the protectionist and regulative policies of the state (Benhaddou 2009: 112–115). In the gas sector, for instance, prices have been liberalised without concomitant state control, resulting in the entire sector being managed by only 15 actors – one of whom, Aziz Akhannouch, controls roughly 30 percent of the market and is also the minister of agriculture, the head of the Rassemblement National des Indépendants (RNI, a loyalist political party) and a personal friend of the king (interview with G. Wael, Rabat, 18 May 2017). A study of the largest 344 Moroccan companies conducted by Oubenal and Zeroual in 2017 shows that, after the king and his family, the second-biggest beneficiaries of the privatisation and liberalisation policies implemented in the country in the last three decades were 150 families close to the monarchy, the most important of which are also represented in government, as well as foreign investors (Oubenal and Zeroual 2017: 137, 139, 154–155).

While hitting lower-income groups the most, the neo-liberal turn also provided access to rent channels to new groups in the emerging middle class, whose support proved critical during the tumultuous first months of the Arab uprisings. Despite the important negative consequences of privatisation and deregulation policies on the general population, additional revenues allowed the regime to buy key consti-tuencies (notably, trade unions and key groups in the public administration) during the first months of the Arab uprisings in 2011. According to a young former pro-democracy activist, as a result, “most actions initiated by local actors failed because there was no support [from local actors] and ... no transmission belt between social demands and the country’s elite, who refused to legitimise popular demands” (interview with Y. Rguig, Rabat, 20 May 2017).

Even the country’s media is deeply embedded in this clientelistic logic. In their analysis of the main shareholders in the country’s media sector, Benchenna et al. (2017: 10–11) find that, with few exceptions, Moroccan media figures are members of either the regime or the local bourgeoisie, which has benefited from the economic and political liberalisation of the last 20 years. Examples of these actors include Fahd Yata, the son of Ali Yata (a former communist opposition leader and founder of one of the country’s main economic magazines); Moulay Hafid Elalamy, the current industry and commerce minister; and Aziz Akhannouch, the current agriculture minister – all of whom own some of the country’s most renowned publications (Benchenna et al. 2017: 10-11). “(F)or these businessmen, … investing in the press sector is intended to protect their own commercial interests, to support a stable political world by using their many titles in support of political communication, and to add business competence as one of the qualities required to become an established politician” (Benchenna et al. 2017: 10).

Double-Voiced Legitimacy

Another characteristic of Mohamed VI’s power-consolidation strategy is his intense legitimacy-producing discourse in which he positions himself as the sole architect of most if not all of the county’s economic, social, and political achievements. The king is omnipresent in the country’s media coverage and constantly nourishes the impression that he is the only actor able to implement political reforms or deliver successful economic projects while blaming elected politicians and local administrators for any failures.

In the last two decades, for instance, the king has taken full credit for (i) reforming the family code and thus improving women’s rights in the country, (ii) spearheading an ambitious equity and reconciliation committee, which officially turned the page on human rights abuses committed by his father, and (iii) implementing an ambitious constitutional reform project designed to empower the country’s political institutions. At the economic level, the king has (a) led major infrastructure projects which helped quadruple the length of the country’s highway network, (b) removed the quasi-totality of Morocco’s urban slums, and (c) revitalised the core centres of the country’s major cities. The monarch has also been behind some of the country’s most popular socio-cultural projects, ranging from music festivals to religious celebrations.

However, the king’s effort to produce legitimacy is a double-voiced exercise. While some efforts genuinely attempt to address some important domestic challenges such as sub-par housing or rural electrification, their other purpose is to strengthen the alliance between the king and his cronies through a systematic logic of economic transfer. In this perspective, the political and administrative reforms implemented over the last 15 years have had few positive effects beyond those associated with the regime; they have essentially targeted the country’s economic and political elite. Although they have created the impression of democratic reform, constitutional and administrative reforms have been used in practice to depoliticise and bureaucratise the king’s former opponents by rewarding them with attractive salaries and public status (interview with G. Wael, Rabat, 18 May 2017). This intensive co-optation system is formalised partly through numerous instances of mediation created under royal impulse – notably, the Human Rights National Council (CNDH), the Council for Moroccans Residing Abroad (CCME), the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), the Central Body for the Prevention of Corruption (ICPC), and the High Council for Education. These councils and committees are all presided over or staffed by established regime associates or former opponents who accepted the offer to integrate themselves into the system and target specific constituents, such as women groups, Moroccans residing abroad, and tribal notables from the Sahara region who all share high mobilisation potential. Even though these institutions are rarely able to implement practical changes despite the hype that usually surrounds their creation, the process of elite co-optation and integration that occurs is very real and helps to neutralise vocal personalities such as Driss Benzekri, a former political prisoner who was called to serve as head of the 2004 Equity and Reconciliation Commission. Another example is Salah El Ouadie, a former political prisoner and far-leftist who served as spokesperson for the pro-monarchy Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM).

Another strategy used by the monarchy is the balancing of different administrative, economic, and military interests against each other through elite arbitration. This practice serves a double function. On the one hand, it signals to the population that the monarch is genuinely concerned about political and economic reform and attentive to his subjects’ concerns. The king has thus adopted the habit of regularly scolding administrators and elected officials for their lack of professionalism. Mohamed VI has also accustomed the country to regular bouts of royal anger during which he punishes politicians or administrators deemed incompetent by removing them from office and appearing to take personal responsibility for the prompt execution of specific projects. The palace also allows royal foundations, especially the Mohamed V Foundation for Solidarity and the Hassan II Fund for Economic and Social Solidarity, to benefit from significant public resources. Both of these institutions are publicly funded, largely unaccountable to Parliament, and fall under the authority of either members of the king’s entourage or businesspersons from the private sector (Catusse 2009: 78). While the funds are public, all the prestige of these organisations reverberates on the king, who does not allow others to appear as potential competitors.

On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, the selective use of the justice system to rule on administrative corruption, nepotism, and conflicts of interests is a complementary mechanism through which the regime generates elite loyalty while giving the illusion of democratic and judicial reform. Random anti-corruption campaigns strategically target actors deemed disloyal by the king and simultaneously allow him to bolster his role as the ultimate arbitrator of diverging political and economic interests. Transparency International ranks the country 90 out of 176 (behind Liberia, Zambia, and Lesotho for instance) and regular scandals illustrate the prevalence of corruption at all levels of society but particularly in senior administrative levels dependent on the monarchy. Examples of collusion include the allocation of public land below market price to regime associates and the acceptance of blatant conflicts of interest at all levels of business and administration. For Fouad Abdelmoumni, a Moroccan economist and general secretary of Transparency International’s Moroccan chapter, “corruption is not a marginal phenomenon ... It has been a deliberate choice to encourage criminal practices” (interview with F. Abdelmoumni, Rabat, 22 May 2018).

Repression and “State Contempt”

The king’s strategy of elite rotation and rent-sharing has had important consequences for the security configuration of the country. Given the unwillingness of most of the local political elites to challenge the king and extract policy concessions benefiting the majority, the palace can afford to ignore pressing societal grievances similar to those that led to the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions in early 2011, despite disturbing signs of popular discontent.

Due to increased corruption levels, a surge in economic inequality (now the highest in North Africa), and growing administrative and political contempt towards the victims of the country’s neo-liberal policies, among them well-educated youth, Morocco is witnessing increasingly aggressive episodes of political protest (up to 50 per day in 2014 according to one observer). Moreover, the withdrawal of the state in what one journalist calls “useful Morocco” – where most of the state resources have been redeployed in the form of public–private partnerships for the benefit of the king and his allies – explains why some of the country’s most persistent protests have occurred in largely disregarded rural or semi-rural areas, such as the Rif region (2017 and 2018), the mining city of Jerada (2018), and small periphery towns such as Sidi-Ifni, Zagora, Tinghir, or Larache.

The disconnect between the “winners” and “losers” of this economic and administrative redeployment and the inability of the latter to generate real costs for the authorities allow the monarch and his associates to continue to dismiss pressing societal demands. The regime can thus afford to punish critical journalists (most of whom are now in exile), put more limitations on freedom of association, jail human rights activists, fire public servants deemed disloyal to the monarchy, hijack the electoral process by appointing cronies to head client political parties, and engage in political pursuits against public servants who report cases of corruption involving associates of the king (interviews with K. Ryadi, Rabat, 19 May 2017 and F. Abdelmoumni, Rabat, 22 May 2017). The king, whose personal fortune has been said to amount to more than USD 2.5 billion, can even afford to increase his personal budget to EUR 46 million (Elayoubi 2013), despite Morocco having a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of a mere USD 2,892 in 2016 (according to the World Bank).

Policy Implications for Europe

The sections above show that the privatisation of state-owned institutions, land, and culture – which has been camouflaged as “modernisation” or “economic reform” – constitutes the central mechanism facilitating the consolidation of the politico-economic pact between the monarchy and the elite at the expense of large parts of the population in Morocco. However, this mechanism, which allowed the monarchy to weather the turbulent first months of the 2011 Arab uprisings, contains a number of contradictions which may not only affect the future of the country but also have important consequences for neighbouring Europe.

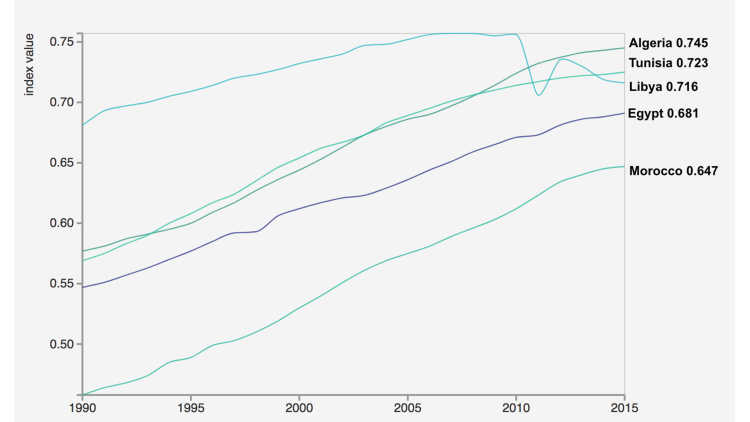

Although the neo-liberal turn occurred later in Morocco in comparison to other Arab countries, the transformation was much more extensive and costly at the social level (Catusse 2009). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ranked Morocco 123 (out of 188) in 2015, which was behind Iraq (121), Palestine (114), Egypt (111), and Tunisia (97).

In the last decade Morocco has also been regionally underperforming in the areas of female literacy rates, rural development, and health. According to one former pro-democracy activist, “Everything is difficult in the capital city, but things are catastrophic outside of Rabat” (interview with Y. Rguig, Rabat, 22 May 2017). External debt increased to 81 per cent of the country’s GDP in 2014 from an average of 50.4 per cent during the five years (2007–2012) preceding the Arab uprisings. This equates to every Moroccan paying approximately USD 500 annually to service the national debt (Aziki 2015), which is used in part to finance rent-distribution mechanisms (ibid). Against this background, it is no surprise that the first two countries affected by the 2011 Arab uprisings – namely, Tunisia and Egypt – were also the most diligent in implementing neo-liberal policies in the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century. In the case of Morocco, the alliance between the local elites and the monarchy means that a social revolution is still unlikely. However, increased inequality and an established culture of contempt towards the “losers” of the liberalisation and privatisation policies introduced in the last two decades mean that those dissatisfied with the regime will increasingly resort to one or more of the following three coping mechanisms: the informal economy, populism, or violent horizontal contestation.

The informal economy accounts for more than 14 per cent of Morocco’s GDP (CFCIM 2014) and allows millions of Moroccans to carve out a space for economic production partially free from state predation. However, large segments of the population are becoming increasingly involved in illegal activities, ranging from sex work to drug trafficking to money laundering. Morocco was traditionally an exporter of cannabis but is fast becoming a major transit hub for cocaine, heroin, and synthetic drugs from Latin America directed at the European market. Since 2013, for instance, drug seizures have increased in all categories (Médias24 2017), with more than 2.8 tonnes of cocaine seized in one year in Casablanca alone. Drug traffickers are using established export routes originating from regions long neglected by the state, such as northern Rif and the eastern border area in Oriental, to diversify their smuggling activities, be they new drugs or weapons or illegal migrants (Sidiguitebe 2014).

The growing popular dissatisfaction with the country’s representative institutions combined with the above-noted contempt towards the losers of economic reform is increasing polarisation between the haves and the have nots and leading to a political environment which threatens foreign investments. A case in point is a commercial boycott campaign launched online in May 2018 by a number of digital activists who singled-out three companies accused of setting prices out of reach for the majority of the population. Instead of seeing the boycott campaign as a warning sign from citizens upset at the growing economic inequality in the country, the representatives of the private companies targeted by the boycott and members of the government chose instead to snub boycotters, with one representative from Centrale Danone, one of the companies targeted by boycotters, calling the latter “traitors” and a government minister disdainfully referring to them as “dummies.” The distance between the regime and large parts of the population is also reflected in the irrational tone of some local conspiracy theories, which argue that the authorities’ relatively welcoming strategy vis-à-vis sub-Saharan migrants is a “ploy destined to recruit non-Moroccans in order to better repress the popular mobilisation to come” (anonymous, personal interview, January 2018).

In the last 10 years, the regime has also made heavy use of popular online news portals to delegitimise and defame all those who advocate for meaningful reform and threaten the supremacy of the palace. The popularity of local figures completely removed from formal institutions, such as Nasser Zefzafi, an undereducated former nightclub bouncer who was the leader of the 2017 Rif protests, illustrates the authorities’ success in delegitimising institutional alternatives. Should the country experience uprisings similar to those that occurred in neighbouring Tunisia or Egypt, a peaceful transition would be difficult given the absence of legitimate representative figures who are able to channel and address popular demands.

From a European perspective, it is therefore vital to recognise that the failure of the Moroccan reform model entails important risks of direct relevance to European security. Instead of lauding the cosmetic reforms of the Moroccan regime, the EU should pressure the monarchy to adopt reforms that genuinely strengthen the rule of law and human rights and facilitate inclusive economic growth.

Footnotes

References

Aziki, Omar (2015), CADTM – La Dette Publique Marocaine Est Insoutenable, CADTM – Comité Pour l’abolition Des Dettes Illégitimes, www.cadtm.org/La-dette-publique-marocaine-est (15 March 2018).

Benchenna, Abdelfettah, Driss Ksikes, and Dominique Marchetti (2017), The Media in Morocco: A Highly Political Economy, the Case of the Paper and on-Line Press since the Early 1990s, in: The Journal of North African Studies, 22, 3, 386–410.

Boukhars, Anouar (2011), Politics in Morocco: Executive Monarchy and Enlightened Authoritarianism, Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Politics, 23, London: Routledge.

Catusse, Myriam (2009), Maroc: Un État Social Fragile Dans La Réforme Néolibérale, in: Alternatives Sud, 16, 59–83.

CFCIM (2014), L’informel: Un poids inquiétant pour le Maroc, Le site d’information de la CFCIM, www.cfcim.org/magazine/21595 (23 March 2018).

Elayoubi, Salah (2013), Maroc. Mohamed VI, Le ‘Roi Des Pauvres’, Dépense sans Compter, in: Courrier International, www.courrierinternational.com/article/2013/11/19/mohamed-vi-le-roi-des-pauvres-depense-sans-compter (10 March 2018).

Guazzone, Laura, and Daniela Pioppi (eds.) (2009), The Arab State and Neo-Liberal Globalization: The Restructuring of State Power in the Middle East, Reading: Ithaca Press.

Maggi, Eva-Maria (2016), The Will of Change: European Neighborhood Policy, Domestic Actors and Institutional Change in Morocco, in: Politik und Gesellschaft des Nahen Ostens, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Oubenal, Mohamed, and Abdellatif Zeroual (2017), Les Transformations de La Structure Financière Du Capitalisme Marocain, in: Revue Marocaine Des Sciences Politiques et Sociales, XIV, April, 137–160.

Sidiguitiebe, Christophe (2014), Prolifération d’armes à La Frontière Entre Le Maroc et l’Algérie, in: Telquel.Ma, http://telquel.ma/2014/11/06/proliferation-armes-a-la-frontiere-entre-maroc-algerie_1421839 (15 March 2018).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

How to cite this article

Mekouar, Merouan (2018), Beyond the Model Reform Image: Morocco’s Politics of Elite Co-Optation, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-57967-0

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.