- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The Many Faces of Latin American Presidentialism

GIGA Focus Latin America

The Many Faces of Latin American Presidentialism

Number 1 | 2016 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Political developments in Latin America (LA) have repeatedly fuelled a rich, ongoing, and contentious academic debate about democracy and its deficits. LA is a region characterised by presidential democracies, a political system with arguably serious structural shortcomings. Brazil and Venezuela, both of which are currently undergoing severe political crises, are illustrative of both the perils of presidentialism and the institutional mechanisms that have enabled LA presidential democracies to survive, albeit with deficits.

Latin America is home to various political models of presidential democracy, including several variants of majoritarian presidentialism and presidential dominance as well as coalition presidentialism and other ad hoc solutions for minority governments.

Inter-institutional deadlocks due to presidents’ lack of adequate support in the respective Congress are perceived as a major shortcoming and a risk for presidential democracies.

“Coalition presidentialism,” as practiced in Brazil, has been an innovative LA solution for overcoming political deadlocks. However, the converse argument implies that without a coalition there might be no surviving president.

While the Brazilian Congress is trying to remove President Rousseff by means of impeachment, Venezuelan president Maduro is orchestrating a constitutional coup to disempower Congress. In both cases the presidents face an adverse majority in Congress, but the solution to the deadlock situation is different for each case.

Political stalemates between a congress and a president can be resolved by different means. On the one hand, presidents can try to sidestep and disempower the congress. On the other, minority presidents have sometimes been forced to resign, or removed by impeachment and other institutional equivalents to a “vote of non-confidence.”

Policy Implications

If presidents are unable to control their parties or coalitions, their removal may become a real possibility, despite fixed presidential terms. Some scholars call for constitutional reforms to allow for earlier elections. We argue that impeachment should be replaced by a vote of non-confidence (by a two-thirds majority). Then the political debate would be framed less in normative terms (questioning the moral integrity of the incumbent president) and more in political-programmatic and partisan-related terms.

Latin America as a Role Model in the Third Wave of Democratisation

In 1990 Juan Linz published an influential article in the Journal of Democracy entitled “The Perils of Presidentialism” in which he did not make many favourable prognoses for the recently established democratic, and presidential, regimes of the region. But the political developments of the following decades did not corroborate his sceptical view. In its latest edition of 2016, the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) classified 17 out of 19 Latin American political systems as democracies. Certainly, a few of them are regarded as consolidating democracies, while most classify as defective democracies. Since the beginning of 2016, LA has witnessed two major political crises, in Venezuela and Brazil, which despite being extreme are predictable crises within presidential regimes, as Linz and other classical authors argued in the early years of Latin America’s democratisation. In these two cases the presidents face an adverse majority in Congress: in Brazil, Congress is using the constitutional mechanism of impeachment to oust President Rousseff, while in Venezuela President Maduro is manipulating the rules of the decision-making process to disempower a confrontational Congress dominated by his political opponents. Both the crises’ constellations and the instruments being used to solve the impasse situations are not new in the region. The impeachment resembles previous presidential crises during the third wave in which presidents have had to leave power before finishing their constitutionally fixed mandates under the pressure of unfavourable majorities in congress and often also protests in the streets. Where the president has left power, though, democracy has persisted. The Venezuelan case, in contrast, more closely resembles the auto-golpe solutions (such as that in Peru in 1992), which saw congress unilaterally closed by the executive and the democratic regime break down. Latin American presidentialism is like a chameleon: it changes its colours in response to its political environment. But it is still the same political animal. While the institutional configuration may be prone to producing political stalemates, political actors are responsible for creating and resolving these stalemates. Moreover, they do not act in a socio-economic vacuum. In Brazil and Venezuela it was the economic downturns that fuelled the loss of support for the presidents among citizens.

The Latin American Debate about (Presidential) Democracy

Latin American political developments have repeatedly fuelled a rich, ongoing, and contentious academic debate about democracy and its deficits. The region’s scholarly literature has paid particular attention to the functioning of democratic institutions (with a special focus on presidentialism). The political and academic self-reflection on how these institutions can be improved has a long tradition. Since the 1970s Latin America has also contributed significantly to general theory building in comparative politics. The academic work of renowned scholars such as Guillermo O’Donnell has inspired the study of modern authoritarian regimes using the concept of bureaucratic authoritarianism. The region was also central in a large comparative project on the breakdown of democracies (coordinated by Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan, 1978). There can be no breakdown of democracy without democracy, which demonstrates that Latin America has a longer democratic tradition than other world regions. Latin America was also prominent in the literature on democratic transitions. Together with Portugal, Spain, and Greece, Latin American countries embarked on the third wave of democratisation in the 1970s. In fact, the work Transitions from Authoritarian Rule (edited by Guillermo O’Donnell, Philippe Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead), published in 1986, includes sections on Southern Europe and on Latin America. Juan Linz stimulated a broad intellectual debate about the virtues of parliamentarism and the perils of presidentialism (including models of semi-presidentialism). In Brazil in 1993 there was even a referendum on the form of government (presidential versus parliamentarian). Later, Guillermo O’Donnell critically analysed the “brown areas of democracy” and the deficits of accountability, introducing the concept of “delegative democracy.” Other LA scholars coined innovative analytical concepts such as “hyperpresidentialism” or “coalition presidentialism.” Today, these concepts belong to the academic mainstream and have enriched the analytical toolbox for the study of political institutions in developing countries beyond the region. More recently, the proponents of a “new constitutionalism” in Latin America have promised a more participatory and socially inclusive democracy.

Latin America’s broad and ongoing academic debate about democratic deficits is facilitated by the existence of a great number of independent universities, research institutes and think tanks. Institutions matter, and the self-reflection of the region’s scholars on how to improve their performance has a long tradition. In 2001, for instance, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) published a study entitled Democracies in Development, with the participation of many LA distinguished scholars, that analysed the effects of institutions on presidential democracies and assessed efforts to improve governance (a second revised edition was published in 2007). Another book published by the IDB in 2006, entitled Politics of Policies, consists of comparative analyses of institutions and political practices in Latin American presidential systems, with the objective of explaining why reforms endure in some countries and why some countries can easily change policies that are not working well. The cases of Brazil and Venezuela are currently being widely discussed within LA academia (and by LA specialists abroad), leading once more to the revision of former explanations, the introduction of new concepts, and proposals for institutional change. Perez-Linan’s contribution on the importance of building a congressional shield against impeachment and Marsteintredet’s arguments on the flexibilisation of the presidential term have recently been revisited, as there has been renewed interest in some of the classical texts on presidential democracy.

The Perils of Presidentialism

In his renowned article, Juan Linz began with the observation that most of the stable democracies of Europe and the Commonwealth at that time were parliamentary regimes, while presidential regimes were either authoritarian or unstable. He argued that the instability of presidential regimes was connected to its essential features – that is, the principle of dual legitimacy, according to which both the president and the legislature equally derive their power from the vote of the people, and the fixed mandates for both elected institutions. The fixed term introduced rigidities to the system that made crisis and conflict resolution more difficult, in contrast with the flexible solutions available to parliamentary regimes, including the dissolution of parliament, the vote of confidence, and the possibility of calling new elections. The direct election of the executive and legislative powers gave both president and congress direct, and dual, democratic legitimacy, thus inducing inter-institutional struggles and making it unclear which would prevail in the event of a conflict between the two. Linz further argued that the absence of majorities in congress, which increased the likelihood of deadlock, was a predictable consequence of these essential features of presidentialism.

However, Latin American presidential democracies survived since the third wave of transition initiated in the region in 1978, and the problems that Linz attributed to presidentialism turned out to be much less pervasive than previously thought. As early as the first part of the 1990s, academics pointed out that the potential risks that Linz had attributed to presidentialism actually concerned certain institutional constellations, especially the “difficult combination” of presidentialism with a multiparty system, where presidents might have difficulty gathering legislative support for their agendas. In such situations, whether presidents are able to overcome the shortage of legislative support or not is conditioned by institutional factors, such as the level of fragmentation of the party system or the constitutional authority of the executive, but it also depends heavily on their own strategic calculus. Presidents count on many constitutional powers to influence the legislative process (the so-called agenda-setting powers, including those to legislate unilaterally through decrees with the force of laws), but they use those powers differently. We have witnessed presidents who have resorted to them to govern alone, refraining from engaging in building majorities in congress and adopting imperial strategies that bypass the congress and the political parties sitting in it. And there have been presidents who have used unilateral resources in conjunction with a high degree of integration between the legislative and executive branches, mainly but not exclusively through the formation of cabinet coalitions.

Coalition Presidentialism and Presidential Breakdowns

In practice, Latin American presidentialism has been coping with its intrinsic perils by innovating both politically and institutionally. First, Latin America has shown that stable multiparty coalitions can be built in presidential regimes, even if the country has a weakly institutionalised party system. “Coalition presidentialism” has therefore been a specific strategic response to the systemic constraints. Under this scheme, the directly elected president serves as a coalitional formateur and uses his/her appointment prerogatives to recruit ministers from other parties in order to foster the emergence of a legislative cartel that could support her/his proposals in congress. Successful cases of coalition presidentialism have occurred across the Latin American political landscape, from Brazil to Chile to Uruguay, and a flourishing literature has shown that coalitions have not necessarily been short-lived and ad hoc under presidential rule but have, rather, resembled those in parliamentary democracies. In Brazil, it has become routine for presidents to preside over successive government coalitions within their mandates to adjust their support in Congress. Alongside the distribution of cabinet posts, presidents have also used other mechanisms to solve conflicts among coalition members and maintain control of the legislative process, such as their agenda-setting powers and pork-barrelling. The combination of all these features constitutes a model of government that departs significantly from the pure presidentialism found in the United States, which is unique and not representative of the whole group of presidential democracies.

This variant of Latin American presidentialism therefore demonstrates that coalitions are possible in presidential democracies, minority presidents are not necessarily weak, and a logic of confrontation does not always prevail in the inter-branch relations of presidential systems. However, coalition presidentialism presupposes a limited degree of political polarisation, which makes possible the cooperation between political parties across a broad ideological spectrum; a president who plays by the rules and recognises the limits of her/his status as a minority president; and a willingness to engage in power-sharing. Minority presidents may be tempted to use their wide emergency and agenda-setting powers to legislate alone, but this can get them into trouble. Insufficient party support in congress can become a problem for presidents, particularly those facing other challenges (such as a tough economic situation, scandals, popular discontent, and public mobilisation) and exhibiting weak leadership. Due to the electoral character of the office, the president is central to the political system, so a perceived failure to fix the country’s and the government’s problems directly affects presidential popularity, diminishing the propensity to cooperate of parties in congress and, in the case of government coalitions, of coalition partners.

Last year President Otto Perez Molina from Guatemala, who faced serious accusations of corruption, resigned as a result of pressure from Congress and street protests; this year President Dilma Rousseff is facing the threat of impeachment. The fact is that, despite the rigidity of mandates under presidentialism, since the 1980s many presidents have been challenged and 17 presidents have actually been forced to make an extraordinary exit from power before the end of the constitutionally fixed term. These presidential interruptions or presidential breakdowns have not led to a rupture of the democratic order, as the original argument on the perils of presidentialism claimed, despite most certainly being the outcome of very conflictive political situations. Thus, the inter-institutional conflicts have led to a premature change in the presidency, an arguably innovative institutional feature of presidentialism in Latin America. Very often, presidents have resigned while facing the pressure, but they have also been directly dismissed by congress. These congressional solutions often bear a resemblance to the flexible solutions that parliamentary regimes implement to cope with crisis (namely, early elections, votes of no confidence, and congressional elections of the presidential successor). Even impeachment, which requires a special two-thirds majority in the two chambers and is the exceptional conflict-resolution mechanism available in presidential constitutions, can resemble a vote of no confidence, as in the case of President Fernando Lugo’s ousting from power in Paraguay.

On the bright side of the equation, the political and institutional innovations of Latin American presidentialism have provided mechanisms for dealing with inter-institutional conflicts and have avoided, with different intensities according to the case, the risks of democratic breakdown. On the shady side, the building and maintenance of congressional coalitions has proved to be demanding for presidents as well as for the political regime, and has not been exempt from clientelist and corrupt practices. The “fluid” use of certain constitutional mechanisms to dismiss the president has also proved disruptive in contexts of political polarisation.

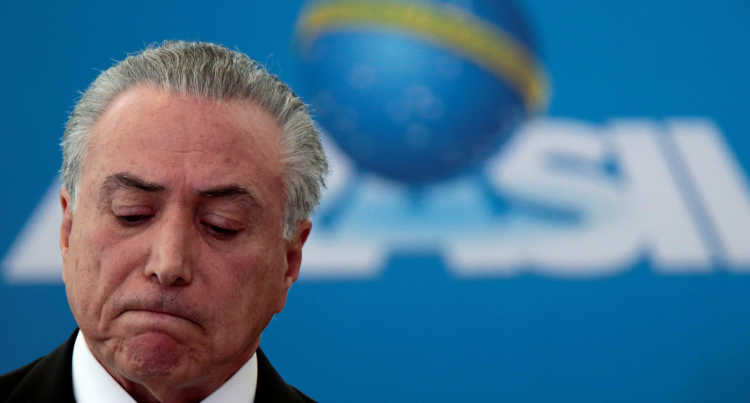

Coalition Presidentialism in Crisis: President Dilma Faces Impeachment

After more than 40 hours of speeches, late in the evening of Sunday, 17 April, Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies voted on the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, with 367 of the 513 deputies backing the move. This was a comfortable majority beyond the two-thirds majority of 342 needed to advance the case to the upper house. Outside Congress, pro-impeachment protesters, dressed in green and yellow and draped in the national flag, celebrated. A fence separated them from the Dilma defenders, clothed in red. The deputies had 30 seconds each to justify their vote. Pro-Dilma voters invariably referred to the impeachment as an unjustified golpe against the president. Pro-impeachment deputies voted based on an eclectic bunch of reasons far beyond the actual violation of the norm that caused the impeachment move – that is, the president’s manipulation of accounts, last year, to make the fiscal deficit look smaller than it actually was.

The high number of votes in favour of the impeachment are not easy to understand without acknowledging the context. President Rousseff is suffering from extremely low popularity as a result of economic and political factors: the country is facing a serious recession, while inflation and the unemployment rate are both at approximately 10 per cent. The exposure of the Petrobras corruption affair, which involves the president’s Workers’ Party (PT), as well as its coalition partners and many others, has infuriated the public and motivated protests. Even though there is still no evidence that Rousseff was directly involved, many people believe she must have known what was going on. Due to these events, latent rivalries among coalition members have become apparent. As a matter of fact, the impeachment moved forward when relations between the PT and the PMDB, the major coalition partner that controls the vice presidency and the presidency of the two congressional chambers, fell apart. As Sergio Abranches, who once coined the concept of “coalition presidentialism,” has put it, the impeachment is not a judicial process, but a political process within the procedural framework established by the constitution. While the interpretation of the actual causes of an impeachment will always invite legal controversy, the gist of the matter is that a president without a partisan shield in congress has little chance of surviving an impeachment. We have seen legislatures failing to impeach the guilty, and presidents against whom no evidence could be identified being ousted.

All Brazilian presidents since the transition have been exposed to the threat of impeachment, but only one attempt, 24 years ago, has succeeded – against Fernando Collor de Melo, the first popularly elected president in Brazil after 21 years of military rule. Collor’s attempt to implement a radical economic agenda to combat inflation resulted in recession, unemployment, and popular dissatisfaction. He was a president without the backing of a significant party of his own, who governed with an imperial and confrontational style, and with little congressional support from other parties. Dilma Rousseff has the backing of her party (which is an important but nevertheless minority party within a highly fragmented Congress), but she no longer has a coalition behind her. The Brazilian Senate is currently in charge of assessing the merits of her impeachment. Her chances of survival are slim, if any.

The Autocratic Face of Presidential Democracy: Back to the 1990s?

While coalition presidentialism renovated Latin American presidential democracy, giving it a consensual twist, there is also an autocratic tradition within the region that has never become extinct. By chance, the daughter of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori is currently one of the contenders in the run-off ballot to become the next president of Peru. Fujimori (together with Carlos Menem and Fernando Collor de Melo) provided inspiration for Guillermo O’Donnell’s famous delegative democracy argument of the early 1990s. Delegative democracies empower an individual to be the embodiment and interpreter of the highest interests of the nation for a specific amount of time, in isolation from political institutions and organised interests. In these regimes, the weighty legacy of past authoritarian tendencies combined with a context of deep social and economic crisis results in the exalted status of the presidency and weak and heavily manipulated legislative and judicial branches. Carlos Nino’s “hyperpresidentialism” is another term coined during those years. It emphasises the superiority of the executive, which is enshrined in the constitution, and the excessive use of unilateral mechanisms in the adoption of decisions. All three presidents were similar in this regard, but it was Fujimori who mounted an auto-golpe in response to congressional resistance to approving his neo-liberal plan of reforms. Through a decree he dissolved Congress, gave the executive all legislative powers, and suspended much of the constitution. New elections were called and a new constitution enacted, according to which Congress became unicameral and largely dominated by Fujimori’s supporters.

Unlike Fujimori, President Menem enjoyed the support of his party, Peronism, which held favourable majorities in the two chambers of Congress over two presidential terms. Menem demonstrated that he was a high-risk politician, ready to act on the margins of the constitution by using decretismo or packing the Supreme Court. But his parallel ability to work with his party and his party’s allies at the congressional level was key to the success of an ambitious policy programme and the persistence of his leadership over a prolonged period of time.

Presidents prone to unilateral excursions enjoying strong political backing have populated the regional landscape – for instance, as part of the pink tide during the first decade of this century. Hugo Chávez, Rafael Correa, and Evo Morales have also exemplified a delegative and hyperpresidential style of government, notwithstanding their participatory discourses. Their constitutions, embraced in the wave of ”new constitutionalism,” are very much in line with old school Latin American presidentialism in this regard. Latin American political institutions and constitutions are not at all static, but some elements have proved to be more resilient than others. Since the beginning of the current democratic period in 1978, 16 new constitutions have been promulgated (mostly in the 1980s and 1990s). Moreover, a total of 275 constitutional amendments were made between 2000 and 2015, a period during which only three new constitutions came into force. While LA constitutions have become more inclusive and have embraced more social and participatory rights, some authors, such as Roberto Gargarella, argue that the “engine room of the constitution” has not changed much. The engine room consists of the power-granting provisions of the constitution that determine the relative authority of political institutions and actors. It is interesting that although presidential agenda-setting power has very often been increased, in many cases the power of congress and the judiciary has been expanded as well. The effects of these contradictory reforms depend to a great extent on the political majorities. A president with a large majority can use his/her power to neutralise congress and the judiciary. A minority president may become beleaguered by an oppositional majority. This is a real possibility because through electoral reforms Latin American party systems have become more inclusive, and fragmented. Moreover, the now constitutionally empowered judiciary is another actor with potential veto power.

Venezuela: The Authoritarian Face of Presidentialism

After the government of Venezuelan president Maduro was defeated in the legislative elections in December 2015, the governmental majority in the outgoing Congress enhanced the partisan control of the Supreme Court and appointed 13 new judges by blatantly violating the constitution. The Supreme Court has since proved to be a tremendous functional instrument for serving the executive and disempowering the opposing Congress. First, the court called into question the status of three congressional representatives who would have given the opposition a two-thirds majority in Congress (the necessary majority to pass constitutional amendments or to convene a constitutional assembly). Second, it reinterpreted the constitution to limit Congress’s oversight and control powers, and it invalidated legislation (such as an amnesty law for convicts seen as political prisoners by the opposition) with political-ideological arguments. Third, it corroborated the president’s power to legislate by decree, notwithstanding Congress’s refusal to prolong the delegation of powers to the president.

We interpret this behaviour as a constitutional coup engineered by the president in cooperation with the Supreme Court. Javier Corrales coined the concept of “autocratic legalism”, a ruling strategy that has a long tradition in Latin America. The dictum “for my friends, everything; for my enemies, the law” has been attributed to former Brazilian president Getulio Vargas. The tendency to use the law in a partisan and biased way against political adversaries has always remained alive. Recently, the tendency of politically submissive supreme courts to modify or reinterpret the constitution has re-emerged in Nicaragua and Honduras, where the Supreme Court in each case has invalidated constitutional stone clauses that prohibited presidential re-election. In both cases the court rulings favoured the incumbent presidents. The case of Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua exemplifies the traditions of personalism and caudillismo. He first became a revolutionary leader to topple a personalistic authoritarian dictatorship, then evolved from an autocratic revolutionary to an actor playing by the rules of the democratic game, only to end up as a personalistic ruler in a democracy with strong authoritarian traits.

With regard to Venezuela, Maduro did not really change the political logic of the Bolivarian regime. During the presidency of Hugo Chávez and at the beginning of the Maduro presidency, the government party controlled the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. Therefore, there were no conflicts between the different state powers. While autocratic tendencies were evident during the Chávez presidency, they could still be interpreted as being within the domain of a “delegative democracy” with a strong plebiscitary component. Maduro then crossed the line in the direction of authoritarianism. This explains why, for the moment, he is prevailing in the conflict and standoff with Congress. Under democratic conditions, Congress is generally the institution that holds the strongest position in the event of conflict.

It’s the Economy, Stupid

As Bill Clinton’s campaign slogan against incumbent George Bush during a period of economic recession proclaimed, it is the economy that explains – at least in part – why two incumbent Latin American presidents are in trouble. Political crises do not evolve in a socio-economic vacuum. In Brazil and Venezuela the economic downturn has fuelled the presidents’ loss of support among the citizens. Although the governing PT in Brazil is deeply enmeshed in the corruption morass, the same is true for some of the principal adversaries of President Rousseff in the PMDB, until recently the main partner of her coalition. But it is in the context of an economic slump and social polarisation about distributional issues that a coalition to impeach the president has been cemented. However, while the impeachment may bring about a temporary solution to the political stalemate, the IMF forecast of negative growth of -3.8 per cent in Brazil for the current year and zero growth for next year means there is no easy way out of either the political or the economic crisis. Moreover, politics is now much more polarised and adversarial than during the past 20 years. In Venezuela, the economic crisis is even worse, with the economy shrinking by 8 per cent and an inflation rate of up to 500 per cent. By ignoring the verdict of the electorate in December and by subsequently disempowering Congress, the government has clearly crossed the line between a defective democracy and an authoritarian regime. It is quite difficult to predict how the political stalemate, the partisan polarisation, and the economic crisis in Venezuela can be overcome. Perhaps this will necessitate external pressure and support. In the context of Latin America’s economic slowdown, it appears that the period of fine-weather democracy may be coming to an end and that some of the “perils” and less pleasant traits of presidential democracy may resurge.

For a More Sincere Solution to Gridlock

Presidentialism is here to stay. The probability of a blanket change to parliamentary democracy is close to zero; worldwide, the preferred type of democracy, (whether presidential or parliamentary), is quite entrenched. Therefore, the structural challenges of presidential democracy will also not disappear. There is always the risk of political gridlock when the president has no majority in parliament. Two extreme solutions have frequently emerged in Latin America when a political stalemate has emerged: either the president has prevailed, by bypassing or even dissolving congress, or the congress has carried the day by unseating the president. Both ways out of crisis result in a short-term solution to the stalemate, but in both cases there is a risk of future costs for democracy. We believe that the risks are higher in the first case, because a presidential triumph may lead to an authoritarian variant, the unlimited concentration of power in the hands of the head of the executive. Meanwhile, a triumph on the part of the congressional majority may increase political polarisation, because the presidential party will invariably argue that congress is defrauding those who voted for the president or, in other words, is reversing the result of the presidential elections.

In part, political polarisation is connected to the fact that impeachment concerns the president’s violation of norms or his/her misconduct in office. In reality, though, it is the size of the presidential majority that determines his/her fate. This was clearly the case in Paraguay against President Lugo, and it is now the case in Brazil with President Rousseff, where the causes of the impeachment have generated enormous controversy. It would probably be more honest if LA constitutions substituted impeachments with votes of non-confidence with special majorities. The political debate would then be framed less in normative terms (questioning the moral integrity of the incumbent president) and more in political-programmatic and power-related terms, which often constitute the background to impeachments. Admitting such a semi-presidential solution into the constitution would better reflect what is going on in practice. But if a presidential regime is tilting towards authoritarianism (as in Venezuela), the institutional design loses significance as such. In such a case, the international community should consider undertaking action.

The intrinsic risks of presidentialism as well as the Latin American political and institutional innovations to cope with them are relevant for policymakers and scholars beyond this region. After all, presidential and semi-presidential regimes have extended to all other world regions with the third wave of democratisation. When democracy becomes the only game in town, situations of gridlock are very likely in presidential regimes. The extreme solutions a la latina have proved to be costly but still better than the return to authoritarian rule that was frequently the case in the past.

Footnotes

References

Abranches, Sergio (2016), O consenso impossível e o agravamento da crise no presidencialismo de coalizão, in: ecopolitica, 18 April (2 May 2016).

Bertelsmann Stiftung (ed.) (2016), Transformation Index BTI 2016, Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Corrales, Javier (2015), Autocratic Legalism in Venezuela, in: Journal of Democracy, 26, 2, 37–51.

Gargarella, Roberto (2013), Latin American Constitutionalism, 1810–2010: The Engine Room of the Constitution, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) (2006), The Politics of Policies: Economic and Social Progress in Latin America, New York, NY: IDB.

Linz, Juan J. (1990), The Perils of Presidentialism, in: Journal of Democracy, 1, 1, 51–69.

Linz, Juan, and Alfred Stepan (eds) (1978), The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Marsteintredet, Leiv, and Einar Berntzen (2008), Reducing the Perils of Presidentialism in Latin America through Presidential Interruptions, in: Comparative Politics, October, 41, 83–101.

Nino, Carlos (1996), Hyperpresidentialism and Constitutional Reform in Argentina, in: Arend Lijphart and Carlos H. Waisman (eds), Institutional Design in New Democracies: Eastern Europe and Latin America, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

O’Donnell, Guillermo (1973), Modernization and Bureaucratic-Authoritarianism: Studies in South American Politics, Berkeley, CA: University of California, Institute of International Studies.

O’Donnell, Guillermo (1994), Delegative Democracy, in: Journal of Democracy, 5, 1, 55–69.

O’Donnell, Guillermo (2004), Why the Rule of Law Matters, in: Journal of Democracy, 15, 4, 32–46.

O’Donnell, Guillermo, Philippe C. Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead (eds) (1986), Transitions from Authoritarian Rule, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Payne, J. Mark, et al. (2001), Democracies in Development: Politics and Reform in Latin America, New York, NY: IDB.

Perez-Linan, Anibal (2007), Presidential Impeachment and the New Political Instability in Latin America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Llanos, Mariana, and Detlef Nolte (2016), The Many Faces of Latin American Presidentialism, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-46909-7

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.