- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The Gülenists in Exile: Reviving the Movement as a Diaspora

GIGA Focus Middle East

The Gülenists in Exile: Reviving the Movement as a Diaspora

Number 3 | 2019 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Facing a heavy-handed crackdown since the 15 July 2016 abortive coup, many Gülenists are fleeing Turkey and seeking refuge mostly in European countries. With this ongoing influx, a Gülenist diaspora is in the making. The fall from grace and the traumatic experience of exile have paved the way for heated internal debates on what went wrong and how the movement may start over.

Although the Gülen movement has heavily invested in the Global South, most followers have sought refuge in Western democratic countries, where the rule of law may protect them better from the Turkish state’s aggression. Since 2016, the number of asylum seekers from Turkey has increased five-fold in the European Union; many of them belong to this movement.

The contradictions of the Gülenist organisation illustrate the common pitfall of jamaahs (“religious communities”) in Turkey, which first emerged in the mid-1920s but could not fully translate themselves into the new political and social order. The movement’s destiny as a diaspora, however, largely depends on this legacy.

Strikingly, the Gülenists in exile live in a comfort zone, diminishing the odds of reform happening: the movement’s victim status enables it to swim with the tide of anti-Erdoğan sentiment in the West, while its modern, non-violent, eager-to-integrate stance – standing in contrast to many other Islamic movements – appeals to Western policymakers.

But, for the first time ever, criticism from within the movement has been loudly heard, and reverberated across its membership base. Exile has triggered an emotional break among many Gülenists, who are now revisiting their very conceptions of state, nation, and religion.

Policy Implications

The Gülen movement is at a crossroads of its own making. German and European policymakers have the unique opportunity to shape the future trajectories of this movement, and should push for full organisational transparency. From a broader perspective, they can establish channels – such as dialogue conferences – between isolated groups in exile, and thus contribute to preparing for the emergence of a new social contract in Turkey.

The Gülenists Cast Out

“We still do not know what is really inside the [Gülen] Movement [GM],” Şerif Mardin, the leading scholar on the sociology of religion in Turkey, avowed in 2011 (Düzel 2011). From its humble beginnings in the 1970s, the Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen has managed to turn his mosque congregation into one of the largest Islamic networks in the world. His movement has expanded across the globe through education and interfaith dialogue, with a supporter group estimated at between 500,000 and two million strong in Turkey as well as having some 2,000 schools in about 160 countries by the early 2010s. Compared to its vast presence, however, substantial knowledge about the movement was only limited under its incongruent depictions – varying from a faith-based humanitarian civic movement to a criminal gang engulfing the Turkish state apparatus (Watmough and Öztürk 2018). The past few years have changed a lot in Turkey. That also includes the status of the GM, which is today more exposed than ever to public scrutiny.

Whereas the GM used to win the hearts and minds of many Turks through the success of its wide-reaching education network both at home and abroad, Gülen-hatred – like the Kurdish question – is one of the few elements uniting a polarised Turkey today. For many observers, the GM’s bureaucratic and media force has been an enabler for the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) in its zealous power grab over the last decade. In their eyes, it has also functioned as an anti-democratic force helping to jail anti-Gülenist journalists, fabricating evidence against the military in two mass trials, while also sabotaging the government’s peace process with the Kurds (Zaman 2019). Once the secular establishment had been neutralised by 2010, the affinity between the AKP and the GM was replaced by a massive war of attrition that reached its apex in the 15 July 2016 abortive coup – for which current president Tayyip Erdoğan blamed Gülen and his followers.

Ostensibly only seeking to neutralise this subversive plot, the Turkish state initiated a massive clampdown on the entire movement too, in fact. Overnight, possessing Gülen’s books at home, having an account with Bank Asya (founded by Gülenists), sending your children to a Gülenist school, or working at a Gülen-affiliated institution became evidence of membership in or association with the so-called Gülenist Terror Organisation (Fethullahçı Terör Örgütü, FETÖ). Since July 2016, around 125,000 public sector workers have been dismissed by emergency decree. According to an official statement in March 2019, 511,000 people have been detained while some 30,947 are currently in prison on Gülenist-related terror charges (Takvim 2019). As an exemplary case of transnational repression, the Turkish state has additionally strived to take down GM networks worldwide, and has successfully pressured countries from Venezuela to Senegal to Malaysia to close Gülenist schools and deport the movement’s followers. In light of this defeat, the movement is seeking to revive itself by forming a diaspora in democratic European countries – which provide a relative degree of protection beyond the Turkish state’s reach. Now at a critical juncture in its existence, the GM must decide how to restructure itself in this new context.

Jamaah and Politics

Despite all the ruptures and interventions, one thing has remained the same in Turkish politics for decades now: the centrality of the paternal state immersing itself in every aspect of citizens’ lives. Consequently, exclusive control of the state apparatus has been a key target for any political project across all ideological stripes. For many groups, the only way to protect themselves from the state has been to capture it. In particular, the ethnic and religious filters of the Kemalist regime – prioritising the ethnic Turkish, Sunni, and secular – catalysed the infiltration of the excluded groups into the fabric of state bureaucracy.

The main strategy of Islamist actors, beside the National Outlook’s (Milli Görüş) path of forming political parties, was to exploit their clientelistic connections to the centre-right parties and gain benefits and position in return for their electoral support. An ironic example of this is Arif Ahmet Denizolgun, the then leader of the Islamic community Süleymancılar. He served as minister of transportation in the government formed after 1997’s “postmodern coup,” when the military forced the National Outlook’s Welfare Party (Refah Partisi) to step down.

The GM’s calculation was different. Unlike the populism of the National Outlook in trying to reach out to the wider public, the Gülenists adopted a non-partisan and elitist strategy to raise well-educated cadres for the state bureaucracy. In the Turkish polity, which draws a clear line between government and state, these cadres would be the real agents preparing and implementing public policies, no matter who runs the government (Laçiner 2012: 22). Gülen’s motto “build schools, not mosques,” much adored by the Kemalists at the time, rested on this aspiration to cultivate the required human resources and eventually return the state to its owners – the pious Anatolian people. In this endeavour, the Gülenists steadily pursued dissemblance, concealing their faith and affiliation in the face of – also later even in the face of a lack of – military pressure. The movement gained a stronghold particularly among the police force, which the then Turkish political leader Turgut Özal (1983–1993) wanted to strengthen as a counterweight to the secularist military, and therefore staffed with nationalist and religious officers. In time, this security clique within the GM would eclipse the larger civilian organisation in internal decision-making mechanisms.

Also known as “the jamaah,” the GM indeed organisationally fits into this common form of religious community that originally emerged in the aftermath of the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924. Later, jamaahs would be moulded largely by the conditions of the Cold War. While globally favoured as a buttress against communist expansion, they – mostly under secularist suppression – established small informal groups called halaqa (“circle”) or usrah (“family”) – ışık ev (“lighthouse”) in the specific case of GM – to recruit and train followers. Based on a communitarian understanding and hierarchical structure, jamaahs were not meant to deliver intellectual dynamism but have been deliberately practice-oriented – aiming to Islamise the state and society.

Increasing globalisation and waves of political and economic liberalisation in the post–Cold War era brought new opportunities for the jamaahs. Many, including the GM, softened their traditional anti-Western and anti-Semitic rhetoric, and came to accept – strategically or otherwise – democratic values, opting for greater institutionalisation and formalisation within the existing political system. Nevertheless, by not fully abandoning their old covert practices and organisations in the face of the supposed ongoing threat, most jamaahs in the 1990s ended up with dual structures: a largely informal network on one side and its formal institutions, such as charitable foundations or a political party, on the other. The GM formalised most of its activities, especially financial flows, during the military intervention of 1997, while keeping its informal grass-roots activities and networks within the public bureaucracy. The threatening political environment and the GM’s growing power, nullifying the need for reform, seem to have blocked any significant transformation of the movement in the meantime. In the early years of the new century, the GM turned into an archipelago of formal and informal institutions also containing incoherent discourses – which made it difficult even for its members to define the movement’s precise structure. As a result, alternative self-definitions in place of jamaah – such as cemiyet (“society”), hizmet (“service”), or gönüllüler hareketi (“volunteers’ movement”) – were put into circulation.

A Gülenist Diaspora in the Making

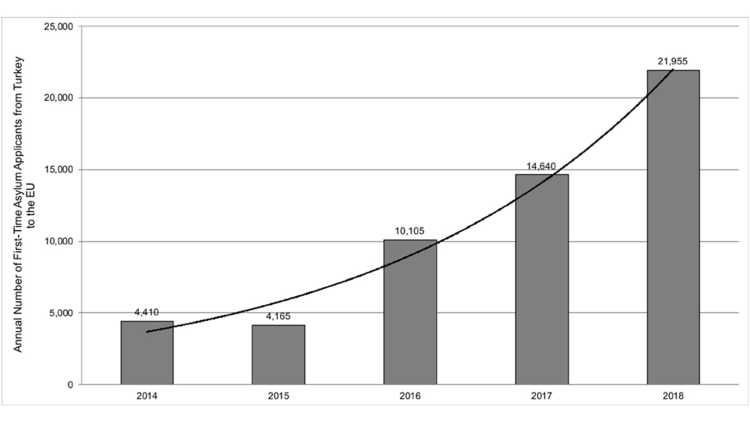

Since the 2013 Gezi Park protests, Erdoğan’s “New Turkey” has prompted a steady outflow of the secular, educated, urban class and underpinned the ensuing flight of capital and talent. The sweeping post-coup crackdown after July 2016 only escalated this process, leading to thousands of Gülenists fleeing at any cost. Since the Turkish government revoked the passports of at least 234,000 people and condemned them to “civil death,” the only exit route remains what Syrian migrants have long endured: a dangerous journey across the Aegean Sea or the Evros River, on the Turkey–Greece border, by boat. According to Eurostat figures, the number of first-time asylum seekers from Turkey has hit new highs and increased five-fold in the European Union, from 4,165 such applications in 2015 to 21,955 in 2018 – leading to a total of 42,530 applications since the 15 July 2016 abortive coup (Figure 1 below). The majority of applicants are followers of the GM (Gall 2019).

With this ongoing inflow of asylum seekers, a Gülenist diaspora is now in the making. In fact, the GM became a transnational network spread over 160 countries. However, that transnational mobility was all on a voluntary basis and, on many occasions, came with the support of the Turkish state authorities. However, the post–15 July 2016 crackdown has added an exilic status, which is for the Gülenists – unlike for the Kurdish movement – a new phenomenon to deal with. Moreover, the persecution cut off the movement’s financial resources in Turkey, which used to subsidy a large portion of its overseas activities. According to a Turkish National Security Council (MGK) report dated July 2017, the state confiscated USD 15 billion worth of assets (including nearly a thousand firms) affiliated with the GM (Müderrisoğlu 2017). With a greatly reduced cash flow and the new burden of sustaining its members in a grim situation, the GM ceased many of its transnational operations and opted to significantly downsize institutionally.

Beyond such political and economic barriers, fleeing Turkey does not guarantee Gülenists finding a safe home. Ankara’s policies of intimidating and purging Gülenists abroad range from seizing passports to abducting suspects overseas. Since July 2016, Turkish pressure has led to the extradition of 107 suspects from countries such as Angola, Malaysia, and Pakistan (Karadağ 2019). Turkey has also confiscated and handed over many Gülenist overseas schools to the Maarif Foundation – which, in this way, has come to run 164 schools and two universities across 55 countries in the just two years since its founding by the government, in 2016 (Canbolat 2018). Besides such blatant measures of repression, the Turkish state is also actively engaged in extensive espionage on its GM enemies.

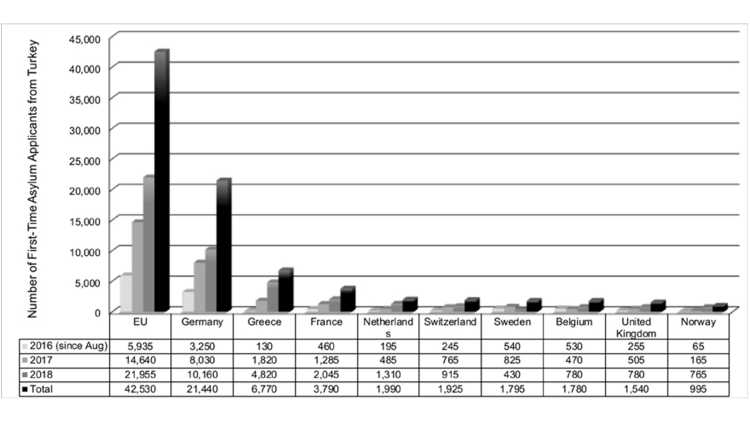

Although the GM has heavily invested in the Global South, the global reach of the crackdown impelled the movement to head towards Western democratic countries, where the rule of law may still provide a shield against the intimidation of the Turkish government. Most Gülenists seeking refuge have ended up in European countries because of their geographical proximity to Turkey. Germany, with a total of 21,440 first-time applicants since July 2016, is leading the list of EU countries from which Turkey citizens seek asylum most. Greece comes second, with 6,770 applicants (Figure 2). It is no surprise, then, that the Gülenists see Germany as their “new hub” (Köhne and Siefert 2018).

Compared to other Turkish Islamic movements, the GM is a latecomer in Europe. Beginning to institutionalise only in the mid-1990s, it built up a vast network of schools, tutoring centres, and media outlets in a short space of time. After July 2016, however, the movement’s support base in Germany shrank from 100,000–150,000 to 60,000–80,000 people (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017), three schools were shut down, and the number of tutoring centres dropped from 110 to 76 (Karakoyun 2018: 36). Conversely, due to the incoming asylum seekers, new integration and child care centres are now being planned by the movement.

With the refugee influx to Europe, an intra-community divide has emerged within the GM between established locals and newcomers. Traditionally, the local Gülenist communities in Europe are less educated and rely on small ventures alone. In contrast, the newcomers – consisting of exiled teachers, engineers, doctors, journalists, and businessmen – are better-educated and professionally more successful. However, with the newcomers lacking the financial resources needed as part of the asylum process, recent GM activities have been subsidised by the locals – giving them the upper hand so far. Another divide arises from the generational gap within the movement. While the older generations carry the memory of earlier persecutions and maintain a more conservative, resilient approach to the routes GM can and indeed should take, the younger one – having a globally better-integrated background – feels freer to challenge the decision-makers within the movement.

Winds of Change?

While the GM is trying to nurse its heavy wounds in a diasporic context, its abrupt downfall has sparked a heated intra-community debate on what exactly went wrong. Exile was not just a harsh winter for the movement, but, indeed, an existential crisis that let many followers to embark on extensive soul-searching. Amid all the radical changes and intensifying tragedies after July 2016, the community culture of reifying secrecy – as prompted by the Turkish proverb “Kol kırılır yen içinde kalır” [“The broken arm stays inside the sleeve”] – shattered considerably. For the first time ever, criticisms from within the movement have been raised out loud.

Critical voices, having almost no influence on the decision-making mechanisms but growing resonance with the membership base, have been challenging the practices and orthodoxies of the movement via online platforms such as Maviyorum [www.maviyorum.com], Kıtalararası [www.kitalararasi.com], or The Circle [www.thecrcl.ca]. On these platforms, while some call to outright disestablish the movement and its administration, others differentiate between hizmet as a set of principles and ideas and cemaat as the organised body – and thus demand the reformation of the latter. Criticisms of the organisational structure of the GM usually call for localisation, bottom-up administration, transparent decision-making mechanisms, disassociating the movement from the state bureaucracy, a non-partisan stance, abandoning Turkey-centred and Machiavellian strategies, and demand the overcoming of the lack of coherence between discourse and practice – nurturing, as it does, mistrust of the movement. Ideational criticisms cite the understanding of “chosen-ness” and ruling with a divine mandate, the infallibility of the leader, fatalism, and the self-approving theological understanding – which together prevent internal critique. While most of the latter criticisms go in parallel with the global reformist winds blowing through general public debates on Islam, Gülen himself comes from the traditional school and firmly lies within the orthodox Turkish Islam tradition – making compromise difficult on this front.

Reading these initiatives as the mere debuting of a handful of educated figures would be misleading, since this soul-searching reverberates in part within the social base of the movement too. The flourishing of critical voices after July 2016 relates to several factors. First, the traumatic experience of exile has broken the social contract within the community. Many Gülenists left not only their homes and relatives, but also their community roles and networks in Turkey. Now building a new life in a new environment, they revisit their attachment to the movement; some even open up a new chapter, taking an individual stance. Second, the GM’s inability to develop a solid narrative about what happened on 15 July 2016 and before has culminated in growing discontent. “This too shall pass” rhetoric has been of no comfort to the many trying to make sense of the ongoing events. Third, the lack of internal channels to raise one’s voice led to an outburst of open debate among Gülen followers on social media. Finally, being subject to an extensive purge by a government championing the Islamic faith, the unconditional public support for the purge, and now being sheltered by secular Europe have surely generated an emotional break with the Turkish state and society among many Gülenists. This severing was not only with the state and nation, however, but also with religious belief itself, nurturing disenchantment and propelling many followers to revisit their very conceptions of Islam and secularism.

Waiting for the Storm to Pass

So far, the GM has not welcomed the criticisms from within – on the basis that it is going through hard times, and also that priority should be given to supporting the victims of Erdoğan’s regime. To strengthen its sense of purpose, the GM has framed the ongoing ordeal as “the destiny of the road” (yolun kaderi) – pointing out that all the prophets and the faithful have been subject to cruelties at one time or another (Gülen 2019). In a symbolic twist, however, the GM’s flagship magazine, modestly titled Sızıntı (“The Leak”), has been released since 2017 under the new title Çağlayan (“Waterfall”), implying that the recent exodus is a blessing in disguise and will only help the movement expand further in time. While this buoyant acquiescence has a soothing effect on traumatised followers and helps them overcome their excruciating situation, it may also block self-reflection and coming to terms with present realities. Living in denial, many Gülenists in exile retain hope of going back to Turkey one day soon. A widely held assumption among them is that one now only needs to wait until the storm has passed. The movement will simply rise from the ashes once the Turkish masses come to realise the GM’s value in the midst of the country’s political and economic demise under Erdoğan’s rule.

The nascent Gülenist diaspora, as it emerges today, lives in a comfort zone on several levels, diminishing the odds of internal change and reform occurring. First, just being a victim of Erdoğan’s regime suffices for many followers and outside observers to consider the GM in a positive light. Swimming with, if not thriving on, the tide of far-reaching anti-Erdoğan sentiment in Europe, the Gülenists find extensive coverage of the situation in European media – illustrating the scope of the relentless purges of the New Turkey through numerous personal tragedies. For instance, the movement recently curated a mobile exhibition called Tenkil (“Extirpation”) Museum. At some point, however, this victim discourse might lead to compassion fatigue.

Second, the twin pillars of the GM – education and interfaith dialogue – make the movement still appealing to European policymakers and bureaucrats, who have to tackle the question of integration and to prevent the growth of radical Islam. To give just one among many examples, Bruno Kahl, head of the German Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst, BND), despite criticisms about the GM’s opaque structure, defines it as a “civil association for the purpose of religious and secular education” (Knobbe et al. 2017). This second comfort zone – that the movement, for European leaders, is good enough the way it is – makes drastic change in the words and deeds of the Gülenists less possible.

Finally, the overemphasis on the 15 July 2016 abortive coup – a rhetoric that the AKP government actively pursues in order to negate past collaboration with the Gülenists – obscures a significant debate about the practices and goals of the GM in general. Directing the spotlight on the last few years alone, this Turkish government propaganda actually helps the movement sweep earlier wrongdoings under the carpet and even save face – if it can disentangle from the still mysterious 15 July 2016 events one way or another.

The Trajectories of the Gülenist Diaspora

In between the push for profound change, on the one hand, and the GM’s comfort zones and overall strategy to rally around the flag, on the other, there is seemingly still room for shared acknowledgements. A good example is the critical report by Ahmet Dönmez, a former correspondent of the Gülenist daily Zaman, who wrote about the dark side of the movement: namely, allegations of the continuing ascendancy of the Turkish intelligence services within the GM’s ranks and an aborted plot to incite a Gülenist prison riot (2018). The publication of the report impelled the Alliance for Shared Values (AfSV), the GM’s official representative in the US, to release a statement on its website that confirmed the existence of this plot and that reiterated the movement’s adherence to the rule of law and ethical principles (2018). This testifies to a considerable sea change for a movement that was long known for intimidating anti-Gülenist journalists, but has now come to show some transparency in confirming the validity of this critical report by its former employee.

Beyond the GM’s (in)capacity to make compromises, post-2016 conditions push the movement in a certain direction too. One is transparency. The raison d’être of all the dissemblance and covert activities was the assumed secular threat. Now, in the liberal environment of Europe, the movement has no excuse to replicate a similar set-up. With this awareness, the GM’s umbrella organisation “Voices in Britain” has stepped up the transparency initiative in the United Kingdom and formalised its previously opaque grass-roots institutions such as religious meetings (sohbet) and constituency-based networking (bölgecilik) under the Sohbet Society and Mentor Wise, respectively – this to “achieve complete coherence between its inner and outer workings” (2018: 11). Likewise, the Forum Dialog in Germany now abides by the Transparent Civil Society Initiative (Initiative Transparente Zivilgesellschaft). How far this transparency will ultimately be pursued is yet to be seen.

Besides transparency, the old habit of Gülenists to subdue their faith and promote a secular and non-denominational discourse also needs to be revisited in the European context. If the GM aims to take on a role against Islamist radicalism and Islamophobia in Europe and the US, that will require the movement to be more outspoken in debates about Islam – and to engage more with other Muslim diasporic communities in these regions too (Keleş et al. 2019: 269). In practice, while establishing close links to churches for interfaith dialogue, the GM so far has avoided contact with other Muslim communities and was not represented within, for instance, the main German Islamic organisations (Seufert 2014: 25).

In fact, many of the criticisms raised against the GM – statism, chauvinism, favouritism, leader-centredness, hypocrisy, dogmatism, and an acute lack of self-reflection – refer to the common pathologies of Turkey’s toxic political culture that also ensnare other movements, Islamic or not, in the country too. Yet its “strategic ambiguity” and the lack of transparency in its goals, which led to the GM’s both rise and eventual fall, turn the movement into an unreliable political figure. Its over-politicisation and reluctance to come to terms with past misdeeds eclipse the ongoing tragedies affecting tens of thousands of ordinary followers. The movement may keep its ideational and organisational structure and remain as a religious community on the periphery, both exiled and disempowered. Without true self-reflection and full transparency, it seems impossible for the GM to ever gain a meaningful hold in Europe. Beyond these future trajectories, the movement still heavily relies on the “charismatic authority” of its leader – hence, there remains also the question of what a post-Gülen era will look like.

Facing the influx of Gülenist asylum seekers, European authorities developed new instructions to assess the risk of persecution before granting asylum to this specific stream of applicants (EMN 2017). Despite the cynical attitude towards the GM in general, its classification by the Turkish state as a terror organisation has not found adherents in the West. In March 2019, US First Lady Melania Trump visited a Gülen-affiliated charter school, the Dove School of Discovery, which the White House described as an “award-winning elementary school that focuses on incorporating character education throughout its curriculum” (2019). Likewise, the German federal government recently funded a large project that the Gülenists joined in with – Berlin’s “House of One,” where Christians, Muslims, and Jews can worship under the same roof (Köhne and Siefert 2018). Moreover, some overseas Gülenist schools, for instance in Ethiopia, were transferred to Gülen-affiliated businessmen with German citizenship in order to protect them from potential aggression by the Turkish state (İnat et al. 2018).

Considering the ongoing inflow of Gülenists as well as of other oppositional groups from Turkey, European and German decision-makers have the power to affect – if not shape – the trajectories that the Gülen Movement can potentially take. The movement should be pushed for full financial and organisational transparency in its new diasporic form. Moreover, by sheltering the bulk of the Gülenists, European countries have now imported an additional Turkey-originating conflict after the Turkish–Kurdish one. In order to overcome the deepening of these fault lines and the ghettoisation of such diasporic groups, European leaders could create platforms bringing diverse Turkish/Kurdish actors together – something that is impossible in Turkey at the moment.

Europe now hosts a diverse array of politically persecuted identity groups, who live isolated from each other not only in deeply polarised Turkey but also now in diaspora too. Policymakers should aim to establish channels between these exiled groups, and sow the seeds for a new social contract in Turkey eventually emerging. More specifically, dialogue conferences and different workshops should be organised in which these exiled actors can face and confront each other – and eventually discover ways to reconcile their conflicting realities. Such a participatory and inclusive process in diaspora, acknowledging the grievances of all groups, may in the long term inspire Turkey to move from a divided past and present to a shared future.

Although the post-coup crackdown (Turkey arresting 50 German nationals, Germany “harbouring” Gülenists) put further strain on their already damaged bilateral relations, both countries still have a keen interest in building bridges: Turkey needs Germany’s political and economic support, while the latter wants to avoid a further mass influx of Syrian migrants. Notwithstanding this, as EU and German leaders do not want to see the Turkish economy in utter ruin and have concerns that an unstable Turkey may cause millions more to eventually flee, contributing to Turkey’s future will work better than the appeasement policies pursued so far.

Footnotes

References

Alliance for Shared Values (2018), Statement of the Alliance for Shared Values on the Principles of the Hizmet Movement, 27 November, https://afsv.org/alliance-for-shared-values-statement-on-principles-of-the-hizmet-movement/ (2 May 2019).

Canbolat, Tülay (2018), Maarif Vakfı 55 ülkeye ulaştı, in: Sabah, 21 October.

Dönmez, Ahmet (2018), “Cezaevlerini Kana Bulayacak Isyan Planı Son Anda Önlendi” Iddiası, in: Patreon, 9 November, www.patreon.com/posts/cezaevlerini-son-22616584 (2 May 2019).

Düzel, Neşe (2011), Şerif Mardin: Gülen’in stratejisini bilmiyoruz, in: Taraf, 11 October. EMN (European Migration Network) (2017), EMN Ad-Hoc Query on Claims from Turkish asylum seekers, 25 April, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/2017.1172_no_claims_from_turkish_asylum_seekers.pdf (2 May 2019).

Eurostat data, http://bit.ly/2vK3gWI (2 May 2019).

Gall, Carlotta (2019), Spurning Erdogan’s Vision, Turks Leave in Droves, Draining Money and Talent, in: The New York Times, 2 January.

Gülen, Fethullah (2019), Bamteli: Yangın, İmtihan ve Yardım, Herkul, 6 January, www.herkul.org/bamteli/bamteli-yangin-imtihan-ve-yardim/ (2 May 2019).

İnat, Kemal et al. (2018), Almanya’da FETÖ Yapılanması ve Almanya’nın FETÖ Politikası, Ankara: SETA.

Karadağ, Kemal (2019), 107 FETO fugitives brought back to Turkey so far, AA, 27 March, www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/107-feto-fugitives-brought-back-to-turkey-so-far/1431325 (2 May 2019).

Karakoyun, Ercan (2018), Egal wo ihr seid, wir finden euch! – Erdoğan (Bericht über die Verfolgung der Gülen-Bewegung), Berlin: Stiftung Dialog und Bildung.

Keleş, Özcan, İsmail Mesut Sezgin, and İhsan Yilmaz (2019), Tackling the Twin Threats of Islamophobia and Puritanical Islamist Extremism: Case Study of the Hizmet Movement, in: Esposito, John L., and Derya Iner (eds.), Islamophobia and Radicalization, Cham: Springer, 265–283.

Knobbe, Martin, Schmid, Fidelius, and Alfred Weinzierl (2017), BND zweifelt an Gülens Verantwortung für Putschversuch, in: Spiegel Online, 18 March, www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/tuerkei-putschversuch-laut-bnd-chef-wohl-nur-vorwand-fuer-radikalen-kurs-erdogans-a-1139271.html (2 May 2019).

Köhne, Gunnar, and Volker Siefert (2018), Die Gülen-Bewegung: Neues Zentrum “Almanya,” in: Deutsche Welle, 13 July, www.dw.com/de/die-gülen-bewegung-neues-zentrum-almanya/a-44645120 (2 May 2019).

Laçiner, Ömer (2012), Cemaat-Siyaset, Birikim, 282, 19-25.

Müderrisoğlu, Okan (2017), FETÖ’nün 48 milyarı devletin kasasında, in: Sabah, 19 July.

Seufert, Günter (2014), Is the Fethullah Gülen Movement Overstreching Itself? A Turkish Religious Community as a National and International Player, Berlin: SWP.

Süddeutsche Zeitung (2017), Türkei: Mehr als 1000 Festnahmen, 31 July.

Takvim (2019), Hükümetten FETÖ açıklaması: 15 Temmuz 2016'dan bu yana 511 bin kişi, 10 March.

The White House (2019), First Lady Melania Trump to Travel on a Three-State Tour to Promote Be Best, 28 February, www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/first-lady-melania-trump-travel-three-state-tour-promote-best/ (2 May 2019).

Voices in Britain (2018), British Hizmet on Identity-Based Transparency, Green Paper, 1, www.voicesinbritain.org/assets/docs/green-papers/Green-Paper-01-British-Hizmet-on-Identity-Based-Transparency.pdf (2 May 2019).

Watmough, Simon P., and Ahmet Erdi Öztürk (2018), The Future of the Gülen Movement in Transnational Political Exile: Introduction to the Special Issue, in: Politics, Religion & Ideology, 19, 1, 1-10.

Zaman, Amberin (2019), Families Fret as Turkey’s Gulenist Purge Continues, Al Monitor, 19 February, www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/02/accused-gulenist-teachers-disappear-arrest.html (2 May 2019).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Hakkı Taş (2019), The Gülenists in Exile: Reviving the Movement as a Diaspora, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-62741-3

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.