- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Ageing, Temporary Migrants: Life beyond Retirement in Dubai

GIGA Focus Middle East

Ageing, Temporary Migrants: Life beyond Retirement in Dubai

Number 6 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3611

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), while exhibiting one of the highest shares of migrant workers in its national work force globally, has very restrictive immigration policies. As a standard procedure, work visas for migrants are curtailed after the age of 65. The UAE is therefore a key site for understanding transnational inequalities premised on citizenship and social security in the Global South.

The influx of labour migration to the UAE having begun in earnest only in the 1970s, the ageing of its migrant population is critically advancing. Today, these migrants’ children, who were born in the UAE, are engaged in the workforce there. Tax-free salaries, or “end-of-service benefits” offered to migrants in the UAE, however, are not adequate to provide a decent life after retirement for most.

This is particularly challenging for those who lack the necessary resources to keep their older family members in the host countries, and for those who originate from socio-economically and politically unstable countries, where the question of “return” after retirement is much less feasible.

Prolonging residency after retirement is possible; in fact, most migrants desire it, as they want to be surrounded by their children, grandchildren, and community into old age. Although in recent years the UAE has introduced longer-term visas, including for retired people, these schemes typically target high-net-worth individuals. Yet even with adequate resources, older migrants still face uncertainty, as keeping up their residency and financial subsistence requires continual renewals and investments, respectively.

Policy Implications

Gulf policymakers should make retirement-savings schemes mandatory for its temporary migrants. This will not only financially enable some of them to envision a future in the Gulf beyond retirement but also benefit the Gulf states, which aim to attract consumers and investors. Furthermore, more origin countries should offer social protections, such as pension rights, for their ageing overseas workers in the Gulf.

Retirement as a Source of Ambivalence for “Permanently Temporary” Migrants

A significant number of migrants to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) spend most of their adult lives working there on renewable temporary work contracts. Migrants who are eligible for family unification establish multigenerational existences there, where they are surrounded by their children and grandchildren. Yet reaching the age of 65 engenders ambivalent feelings about the future. That ambivalence is integrally related to a lack of citizenship and social security for migrants in the UAE. These structural constraints bring forth questions about residential arrangements and economic subsistence for retired migrants. From an emotional point of view, retirement also reveals concerns about family unity in the UAE. While retired migrants can prolong residencies in the UAE, for families who do not have substantial resources or the necessary networks to remain, returning to their countries of origin appears the only viable option.

We know very little about the experiences of older migrants in the UAE and other Gulf states. This lacuna is significant considering the fact that the Gulf states employ the highest proportion of migrant workers in the world, and migrants over the age of 65 constitute a significant percentage of these rapidly ageing populations (Fargues 2011: 297). Their experiences require close attention because the Gulf states, with their restrictive immigration policies, are key sites for understanding global inequalities premised on citizenship and social security, which have direct implications on the well-being of ageing migrant populations. Although in recent years the UAE has introduced longer-term visas, including for retired people, these schemes typically target high-net-worth individuals. Thus, despite being regarded as signs of a more inclusive migration regime, these visas will likely reinforce inequalities by excluding the majority of migrants, who remain ineligible for these schemes.

The author’s research in Dubai between 2015 and 2016 with first-generation migrants’ adult children, who were born and raised in the UAE, unexpectedly sheds light on the experiences of their parents, who had reached or were nearing retirement age. During the interviews, questions regarding the future plans of UAE-born migrants prompted them to reflect on retirement as a source of uncertainty for their families in the UAE, and on how to make sense of this particular stage in their parents’ lives. Their parents arrived in the UAE as early as the 1960s and as late as 1985, from countries including Somalia, India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, Iran, and Syria, and spent the majority of their adult and working lives in the UAE. At the time of the interviews the parents of participants were aged between 60 and 73. Their professions varied, including business owners, accountants, doctors, engineers, teachers, clerks, and technicians, as well as mid- to high-level managers. Out of 30 participants, the parents of five had returned to their country of origin upon retirement, the parents of ten others continued to work beyond the age of 60, and the rest lived in the UAE on renewable temporary visas. For those originating from Syria, Somalia, and Iraq, return upon retirement, if migrants had even previously envisioned this, had become untenable due to the political situations in these three origin countries.

Most of the participants revealed that even though remaining in Dubai upon retirement is a costly option, most migrants prefer it in order to be near to their families, friends, and social networks, who typically remain in the UAE. Residing in Dubai or maintaining a transnational family life without a pension requires both socio-economic resources and reliance on family and social networks. Therefore, in this context it is privilege in the face of the UAE’s restrictive immigration policies that determines mobility upon retirement for migrants. What is unique in the case of the UAE, however, is the vast importance of family and social networks, which can often circumvent migrants’ need for economic capital to prolong their residency upon retirement. The author’s research findings demonstrate how the kafala (sponsorship) system, which encourages mobility upon retirement, also allows a degree of flexibility for some migrants to remain in the UAE after this point. This is thanks to the hands-off approach to migration management in the UAE, where the responsibility for issuing visas is given to companies and to individual employers and managers, whether these are UAE citizens or not. Subject to the approval of the authorities, employment visas could be issued annually after the age of 65

The case of migrants reaching retirement age in Dubai shed light upon the diversity of experiences of ageing migrants on a global level. There is a disproportionate focus on the experiences of ageing labour migrants in Western Europe and North America. These groups, albeit with legal restrictions, have options to remain in the host countries or move back and forth in order to maintain ties with their children in the host societies. While experiences of ageing migrants in temporary migration settings are receiving increasing attention, most of the research is outside the Gulf states and focuses on low-wage migrants who often have no right to family unification in their host countries. The financial and emotional frictions arising from a “permanently temporary” status among retired migrants in the UAE therefore expands the understanding of the role national residency regimes play in enabling, imposing, or restricting the mobilities of older migrants, and shaping the quality of their lives and well-being.

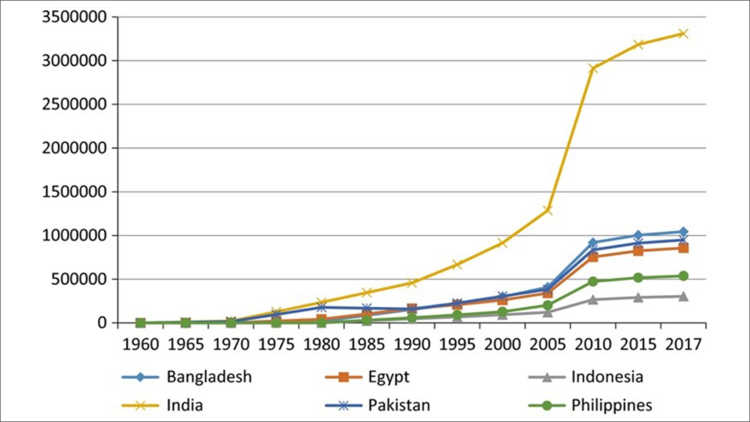

Migration Governance in the UAE

The Gulf has witnessed an influx of migration since the oil boom in the 1970s, to such an extent that today migrants make up nearly 90 per cent of the country’s population in countries such as the UAE. Migrant workers also constitute 99 per cent of the private workforce in the UAE. Figure 1 depicts available numbers on migration to the UAE from the top sending countries between 1960 and 2017. Regardless of their years of residence, migrants have no formal route to permanent residency or citizenship, or to social security. They are regulated through a temporary, sponsored visa programme known as kafala, and are granted two- to three-year renewable residency permits linked to employment. While low-wage migrants are typically more transient in the UAE, those eligible for family unification have made the UAE their unofficial home, residing “permanently temporarily” across decades and generations.

The age of 65 marks the start of the retirement period for migrants. Since residence is typically tied to work visas in the UAE, for most migrants this means a curtailment of work/residence permits in the UAE. Healthcare benefits, provided to migrants by their employers, are also discontinued at this stage. Yet, migrants constitute 27 per cent of people aged over 65 in the Gulf (Fargues 2011: 297). This shows that even after the age of retirement, many migrants continue to reside in the UAE. If retired migrants wish to remain in the UAE, one option is to be sponsored by their children with valid residency visas. For this, children must have at least a two-bedroom flat and a monthly minimum salary of AED 20,000 (approximately USD 5,000), along with proof that they are the sole provider for their parents and there is no one to take care of them in their home country (U.AE 2021). Subject to the approval of the authorities, employment visas could also be issued after the age of 65. Yet as the author's research indicates working beyond the age of 65 is not perceived as ideal for most migrants.

Purchasing real estate or setting up businesses in the UAE also accords migrants renewable visas. Yet the financial investment required for these visas renders this option inaccessible for many. Although in recent years the UAE has introduced longer-term visas, and even pathways to citizenship, these typically target highly talented individuals or high-net-worth individuals, and only on an ad-hoc basis. For example, retirement visas introduced in 2020 offer five-year renewable visas for people with a monthly income of AED 20,000 who own property in Dubai worth at least AED 2 million (approximately USD 550,000) (U.AE 2021). Since the majority of migrants remain ineligible for these new visas, experiences of ageing in this context are likely to become even more unequal, not only between citizens and migrants, but also between migrants with different socio-economic resources and citizenships, the latter reflecting the different political and socio-economic conditions in origin countries.

The tax-free salaries offered to migrants are often seen as a trade-off for a lack of citizenship and social security in the UAE. Yet the shortcoming of this proposition is illustrated by the fact that nearly half of migrants in the UAE state they have “no plans to ensure an adequate standard of living after retirement” or that they “plan to work beyond the retirement age” (see Castelier 2021). Some companies may provide pension plans, but most migrants in the UAE do not have public pensions and are instead offered “end-of-service benefits” ( Castelier 2021). Migrants may contribute to the pension systems in their home countries, so long as there are provisions for overseas workers.

Migrant workers’ ability to accumulate savings in the UAE in preparation for retirement is also very much related to workplace hierarchies based on race and nationality. For instance, despite holding similar qualifications, “white expats” tend to receive better salaries and employment packages, including incentives such as transportation, housing, and education allowances for children. The employment packages of most middle-class South Asians and Middle Eastern workers do not include such privileges, as companies take advantage of these employees being “better off” in Dubai than they would be back home in terms of salaries and lifestyle (Vora 2013: 76–77). Even though family and social networks can provide retired migrants with temporary visas in the UAE, those with little or no savings are less likely to be able to maintain a decent lifestyle if they remain in the UAE, or are more likely to depend on their families for financial support, as this research shows.

Ability and Desire to Remain in Host Countries after Retirement

In most restrictive immigration regimes, such as many in Asia and the Gulf states, mobility upon retirement is enforced, as work visas are not issued after this, and returns to origin countries are typically compulsory, especially for lower-wage migrants (see Amrith 2021). Yet not all migrants experience “being temporary” on the same terms and under the same conditions. Depending on gender, skills, age, class, and race, as well as on citizenship status, some migrants have greater flexibility to negotiate the temporary migration regimes that may restrict or impose migrants’ length of stay in host countries. For example, middle-class and wealthy migrants from the Global South in the Gulf states can manage to mitigate the effects of being temporary by maintaining a set of global connections, such as investing in alternative passports (see Surak 2020). For some of these groups, lack of citizenship rights in the Gulf is irrelevant due to their privileged socio-economic statuses or passports, which shield them against the vulnerabilities of having liminal legal statuses in these host countries (see Kanna 2011: 36; Vora 2013; Gardner 2010). By contrast, the mobilities of lower-wage migrants are firmly policed, and migrants from politically volatile countries often feel constrained in their mobility, with few or no options to move elsewhere, so stay put in the Gulf, at times involuntarily (see Babar, Ewers, and Khattab 2019).

While remaining in one place, in other words being immobile, is often understood in the wider literature on the Gulf to be the result of constraints and is attributed to disempowered and poor individuals (Glick Schiller and Salazar 2013: 4), the author’s research shows that immobility is an active strategy to negotiate restrictive immigration regimes that enforce mobility for older migrants, and to keep families together upon retirement. Thus, drawing on Schewel (2019), in this research “retirement immobility” is understood as “continuity in an individual’s place of residence over a period of time.” While the ability to remain depends on migrants’ residency rights, access to healthcare and pensions and long years of residence in the host country inevitably result in migrants having stronger attachments and emotional bonds to these places, leading to a preference to remain (see Ali 2011; Akıncı 2020, on second-generation non-nationals in Dubai; Walsh 2018 for older British migrants in Dubai). Moreover, for some migrants, going “home” may not be viable due to the political circumstances there, and immobility may be their only option.

Since remaining in the UAE after retirement without permanent residency and social security requires resources, immobility is a valuable asset typically accessible to privileged migrants. Arguably, immobility is also achieved through privatisation of migrant governance through citizen/migrant sponsors, which allows some flexibility for older migrants to remain in the UAE. Yet even with adequate resources, older migrants still face uncertainty, as keeping up their residency and financial subsistence requires continual renewals and investments, respectively. The lack of citizenship and permanent settlement options for older migrants continues to be the most significant source of uncertainty in retirement, especially for those who lack the necessary resources to keep their families in the host countries, and for those who originate from socio-economically and politically unstable countries, where the question of “return” is much less feasible.

Capturing Complexities of Ageing in the Global South

The UAE and most of the Gulf states, whilst located in the Southern Hemisphere, are some of the richest countries in the world. UAE passports are also one of the strongest globally, according to the Global Passport Index. Thus the exclusion of labour migrants in the Gulf from social security provisions, most of whom originate from countries in the Global South and who spent their lives working in these places, generate new, even more pronounced inequalities within regions that are categorised as part of the Global South. The Gulf, their influx of immigration having begun only in the 1970s, is a region where the ageing of the migrant population is not yet advanced. Migrants who moved to the region in the late 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s, predominantly from countries in the Global South, are now approaching the age of retirement and are confronted by difficult questions regarding their lives after this stage. Considering their integral role in the functioning of Gulf economies, Gulf policymakers should make retirement-savings schemes mandatory for its migrant labour force, with both employers and employees contributing to it. National legislation should support employers in their contribution towards their employees’ social security coverage, so that more equal treatment between the national and non-national workforce can be achieved. This will financially enable more migrants to envision a future in the Gulf beyond retirement. Immigration policy should also consider making concessions for migrants who spent a substantial amount of time in these countries before retiring. For instance, most migrants in the UAE are unable to meet the financial requirements for retirement visas, making the option to retire in the UAE possible only for high-net-worth individuals. As the UAE economy increasingly looks to attract consumers and investors to settle there, securing visas and social security for migrants would expand the number of non-nationals who could potentially consider making the UAE a longer-term home and investing their life savings there.

Furthermore, more origin countries should offer social protections, such as pension rights, for their ageing, overseas workers in the Gulf, who are not included in their host countries’ national pension schemes. This is particularly important for the most vulnerable workers who are in low- to medium-earning jobs and unable to amass substantial savings to contribute towards their old-age pensions. Currently, a number of sending countries (such as India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Jordan) offer voluntary schemes for its nationals working in these countries. This should be a more common practice for labour-sending countries to the Gulf states, and concessions should be offered to low-wage workers for voluntary insurance schemes.

An extended contribution on the topics covered by this GIGA Focus is forthcoming as part of a special issue of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies entitled “Southern Re-Configurations of the Ageing–Migration Nexus”.

Footnotes

References

Akıncı, İdil (2020), Culture in the “Politics of Identity”: Conceptions of National Identity and Citizenship among Second-Generation Non-Gulf Arab Migrants in Dubai, in: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46, 11, 2309–2325.

Ali, Syed (2011), Going and Coming and Going Again: Second-Generation Migrants in Dubai, in: Mobilities, 6, 4, 553–568.

Amrith, Megha (2021), Ageing Bodies, Precarious Futures: The (Im)Mobilities of “Temporary” Migrant Domestic Workers Over Time, in: Mobilities, 16, 2, 249–261.

Babar, Zahra, Michael Ewers, and Nabil Khattab (2019), Im/Mobile Highly Skilled Migrants in Qatar, in: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45, 9, 1553–1570.

Castelier, Sebastian (2021), Work in Gulf Means Short-Term Gains, Transient Lifestyle, 26 May, Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East, www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/05/work-gulf-means-short-term-gains-transient-lifestyle (1 December 2021).

Fargues, Philippe (2011), Immigration without Inclusion: Non-Nationals in Nation-Building in the Gulf States, in: Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 20, 3–4, 273–292.

Gardner, Andrew M. (2010), City of Strangers, Ithaca: ILR Press.

Glick Schiller, Nina, and Noel B. Salazar (2013), Regimes of Mobility Across the Globe, in: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, 2, 183–200.

Kanna, Ahmed (2011), Dubai, the City as Corporation, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schewel, Kerilyn (2019), Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies, in: International Migration Review, 54, 2, 328–355.

Surak, Kristin (2020), Millionaire Mobility and the Sale of Citizenship, in: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47, 1, 166–189.

U.AE (2021), Residence Visa, https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/visa-and-emirates-id/residence-visa (4 November 2021).

Valenta, Marko et al. (2020), Temporary Labour–Migration System and Long–term Residence Strategies in the United Arab Emirates, in: International Migration, 58, 1, 182–197, https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12551.

Vora, Neha (2013), Impossible Citizens, Durham: Duke University Press.

Walsh, Katie (2018), Returning at Retirement: British Migrants Coming “Home” in Later Life, in: British Migration: Privilege, Diversity and Vulnerability, Oxon: Routledge, 182–198.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

How to cite this article

İdil Akıncı (2021), Ageing, Temporary Migrants: Life beyond Retirement in Dubai, GIGA Focus Middle East, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-76250-2

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.